Apple and the Innovator’s Dilemma

Apple and the Innovator’s Dilemma

This paper was originally written in 2010 for a Corporate Innovation class at Kellogg; please forgive any formatting errors carried over in the conversion from PDF, as well as the excessive footnotes!

Apple’s unbroken string of success seems to suggest it is impervious to the Innovator’s Dilemma. Why has it been so successful, and can it be replicated?

Beginning with the introduction of the iPod in 2001, Apple has had an uninterrupted string of success in the consumer electronics segment. That success has, in turn, driven an increase in revenue of 1,116% and net income of $14 billion in 2010 compared to a loss of $25 million in 2000. 1

This uninterrupted success is quite remarkable in technology, which considers upheaval a matter of course. For example, in the PC industry, IBM pioneered the segment, and was surpassed by Compaqʼs low-cost model. Then, Compaq was surpassed by Dell and its direct sales model. Now Dell has been passed by HP with its superior retail channels. HP itself is strongly threatened by Acer and other Asian manufacturers. Another example is the Internet: AOL gave way to Yahoo!, which in turn has given way to Google.

The Innovator’s Dilemma

In their groundbreaking article “Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave,” Joseph Bower and Clayton Christensen gave a classic example of this sort of upheaval in the hard drive industry. Within ten years the hard drive industry moved from the 14-inch drives that had been used in mainframes to 8-inch, then 5.25-inch, then 3.5- inch drives. 2

Each time a disruptive technology emerged, between one-half and two-thirds of the established manufacturers failed to introduce models employing the new architecture…Three waves of entrant companies led these revolutions; they first captured the new markets and then dethroned the leading companies in the mainstream markets. 3

According to Bower and Christensen, the reason this sort of disruption occurs is because “companies listened to their customers, gave them the product performance they were looking for, and, in the end, were hurt by the very technologies their customers led them to ignore.” 4

Moreover, this sort of disruption is, according to Bower and Christensen, endemic to well-run companies.

Using the rational, analytical investment processes that most well-managed companies have developed, it is nearly impossible to build a cogent case for diverting resources from known customer needs in established markets to markets and customers that seem insignificant or do not yet exist. 5

Low-End Disruption

Christensen and co-author Michael Raynor expounded on the process of low-end disruption in the book “The Innovatorʼs Solution,” highlighting the move from interdependent to modular solutions. In new markets,

Companies must compete by making the best possible products. In the race to do this, firms that build their products around proprietary, interdependent architectures enjoy an important competitive advantage against competitors whose product architectures are modular, because the standardization inherent in modularity takes too many degrees of design freedom away from engineers, and they cannot optimize performance…Companies that compete with proprietary, interdependent architectures must be integrated. 6

However, over the long-run, integrated companies produce a product that is “too good,” and “customers are happy to accept improved products, but theyʼre unwilling to pay a premium price to get them.” 7 Instead customers make decisions on different vectors than performance, such as cost or convenience. This, in turn, favors modularized solutions that allow for increased flexibility and lower cost.

Modularity has a profound impact on industry structure because it enables independent, nonintegrated organizations to sell, buy, and assemble components and subsystems…When that happens, companies can mix and match components from best-of-breed suppliers in order to respond conveniently to the specific needs of individual customers…These nonintegrated competitors disrupt the integrated leader. 8

This is certainly a major aspect of what befell Apple in the 80s and 90s. Apple helped create the personal computer category with the Apple II in 1977, and seven years later launched the Macintosh and its revolutionary graphical user interface. 9 However, the Macintosh was simultaneously too advanced and too limited for the corporate IT departments that were the primary customers for computers in the 1980s. More attractive were IBM and IBM-compatible PCs that provided good-enough performance with a lower price that reflected their commoditized nature. As time went on the features offered by the Macintosh were not enough to justify its ever- increasing price premium over computers running Windows on Intel chips, and Apple in 1997 tottered near bankruptcy. 10

Christensen and Raynor recounted this classic tale of disruption in The Innovatorʼs Solution:

During the early years, Apple Computer — the most integrated company with a proprietary architecture — made by far the best desktop computers. They were easier to use and crashed much less often than computers of modular construction. Ultimately, when the functionality of desktop machines became good enough, IBMʼs modular, open-standard architecture became dominant. Appleʼs proprietary architecture, which in the not-good- enough circumstances was a competitive strength, became a competitive liability in the more-than-good-enough circumstance. Apple as a consequence was relegated to niche-player status as the growth explosion in personal computers was captured by the nonintegrated providers of modular machines. 11

The iPod Exception

The turnaround fostered since then by Apple’s prodigal founder, Steve Jobs, is well-documented and one of the most amazing business stories of all-time. Jobs’ first few years were spent stabilizing the Mac business, but Apple didnʼt really begin to take off until the launch of the iPod for Windows in October 2003. That year saw an increase in revenue of 33.4% to $8,279 million and a 286% increase in profit to $266 million. 12 Yet that announcement was accompanied by increased certainty among market observers that it would only be a matter of time until Apple faced low-end disruption, just like they did with the Mac:

Forbes — Apple Computer defied expectations and proved a viable business could be built around digital music. And, so far, the company has done better in this arena than anyone else has. But now the copycats are on the march, and in time they’ll have the numbers on their side. If competitive offerings gain market share or an industrywide standard is imposed, Apple would either have to adapt to market realities, making its two-part music offering less special, or leave it unchanged and watch iPod sales–and profits–erode. I’ve heard this story before. I didn’t like how it turned out the first time. 13

Bloomberg — Whatever Apple’s current technological lead, history is not on its side. Although it increased its share of the digital music player market to 66% in August, according to NPD Group Inc., up from 28% the year before, many a tech pioneer has seen its early dominance wither. Just look at Palm in PDAs, Nintendo in game consoles, and Apple itself in PCs. Already, rival music players offer more features at lower prices. “It’s a nascent market, and [Apple’s lead] is not sustainable,” says Dave Fester, general manager of Microsoft’s Windows digital media division. 14

BusinessWeek — It’s ironic that in this moment of triumph for Apple CEO Steve Jobs, the greatest challenge yet to Apple’s online music dominance is emerging. This week, Microsoft announced a marketing campaign designed to exploit iPod’s most obvious weakness. Dubbed “Plays for Sure,” Redmond’s campaign seeks to provide consumers with a guarantee that any audio- or video-playback device labeled with those words will play any content file purchased legitimately from Microsoft or licensees of its Janus digital-rights management (DRM) technology… More than ever, standards matter in the tech world. They’re the only way to ensure universal compatibility — which consumers clearly want — in fragmented markets. While Apple wins accolades for its beautifully designed, tightly integrated products, its insistence on total control could make continued domination of this market much harder… Microsoft will probably make a steady stream of improvements in its media-player software. Will it ever match Apple in ease of use and elegance? No — but who cares, really? Many consumers are more than happy with something that’s good enough, and cheap. 15

“Many consumers are more than happy with something thatʼs good enough, and cheap.” Or, to put it in technical terms, many consumers are more than happy with low-end disruptors.

Yet, those low-end disruptors never actually disrupted the iPod. 16

In fact, the iPodʼs long run at the top seemed, well, impossible. That was the word used by Gene Munster, a Piper Jaffray analyst. “Nobody can sustain an 80 percent market share in a consumer electronics business for more than two or three years. It’s pretty much impossible.” 17

So how did the iPod accomplish the impossible and avoid low-end disruption? While it is true that powerful branding that established the iPod as a must-have status symbol played a role, there were also important strategic moves Apple made to counteract low-end disruption. Moreover, Apple is following the same strategy with the iPhone and iPad, and while it is still too early in the smartphone and tablet industries to draw any firm conclusions about their long-term success, the iPodʼs history certainly portends well. This article will examine those strategies (using examples from the iPod, iPhone and iPad) through the framework provided by Christensenʼs model.

What Apple Does to Escape Disruption

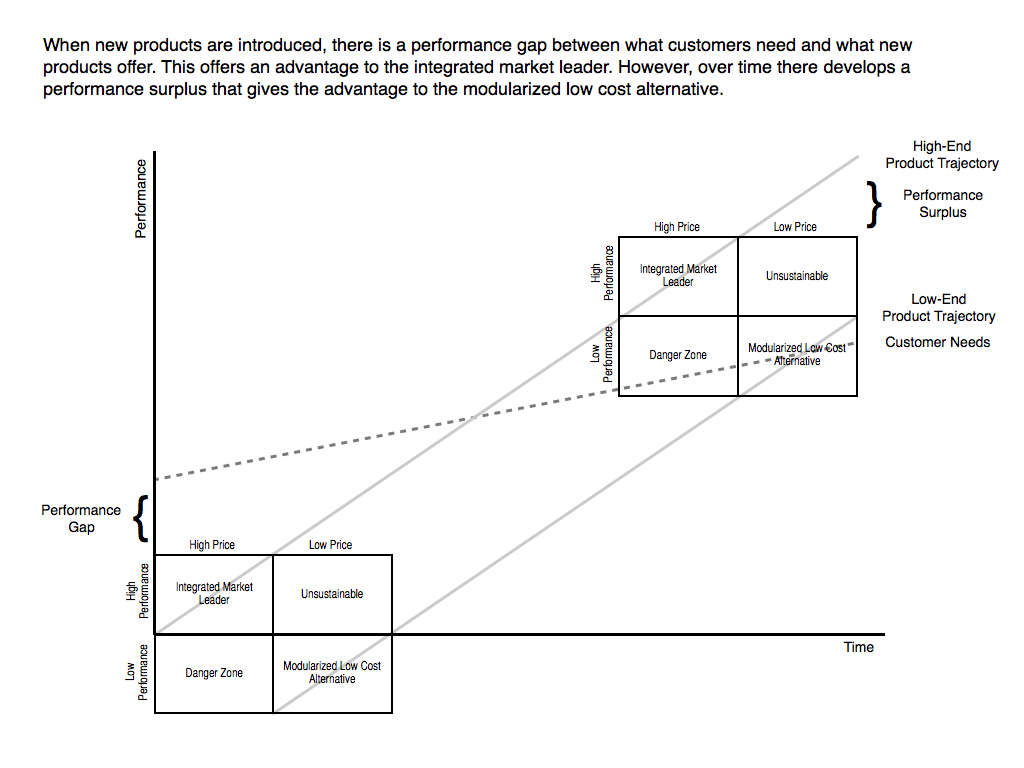

In that model of low end disruption, there are several disparate factors at play (Figure 2).

- The initial differentiation

- The product trajectory

- Customer needs

- Price

The majority of innovators tend to focus exclusively on their differentiation, and milk that advantage for as long as possible. Apple, on the other hand, manipulates all four factors, putting off the threat posed by the Innovator’s Dilemma. And then they pull off the ultimate escape act: disrupting themselves.

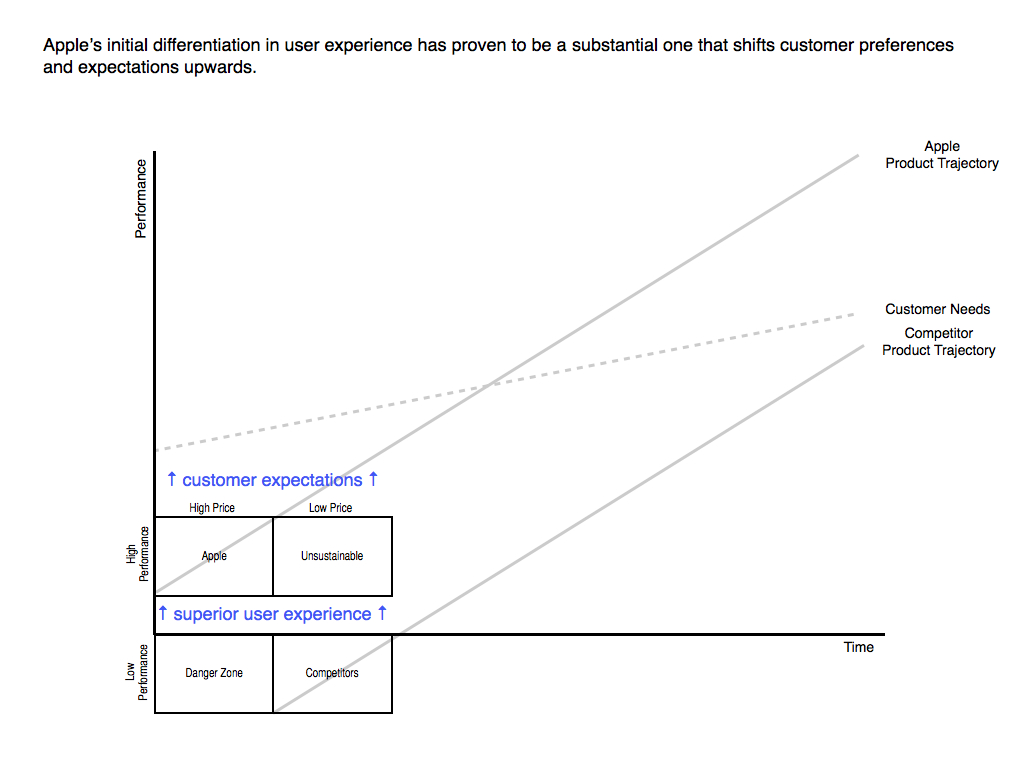

The Initial Differentiation

Apple’s primary means of differentiation has remained remarkably consistent ever since the first Macintosh — their products have a superior user experience. While the factors that go into this advantage are many, it has proven remarkably difficult to copy. Consider the Macintosh: Microsoft-powered computers enjoyed an advantage in performance and features from the very beginning, yet the Macintosh remained an extremely profitable product for over ten years for no other reason than its ease-of-use. It was only until Windows 95 that the Windows user- experience became “good enough” to lead Macintosh customers to abandon the platform for Windows computers that were superior in every other way.

Apple’s has maintained its user experience differentiation via innovative user interfaces with its other breakthrough products. For example, the iPod introduced the click wheel and the iPhone multitouch. However, Apple has actually expanded its user experience advantage, primarily through iTunes. Prior to the iPod, the only way to add music to an MP3 player device was to ʻmountʼ the device to your computer, and copy files over manually. All organization had to be done by hand through folders and naming conventions, and file operations could be done on the device itself. 18 In the case of the iPod, however, iTunes on your computer completely managed the music. All a user needed to do was plug in their iPod. In this respect the iPod and its user experience are best viewed as an entire system, not just standalone devices (a situation that is also the case with the iPhone and iPad).

The utility and user experience of the iTunes/ iPod system was greatly expanded with the addition of services, primarily the iTunes Store. The iTunes Music Store has had several beneficial effects on the user experience in its original incarnation that accompanied the iPod. First, it greatly simplified the experience of acquiring digital music, but more importantly, it also legitimized it. Second, it created an expectation in customers for a store that would accompany the player; however, creating a store requires much more than a bit of code or industrial design. It requires contracts with record labels, bandwidth capacity, etc., all of which makes replicating the entire experience significantly more difficult. Third, at least for the first six years of its existence, the store also provided a lock-in via Appleʼs proprietary Fairplay DRM. 19 The more songs a customer bought through the iTunes Music Store (the Music part of the name was dropped in 2006) the more likely they were to buy another iPod. 20

The iTunes App Store has had an even more transformative effect on the iPhone user experience. First, it transformed the iPhone into a platform capable of an infinite number of use cases. Second, it introduced a network effect similar to the one previously enjoyed by Windows: the more people who own iPhone, the more developers want to write apps for the platform, which attracts more users, and on and on it goes. Third, the fact that the app store is also housed in iTunes means the payment system is remarkably easy; more importantly, it means that most potential customers have already put in their credit card number, a significant hurdle for any other competing platform (iTunes currently has 160 million credit card numbers). 21

The iPad has incorporated all of these advantages in the user experience to pioneer a new category that in many respects depends on a superior user experience to be worthwhile. A tablet is severely limited in comparison to a computer when it comes to features, and to a phone when it comes to mobility. The only reason for a tablet device to exist is if it delivers a superior user experience, and while few competitors to the iPad have yet to appear, it seems likely that Apple’s initial differentiation will be the largest yet.

The Product Trajectory

Apple’s focus on user experience as a differentiator has significant strategic implications as well, particularly in the context of the Innovator’s Dilemma: namely, it is impossible for a user experience to be too good. Competitors can only hope to match or surpass the original product when it comes to the user experience; the original product will never overshoot (has anyone turned to an “inferior” product because the better one was too enjoyable?). There is no better example than the original Macintosh, which maintained relevance only because of a superior user experience. It was only when Windows 95 was “good enough” that the Macintosh’s plummet began in earnest. This in some respects completely exempts Apple from the product trajectory trap, at least when it comes to their prime differentiation.

However, even when you consider other more traditional features, Apple has demonstrated a remarkable level of restraint. This especially has been the case in version 1.0 products. For example, the original iPod lacked the more common USB connection standard, and more critically, did not work on Windows. The original iPhone lacked features such as copy-and-paste, 3G connectivity, and multitasking. The iPad does not have a camera and also lacked multitasking.

The net result of these omissions is that Appleʼs version 1.0 product often falls significantly below the consumer preference line for traditional features, meaning that adding features is more likely to bring the product up to the consumer preference line (as opposed to extending above it). Moreover, those features are added relatively sparingly, reducing the slope of the product trajectory line.

This creates a fascinating dynamic vis a vis the competition. The reason Apple can successfully launch products that lack seemingly critical features is because of the intense focus on the user experience; however, competitors usually view the lack of features as an opportunity and quickly launch products that seem similar but with better features. However, they rarely if ever match the Apple user experience and usually fail to compete successfully. Therefore competitors quickly iterate and launch new products with more features. This results in the competitorsʼ products quickly overwhelming customers with features — the path supposedly reserved for the innovator! In this respect, it is the followers who fall prey to the Innovator’s Dilemma.

Customer Needs

As a category creator, Apple’s first advantage is the ability to shape consumer expectations. For example, the iPod created the expectation that music transfer to a portable player be completely seamless, and introduced the patented click wheel. The iPhone defined the form factor and interaction paradigm for future Internet-focused smartphones, and created the concept of an app store. These efforts defined the direction of customer needs in a way that favored Apple.

Secondly, Apple’s product introductions and advertising increase the customer needs slope to more closely match the trajectory of Apple’s products. An excellent example is Apple’s recent introduction of Facetime, the video calling capability for iPhone 4 (later expanded to iPod Touches and Mac OS X). Several competing phones, such as Nokia smartphones, had video calling capability for years, but it was yet another feature that customers didn’t want and didn’t use — i.e. a feature that contributed to the Innovator’s Dilemma. However, when Steve Jobs introduced the feature during a keynote address in June, 2010, it was a full demonstration of the capability with a massive press audience. Apple then launched an advertising campaign centered on Facetime that levered up the emotional attachment to the product. The net result was that Facetime became a must-have feature that drove purchases and is forcing competitors to respond. 22

Third, Apple’s retail stores further increase the customer needs trajectory. All of Apple’s products are available for unfettered use in the retail stores, and retail associates willingly spend time demonstrating the capabilities of all of Apple’s products. Continuing with the Facetime example, Apple created a special toll-free number that store visitors could call to try out Facetime from the retail stores, demonstrating the feature and creating demand. The stores also offer trainings and workshops that not only improve the user experience of buying an Apple product, but also ensure that customer’s are exposed to and demand all of the features in a given Apple product. The net effect is that even from a feature perspective Apple products are much less likely to outstrip customer needs; moreover, competitors have no choice but to match every feature, but without the customer service and ease-of-use of Apple, which creates unwieldy products.

Price

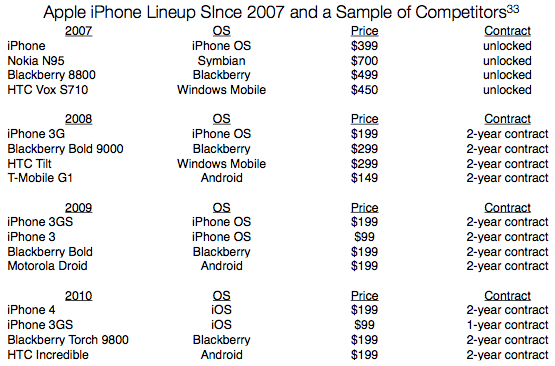

Sustainable differentiation and increased consumer preference trajectories suggest higher prices and an opportunity for competitors to be low-cost competitors. Yet the evidence suggests this hasnʼt happened.

The original iPod launched in 2001 at a price point of $399 for 5 GB of storage. Its primary competitor was the Creative Nomad Jukebox which had 20 GB of storage, although it was significantly larger and more difficult to use. It also cost $399 23

The iPod did not face a large number of similar specced competitors until late 2004. However, even then the price remained quite competitive.

By 2004, Apple was also showing its willingness to cover as many price points as possible, offering products from $249 to $599. By 2007, the lineup had extended in both directions, and while competitors had for the most part standardized on the same capacity as the iPods, they werenʼt necessarily less expensive.

The iPhone is similarly competitive, primarily due to the unique nature of the wireless industry where most phones are subsidized and customers have to agree to two-year contracts. 30 Moreover, phones often decline in price over their lifespan in response to consumer demand (or lack thereof).

However, the iPhone has consistently been very competitive and should be going forward as the industry has standardized on a price of $199 for smartphone with a two-year contract. According to CNNMoney, 31

On the four major wireless networks…there are 13 smartphones priced at $199 with a two-year contract. There are no phone models with a higher starting price (add-ons like more memory can increase the price tag), and there are more smartphones selling at $199 than at any other single price point.

Price references 32

One reason Apple has been able to remain so price competitive is by securing its flash memory supply, a key component in the iPod Nano, Shuffle, Touch, iPhone and iPad. In 2005, Apple reached five-year agreements with multiple memory vendors to secure its supply at favorable prices through 2010 and foreclose competitors. 33 In addition, Apple has benefitted from tremendous economies of scale befitting its dominant position in the market. While the tablet market is still nascent, it appears that Apple has priced the iPad very competitively as well. The entry level iPad, with a 9” screen and Wi-Fi networking retails for $499, $629 with cellular networking. The only comparable product on the market, the Samsung Galaxy Tab, has only a 7” screen, and retails for $600 with cellular networking.

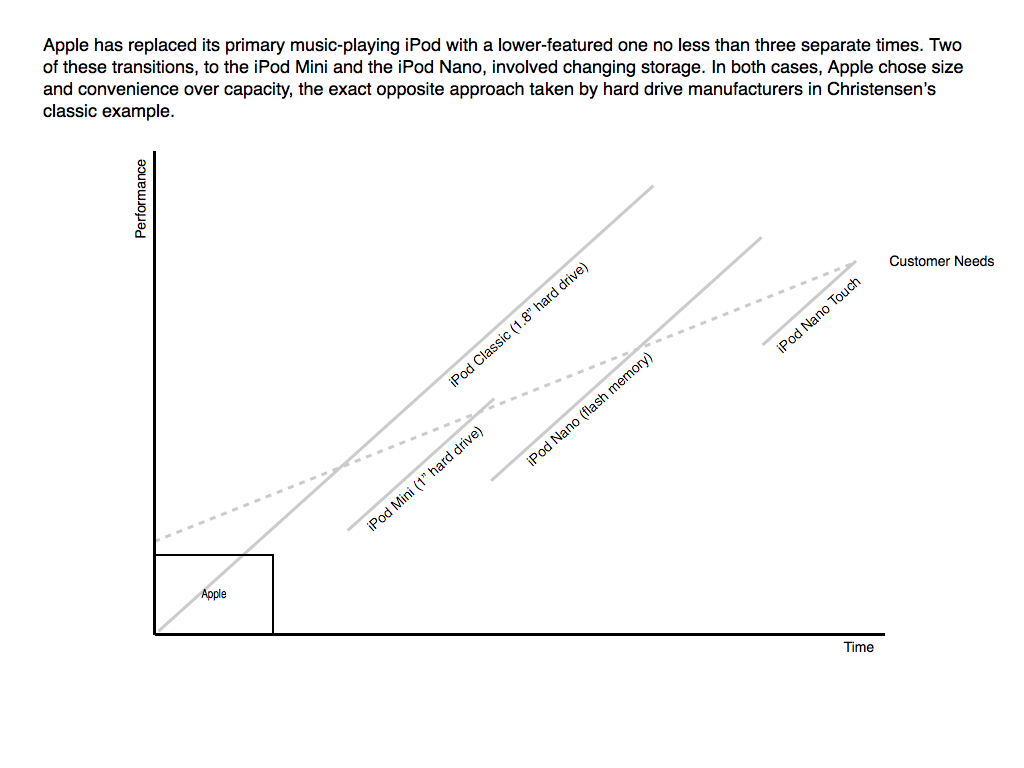

Self-Disruption In the MP3 Player Market

By enhancing the iPodʼs initial differentiation, focusing product improvements on the user experience and high-value features, educating customers and staying competitive on price, Apple in many ways forestalled or downright reversed the Innovatorʼs Dilemma in the MP3 Player market. However, itʼs important to note that they also had the discipline to disrupt themselves.

Twice Apple introduced new models of the iPod that had smaller storage and new price points. In the case of the iPod Mini, Apple introduced a smaller 4 GB model based on a 1” hard drive and priced it at $249. Pundits were stunned, for a regular iPod with 15 GB of memory could be had for only $50 more. Alex Salkever of BusinessWeek, who had previously predicted the iPodʼs disruption above, wrote:

Less music in a device marginally smaller at about the same price. Get it? I didn’t, and few others will, either. In fact, while I was watching Jobs give his spiel, my mind replayed the infamous scene from the cult classic mockumentary Spinal Tap where the dim rock band tries to explain that dials on their amplifiers go to 11 — and that’s what makes them louder. I was left with the same sense of befuddlement after watching Jobs show off the smaller but much wimpier miniPod. 34

Yet the iPod Mini became a massive success, for many of the same reasons smaller size hard drives had years before in Christensenʼs classic example: it was smaller, more convenient, and cheaper. In fact, the iPod Mini became Appleʼs best-selling iPod. 35

And then they killed that too. On September 7, 2005, just 20 months after the iPod Miniʼs introduction, Apple discontinued it and launched the iPod Nano, an even smaller device that used flash memory — and had less storage (2GB and 4GB, versus 4GB and 6GB for the Mini). 36 Apple disrupted itself again using changes in the exact same sort of media (storage) that felled market leader after market leader 30 years ago.

And now, The iPod market is decreasing every quarter, largely due to “the best iPod ever” introduced in January 2007. It is more commonly known as the iPhone. Beyond creating disruption within the MP3 player market, Apple in the end disrupted the market as a whole.

How Apple Does What It Does

Christensen and Bower, in their original article, note that well-run companies have investment processes focused on customer needs:

In well-managed companies, the processes used to identify customer needs, forecast technology trends, assess profitability, allocate resources across competing proposals for investment, and take new products to market are focused — for all the right reasons — on current customers and markets. These processes are designed to week out proposed products and technologies that do not address customersʼ needs. 37

Apple follows none of these processes. Instead:

- Apple focuses on customer needs related to user experience, not specifications

- Apple does not focus directly on profit

- Apple focuses on long-run currents, not short-term trends

- Apple chooses to produce only a few products, and does not fund competing proposals or focus on diversifying

Apple Focuses on Different Needs

When Christensen and Bower talk about meeting customer needs, they are concerned with performance and specifications.

Most well-managed, established companies are consistently ahead of their industries in developing and commercializing new technologies…as long as those technologies address the next generation performance needs of their customers. 38

However, as has been consistently noted in this article, Apple is relatively unconcerned with pure performance; on the other hand, it is obsessed with the user experience. As Gene Munster said in an analyst report,

Although Apple devices don’t necessarily launch with the biggest numbers on its spec sheet, they usually combine hardware advances with improved applications that resonate with consumers and deliver usability second to none. 39

Steve Jobs, when asked why people want to work for Apple, said,

Our DNA is as a consumer company — for that individual customer who’s voting thumbs up or thumbs down. That’s who we think about. And we think that our job is to take responsibility for the complete user experience. And if it’s not up to par, it’s our fault, plain and simply. 40

This article has already laid out many of the strategic benefits of this intense focus on the user experience: it creates significant differentiation, sets customer expectations, and makes it impossible to overshoot customer needs — products are never “good enough” with regard to the user experience.

From an organizational standpoint, if products are never “good enough”, then a highly integrated company is appropriate. Chrstensen and Raynor note in the Innovatorʼs Solution that the “not-good- enough circumstance mandate[s] interdependent product or value chain architectures and vertical integration.”

Another way to look at Appleʼs decisions regarding its organizational structure is to think of transaction costs: normally, in well-functioning markets, vertical integration is suboptimal. However, if transaction costs in the vertical chain outweigh the losses due to the inefficiencies of being vertically integrated, then vertical integration could be the correct course of action. Apple thinks the exact same way, but not about monetary cost; instead, the transaction costs they consider are the tax that modularization places on the user experience, and it is a cost they are not willing to bear. A central tenet is that Apple “need[s] to own and control the primary technologies behind the products [it] make[s].” 41

Apple Does Not Focus Directly on Profit

Jonathan Ive, Appleʼs vice-president of Industrial Design, stated this very explicitly:

Apple’s goal isn’t to make money. Our goal is to design and develop and bring to market good products…We trust as a consequence of that, people will like them, and as another consequence we’ll make some money. But we’re really clear about what our goals are. 42

This gives Ive and the designers much more latitude when it comes to developing products. For example, while developing the original iMac:

Ive and others visited a candy factory to study the finer points of jelly bean making. They spent months with Asian partners, devising the sophisticated process capable of cranking out millions of iMacs a year. The team even pushed for the internal electronics to be redesigned, to make sure they looked good through the thick shell. It was a big risk for Jobs, Ive, and Apple. Says one rival: “I would have had to prove that transparency would increase our sales, and there’s no way to prove that.” He figures Apple spends as much as $65 per PC casing, vs. an industry average of maybe $20. 43

Another example is the iPhone4 and its specialized antenna:

When Apple’s iPhone4 was nearing production, Foxconn and Apple discovered that the metal frame was so specialized that it could be made only by an expensive, low- volume machine usually reserved for prototypes. Apple’s designers wouldn’t budge on their specs, so Gou [Foxconnʼs CEO] ordered more than 1,000 of the $20,000 machines from Tokyo-based Fanuc. Most companies have just one. 44

If there is ever a choice between enhancing the user experience of a product or improving its profitability, Apple, unlike nearly any other company, chooses the former, cementing the strategic advantages conferred by a focus on the user experience.

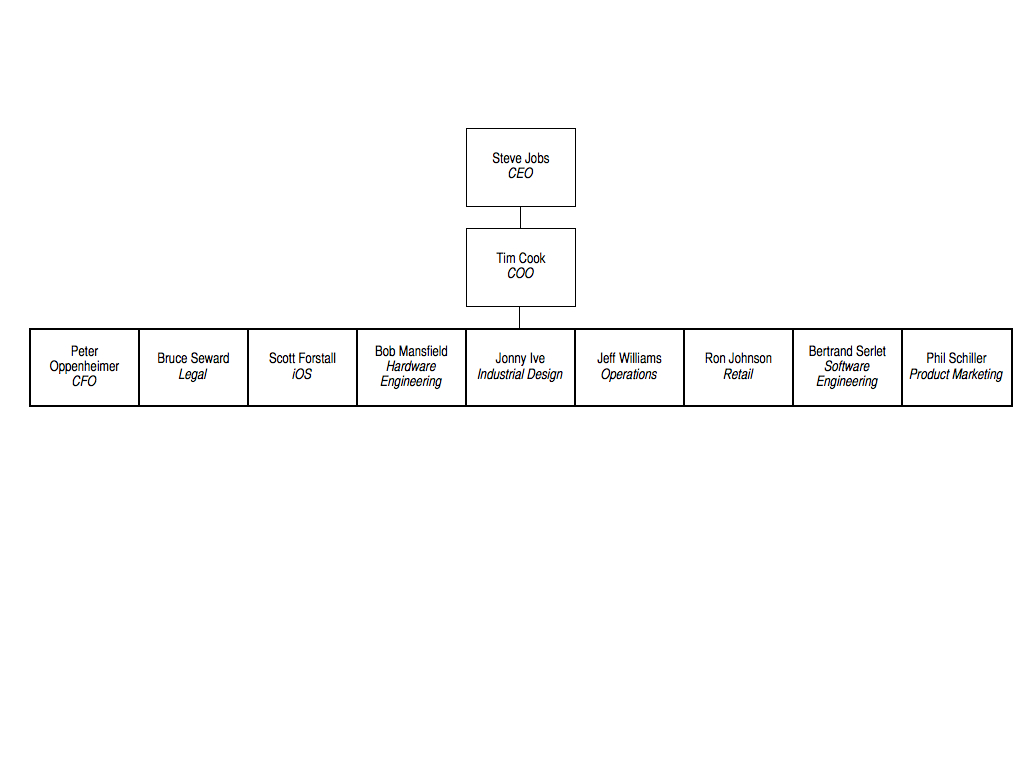

Appleʼs organizational structure is similarly focused on delivering excellent products and enabling expertise, not profit. Apple is organized functionally as seen by the structure of its executive board:

Consider the iPhone: there is no vice-president for iPhone. Rather, there is a vice-president of iOS, the software; a vice-president of hardware engineering; a vice-president of industrial design; a vice-president of operations; and a vice- president of product marketing. Each is of equal stature and expected to contribute according to their function — to deliver against a profit-and-loss number is organizationally impossible.

Apple Focuses on Long-term Currents, not Short-term Trends

Apple only enters markets that it believes will cover the entire consumer market and which are increasing in importance. According to Jobs,

Things happen fairly slowly, you know. They do. These waves of technology, you can see them way before they happen, and you just have to choose wisely which ones you’re going to surf. If you choose unwisely, then you can waste a lot of energy, but if you choose wisely it actually unfolds fairly slowly. It takes years…

[Apple] realized one day that 90% of the people who use a PDA only take information out of it on the road. They don’t put information into it. Pretty soon cellphones are going to do that, so the PDA market iss going to get reduced to a fraction of its current size, and it won’t really be sustainable. So we decided not to get into it. If we had gotten into it, we wouldn’t have had the resources to do the iPod. We probably wouldn’t have seen it coming. 45

According to Tim Cook, Apple Chief Operating Officer, in those developing areas, “We participate only in markets where we can make a significant contribution.” 46

This also fits Appleʼs structure. By focusing on delivering new-to-the-world solutions in emerging markets, Apple ensures it is competing in the “not- good-enough” segment of the market where integrated providers are at an advantage, instead of the “more-than-good-enough” follower market where modularized competitors have an advantage.

Apple Only Makes a Few Products Very Well

Given Appleʼs market cap, it is amazing to consider that it has only four main product lines and 14 main products.

The first reason for this focus is so that Apple can deliver on the user experience. Jonathan Ive said, “When you do everything to make the very best product, it also means you’re very focused on just a few products.”

This also leaves Apple free to pursue new opportunities, as in the case of the iPod. Moreover, it makes Appleʼs unique organizational structure possible. Dupont pioneered todayʼs modern organization structure with multiple profit- and-loss centers after World War I because functional organizations simply donʼt scale to multiple product lines, and they wanted to sell paint in addition to gun powder. 47 When you consider the fact that Appleʼs organizational structure is integral to its strategy of obsessively focusing on the user experience, then limiting the product line to preserve that structure is much more understandable.

The Big Question

There remains, of course, one final question: exactly how do you know what products are best, what customers need, and what constitutes a great user experience? After all, this gets back to the crux of The Innovatorʼs Dilemma — that companies fail by being too close to their customers. Apple certainly differs from other companies in itʼs approach to market research. According to Jobs,

We do no market research. We don’t hire consultants. The only consultants I’ve ever hired in my 10 years is one firm to analyze Gateway’s retail strategy so I would not make some of the same mistakes they made [when launching Apple’s retail stores]. But we never hire consultants, per se. We just want to make great products. 48

Instead, Apple relies on self-reflection and discipline:

It’s not about pop culture, and it’s not about fooling people, and it’s not about convincing people that they want something they don’t. We figure out what we want. And I think we’re pretty good at having the right discipline to think through whether a lot of other people are going to want it, too. That’s what we get paid to do.

So you can’t go out and ask people, you know, what the next big [thing.] There’s a great quote by Henry Ford, right? He said, “If I’d have asked my customers what they wanted, they would have told me ʻA faster horse.ʼ “ 49

Many will read this quote and despair at ever having a Steve Jobs run their company. But I believe that for all of Jobs brilliance, the secret of Appleʼs success is about design and a different way of thinking. Design at its essence, is not just about form, and not just about function. Instead, itʼs both, and more. It is ultimately about the user and delivering exactly what they need, not just what they say they want. Apple takes it as their responsibility — what customers pay them for — to both know technology and customers better than customers know themselves and deliver products that truly surprise and delight. And it is suprise and delight that builds a powerful and long-lasting brand that goes from success to success without any dilemma at all.

Moreover, it is a way of thinking that Apple does not have a monopoly over. It requires acknowledging that there are product attributes that cannot be measured, and that value means much more than money. It also requires thoughtfulness and patience, and a broad appreciation of people and culture. Escaping the Innovatorʼs Dilemma is about escaping the operational mindset that is the current ideal in much of business. In short, there are few other companies like Apple because no one dares or is allowed to think different, not because it is impossible.

Of course, itʼs worth remembering that Henry Ford was disrupted, and rather abruptly at that. Appleʼs course, like all high reward ones, is also high risk. Stringently focusing on just a few products and saying no to a hundred more requires extreme discipline on the part of the CEO, as well as significant respect within the ranks for the CEOʼs decisions. Jobs has both, but whether or not his successor will is another question. A second risk raised by Appleʼs extreme focus is the possibility of getting it wrong with one of their core products. Without a diversified portfolio, a significant misstep could be extremely costly. Another challenge is maintaining the intrinsic motivation that compels employees to create amazing products despite no direct compensation for doing that (outside of stock options). However, the biggest risk in my mind is forgetting the lessons of the 90s when Apple was disrupted. In many respects it seems that nearly going bankrupt drove many of the strategic decisions recounted here, and other companies ought to better understand and emulate Apple now before Apple itself forgets how it got here.

- CapitalIQ.com [ ↩ ]

- Bower, Joseph and Christensen, Clayton. “Disruptive Technologies: Catching the Wave” Harvard Business Review, January-February 1995, page 4-5 [ ↩ ]

- Bower, Christensen, p. 5-6 [ ↩ ]

- Bower, Christensen, p.3 [ ↩ ]

- Bower, Christensen, p.3 [ ↩ ]

- Christensen, Raynor, The Innovatorʼs Solution (Kindle Edition), Harvard Business School Press, 2003, Retrieved from Amazon.com, Location 1603-1615 [ ↩ ]

- Christensen, Raynor, l.1629-1636 [ ↩ ]

- Figure 1, which is the basis for all the figures that follow, is adapted from Figure 5-1 in the Innovatorʼs Solution, Christensen, Raynor, l. 1590 [ ↩ ]

- Apple, Inc. Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apple_Inc. [ ↩ ]

- CapitalIQ.com [ ↩ ]

- Christensen, Raynor, l. 1653 [ ↩ ]

- CapitalIQ.com [ ↩ ]

- Hesseldahl, Arik, The iPod in Perspective, Forbes, October 15, 2004 http://www.forbes.com/2004/10/15/cx_ah_1015tentech.html [ ↩ ]

- Burrows, Peter, Can the iPod Keep Leading the Band?, BusinessWeek, November 8, 2004 http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/04_45/b3907064_mz011.htm [ ↩ ]

- Salkever, Alex, A Bitter Apple Replay?, Bloomberg, October 14, 2004, http://www.businessweek.com/technology/content/oct2004/tc20041014_9962_tc056.htm] [16. This entire article is worth reading in its entirety as it is a nearly perfect encapsulation of the industry conventional wisdom [ ↩ ]

- Graph compiled from http://www.theregister.co.uk/2004/10/12/ipod_us_share/, http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/2005/10/31/8359167/index.htm, http://www.ibtimes.com/articles/20061004/apple-ipod-market-share.htm, http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&refer=us&sid=aSevgh8PDACE, http://apcmag.com/apples_announces_new_ipods_itunes_8_and_an _upgrade_for_iphone_users.htm, http://www.afterdawn.com/news/article.cfm/2009/09/09/ipod_market_share_at_73_8_percent_225_million_ipods_sold_more_games_for_touch_than_psp_nds_apple, http://www.businessinsider.com/through-may-apples-ipod-had-76-of-the-us-mp3-player- [ ↩ ]

- Pogue, David, iPodʼs Law: The Impossible is Possible, New York Times, September 15, 2005, http://www.nytimes.com/2005/09/15/technology/circuits/15pogue.html [ ↩ ]

- Menta, Richard, We Test Drive the Creative Nomad Jukebox, MP3newswire.net, November 21, 2000, http://www.mp3newswire.net/stories/2000/nomadreview.html [ ↩ ]

- iTunes Store, Wikipedia.com, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Itunes_store [ ↩ ]

- Notes: Apple renames iTunes Store, acquires Cover Flow, AppleInsider.com, http://www.appleinsider.com/articles/06/09/13/notes_apple_renames_itunes_store_acquires_co ver_flow.html [ ↩ ]

- McGuire, Mike; Baker, Vin, Apple’s iPod and iTunes Updates Keep Pressure on Competitors; Apple TV Revamp Takes It Beyond a ‘Hobby’, Gartner, September 24, 2010 [ ↩ ]

- Gamet, Jeff, Analyst: Facetime Driving Many iPhone 4 Sales, The Mac Observer, June 24, 2010, http://www.macobserver.com/tmo/article/analyst_facetime_driving_many_iphone_4_sales/ [ ↩ ]

- King, Brad, Appleʼs ʻBreakthroughʼ iPod, Wired, October 23, 2001, http://www.wired.com/gadgets/miscellaneous/news/2001/10/47805 [ ↩ ]

- Lloyd, Dennis, A Brief History of iPod, iLounge, http://www.ilounge.com/index.php/articles/comments/instant-expert-a-brief-history-of-ipod/ [ ↩ ]

- Menta, Richard, iPod Killers for Christmas, MP3newswire.net, October 14, 2004, http://www.mp3newswire.net/stories/2004/XmasPlayers.html [ ↩ ]

- Horwitz, Jeremy, When Apple Waits, Competitors Strike, iLounge, July 2, 2004, http://www.ilounge.com/index.php/articles/comments/analysis-when-apple-waits-competitors-strike/ [ ↩ ]

- Block, Ryan, Steve Jobs Live – Appleʼs “The Best Goes On” Special Event, Engadget, September 5, 2007, http://www.engadget.com/2007/09/05/steve-jobs-live-apples-the-beat-goes-on-special-event/ [ ↩ ]

- Menta, Richard, iPod Killers: 30 New Players for the Holidays, MP3newswire.net, October 13, 2007, http://www.mp3newswire.net/stories/7002/iPod-Killer-Holiday2007.html The introduction to this article is quite instructive:

文章版权归原作者所有。