How Apple Creates Leverage, and the Future of Apple Pay

How Apple Creates Leverage, and the Future of Apple Pay

Tim Cook said something very revealing on last quarter’s earnings call :

Last month we introduced two new categories; the first is Apple Pay, an entirely new way to pay for things in stores and in apps…The second new category is Apple Watch, our most personal device ever and one that has already captured the world’s imagination.

Did you catch that? Cook put Apple Pay on the same level as Apple Watch. It is no hobby.

Something that has characterized most of Apple’s recent successes is the degree to which they have depended on partnerships with normally intractable industries. 1 The two most obvious examples are iPod/iTunes and the music industry, and most obviously, the iPhone and the phone carriers. This perhaps seems counterintuitive: Apple is famous for being difficult to deal with, working diligently to ensure it always has the upper hand, even as it holds its partners to impossible standards.

This reading of Apple’s partnership abilities, though, mistakenly rests on the assumption that business deals grow out of personal affinity. The truth is that while personal likability may help on the margins, the controlling force in Apple’s negotiations is cold hard business logic. Thus, in order to understand why Apple has been so successful in previous partnerships – and, looking forward, to better estimate the chances of Apple Pay becoming widespread – it is essential to understand how the company acquires and uses leverage.

The most important term in the study of negotiation is BATNA: Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement. Your BATNA defines the point at which you are willing to walk away from a deal. In order to “win” a negotiation, you want to make your BATNA as high as possible, so it’s easy for you to walk away, even as you work to make your counterparty’s BATNA as low as possible, so that they will concede more than they would like. Leverage is the means by which you change your counterparty’s BATNA.

When the iTunes Store née iTunes Music Store launched in early 2003, 2 Apple was a very different company than they are today. The iPod had been on the market for a year-and-a-half, but it only worked with a Mac, which was still stuck at well under 5% of the market. This, though, worked to Apple’s advantage in their negotiations with the music labels: not only did Apple not have much to lose, but the labels didn’t really see Apple as being a major player. The labels were far more concerned about the widespread sharing of music online; suing Napster to oblivion simply made music sharing more distributed and harder to control, which, of course, benefited Apple: their customers had alternate means with which to fill their iPods. So when Apple showed up with an offering to build a music store for their small audience, well, why not?

Just a few months later, Apple expanded iTunes to Windows, and what could the labels say? Despite the fact it only existed on the Mac, the iTunes Music Store was already the number one music download service in the world. It turned out Apple had another ace in the hole: a customer base that, while small, had an outsized willingness and ability to spend. After all, they had already dropped at least $1,500 on a Mac and iPod (and likely a lot more), what was an extra $0.99? At a more basic level, said customers were loyal to Apple not because it made sense from a feature or price perspective, but simply because they loved and valued the experience of using Apple products. That, ultimately, was the key to Apple’s favorable position: they had the best customers because they had the best user experience; if the labels wanted access to them, they had to agree to Apple’s terms.

Over time the labels’ addiction to iTunes revenues only deepened, and by 2008 iTunes was their biggest source of revenue. Music executives would rant and rave about Apple’s power, and try to increase their own leverage by, for example, allowing DRM-free songs on Amazon but not Apple, but it didn’t matter because Apple had the best experience, and thus the best customers.

Apple’s negotiations with the music labels was just a warmup for the phone carriers. While Apple in 2006 (in the runup to the iPhone) was in a much stronger position than 2003, they were still much smaller ($60.6 billion market cap) than AT&T ($102.3 billion) or Verizon ($93.8 billion) on an individual basis, much less the carrier industry as a whole. More importantly, carriers weren’t facing a collective existential threat like piracy, which significantly increased their BATNA relative to the music labels.

The music labels, though, benefitted from a relatively low elasticity of substitution: if I wanted one particular band that wasn’t on the iTunes Music Store, I wouldn’t be easily satisfied by the fact another band happened to be available. The carriers, on the other hand, largely offered the same service: voice, SMS, and data, all of which was interoperable. This increased elasticity of substitution gave Apple an opportunity to pursue a divide-and-conquer strategy: they just needed one carrier.

Apple reportedly started iPhone negotiations with Verizon, but it turned out that Verizon was already kicking AT&T’s (then Cingular’s) butt through aggressive investment and technology choices, resulting in increasing subscriber numbers largely at AT&T’s expense. Verizon saw no need to change their strategy, which included strong branding and total control over the experience on phones on their network. AT&T, meanwhile, was on the opposite side of the coin: they were losing, and that in turn had a significant effect on their BATNA – they were a lot more willing to compromise when it came to branding and the user experience, and so the iPhone launched on AT&T to Apple’s specifications.

That is when Apple’s user experience advantage and corresponding customer loyalty took over: for the first time ever customers were willing to endure the hassle and expense of changing phone carriers just so they could have access to a specific device. Over the next several years Verizon began to bleed customers to AT&T even though their service levels were not only better, but actually widening the gap thanks to the iPhone’s impact on AT&T. Four years after launch the iPhone did finally arrive on Verizon with the same lack of carrier branding and control over the user experience; in other words, Verizon eventually accepted the exact same deal they rejected in 2006 because the loyalty of Apple customers gave them no choice. 3

Apple followed the same playbook in country after country: insistence on total control (and over time, significant marketing investments and a guaranteed number of units sold) with a willingness to launch on second or third-place carriers if necessary. Probably the starkest example of the success of this strategy was in Japan. Softbank was in a distant third place in the Japanese market when they began selling the iPhone in 2008; finally after four years second-place KDDI added the iPhone, but only after Softbank had increased its subscriber base from 19 million to 30 million. NTT DoCoMo, long the dominant carrier and a pioneer in carrier-branded services finally caved last year after seeing its share of the market slide from 52% in 2008 to 46%. Apple had all the leverage, because they had customers who cared more about the iPhone than they did their carrier.

Apple is certainly not shy about proclaiming their fealty towards building great products. And I believe Tim Cook, Jony Ive, and the rest of Apple’s leadership when they say their focus on the experience of using an Apple device comes from their desire to build something they themselves would want to use. But I also believe the strategic implications of this focus are serially undervalued.

Last year I wrote a piece called What Clayton Christensen Got Wrong that explored the idea that the user experience was the sort of attribute that could never be overshot; as long as Apple provided a superior experience, they would always win the high-end subset of the consumer market that is willing to pay for nice things.

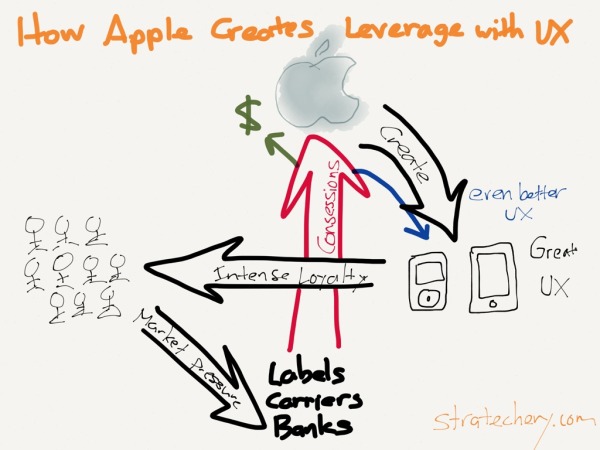

However, this telling of the story of iTunes and the iPhone suggests that this focus on the user experience not only defends against disruption, but it also provides an offensive advantage as well: namely, Apple increases its user experience advantage through the leverage it gains from consumers loyal to the company. In the case of iTunes, Apple was able to create the most seamless music acquisition process possible: the labels had no choice but to go along. Similarly, when it comes to smartphones, Apple devices from day one have not been cluttered with carrier branding or apps or control over updates. If carriers didn’t like Apple’s insistence on creating the best possible user experience, well, consumers who valued said experience were more than happy to take their business elsewhere. In effect, Apple builds incredible user experiences, which gains them loyal customers who collectively have massive market power, which Apple can then effectively wield to get its way – a way that involves maximizing the user experience. It’s a virtuous circle:

Understanding this circle and how it interacts with the relevant actors is the key to evaluating the prospects of Apple Pay.

When it comes to Apple Pay adoption, there are five collective players that matter: Apple, Apple customers, credit card networks (Visa, Mastercard and American Express 4 ), banks, and merchants.

- Apple has, as is their wont, spent a significant amount of time on the Apple Pay experience. Over the last several years they have built the various pieces of Apple Pay, including Touch ID, their own chips (which include the secure enclave), an experimental NFC antenna design, as well as the software to make it work, with the bonus of 800 million credit cards stored in iTunes ready to be potentially added

文章版权归原作者所有。