Tidal and the Future of Music

Tidal and the Future of Music

I’m a couple of days late in writing about Tidal, Jay Z and friends’ new streaming service , so I’ve been saved the trouble of predicting it will fail. The most scathing and, unsurprisingly, best critique was levied by Bob Lefsetz . This is the key paragraph:

Suddenly, just because Jay Z is a famous musician he expects all of his fans to pony up ten bucks a month? Raw insanity. As is the position of the artists on the stage. I’d be much more impressed if they all ankled their deals, got rid of the major labels and went it alone. That’s why they’re not making much money on Spotify, not because of the free tier, but because their deals suck. But these same deals apply on Tidal! They’ve got to license the music from their bosses! It’s utterly laughable, like nursery school kids plotting against the teacher, or a kindergartner running away from home. Grow up!

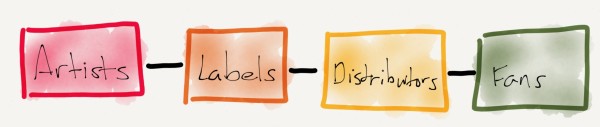

Lefsetz’s criticism is based on the basic structure of the music industry:

The role of three of the four is obvious:

- Artists make the music

- Distributors (Apple, Spotify, YouTube, Pirate Bay, etc.) get the music to fans

- Fans listen to the music

The more interesting question is about labels: why do they still exist, and why do every single one of the artists behind Tidal remain attached to them?

The Role of Record Labels

In the pre-Internet era (or, to be more precise, the pre-Napster era) one of the roles of labels was obvious: they handled distribution. Actually making and distributing a bunch of records (or 8-tracks or cassettes or CDs) was a capital-intensive task that required significant investment in production lines, channel development, and logistics. As with many such businesses, it was the cost structure of these activities – significant fixed costs, but relatively small marginal costs (a CD costs pennies to make) – that determined the business model: an outsized focus on big hits. The New York Times broke this down back in 1995:

Setting prices “is very arbitrary,” said a top executive at a major label, who described his company’s pricing policies only on condition of anonymity. “We’re trying to raise CD prices,” he said. “The reason for this is that our costs are escalating in such a marginal way, everything from marketing to promoting to signing bands. It costs $400,000 to $600,000 to sign a band. The first video costs a minimum of $50,000. Touring is more expensive, and people’s salaries are a lot higher. Our profit margins are being squeezed.

“It’s a very speculative business that we’re in. If a label can break one new band a year, they’re having a good year. The first 300,000 to 500,000 copies a record label sells of most CD’s don’t make money. That’s 80 percent of all records that don’t make money; the other 20 percent have to pay for the 80 percent.”

There’s a bit of circular logic here – many artists are unprofitable because of marketing and promotional (fixed) costs, but the ever-higher marketing and promotional costs existed because of the pursuit of breakout winners, which are necessary to cover the ever increasing fixed costs. 1 Still, the logic makes sense. The reality is that a Jay Z or Coldplay will more than pay for a whole roster of unprofitable artists, and this has always been the case.

This is why, by the way, I’m generally quite unsympathetic to artists belly-aching about how unfair their labels are. Is it unfair that all of the artists who don’t break through are not compelled to repay the labels the money that was invested in them? No one begrudges venture capitalists for profiting when a startup IPOs, because that return pays for all the other startups in the portfolio that failed.

In fact, this gets to the first reason why labels are still relevant: although the distribution function has gradually gone away (although, CDs still made up over 50% of all album sales in 2014), the venture capital function of record labels remains. Apple, Spotify, et al are not interested in discovering and speculatively funding new artists; it’s a difficult and specialized job and the labels are quite good at it. And, like the best sort of VCs, record labels don’t just provide money but also guidance in both an artist’s sound and their business dealings.

Of course labels don’t just find artists who magically become popular: the record labels also help make them so with the aforementioned marketing and promotion costs. This can be everything from getting artists booked on TV, featured in iTunes, or promoted on blogs, but the biggie, even in 2015, is getting artists on the radio. According to the Nielsen 2014 Year End Music Report radio remains the number one source of music discovery: an amazing 91.3% of the U.S. population listens to the radio at least once-a-week, and 51% of those surveyed based their buying decisions off of what they heard on the radio. Record labels have entire divisions devoted to getting their artists on the radio, and while the old under-the-table payments have been outlawed, there still is no expense spared when it comes to getting in front of listeners. Marketing is expensive, and the competition is steep.

The Motivation of Artists

This is why Jay Z and his chart-topping partners are taking on Spotify, not their labels. Jay Z is the extreme example here: he has his own label that deals with artists directly, but Roc Nation is a part of Universal Music Group , which handles distribution, and is financed by Live Nation (making a move into the record labels business) to the tune of $150 million over 10 years. Jay Z isn’t giving that money back so that he can make his music exclusive to Tidal, nor are any of the other artists.

Moreover, even if Jay Z and company were truly independent, they would be heavily incentivized to avoid exclusivity as well: remember that music has high fixed costs but (especially on the Internet) zero marginal costs. That means the best way to make money is to sell as many units as possible in order to spread out those fixed costs. That, by extension, means the optimal strategy for whoever owns the music is making it available in as many places as possible – the exact opposite of an exclusive. 2

This ultimately is why Tidal will fail: it’s nice that Jay Z and company would prefer to garner Spotify’s (minuscule) share of streaming revenue, but there is zero reason to expect Tidal to win in the market. Not enough people care – or are even capable of appreciating – the hi-fi option, 3 and unlike Beats headphones (but like Beats the music service) software isn’t a status symbol. Moreover, Tidal doesn’t have Spotify’s head-start or free tier, it doesn’t have Apple’s distribution might and bank account, and it doesn’t have any meaningful exclusives 4 — and to be successful, you need a lot of exclusives; it’s too easy and guilt-free to pirate (or simply skip) one or two songs.

Looking Forward

The key to the record label’s resilience is that their role has always been about more than distribution; it has also been about discovery, funding, and promotion. Each of these is under threat in different ways:

- Discovery: A combination of social media and YouTube has made it massively easier for a musician to spread via word-of-mouth. On the back-end, tools like Shazam are providing real data about what artists are blowing up long before a traditional record label would ever notice. Both of these channels are much more actionable for one of the distribution companies (Apple, 5 Google/YouTube, and Spotify) than a traditional talent discovery process

- Funding: The cost of producing a basic record has come down dramatically over the years. Sure, things like samples and extensive production raise those costs, but those are also often the luxuries of the already-established. Thanks to computers an artist can put together something good enough to get noticed for remarkably little money 6

- Promotion: The more that distribution moves away from CDs and to online channels, the more valuable those channels become in terms of promotion. iTunes already has significant expertise in this regard, and I wouldn’t be surprised if Apple in particular is considering an acquisition of Pandora to give Beats an even stronger promotional channel

Still, it’s often far easier to theorize an industry’s downfall than it is to actually effect it. The fact remains that the labels can – and do – take just as much advantage of social and Shazam data as anyone else, and they retain a core competency in developing and nurturing raw material into something popular. Moreover, sometimes better music costs money, and the record labels remain the only source. Finally, promotion generally and radio generally remain a big deal: the more noise there is, the more valuable is the ability to break through the noise.

I would again draw an analogy to venture capital: startups can spread via Twitter or new discovery services like Product Hunt; minimum viable products are cheaper to build than ever thanks to Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, etc.; and distribution channels like App Stores have natural promotional channels. And yet the importance – and amount – of venture capital has never been greater. The truth is that because so many folks can now get started it is that much harder – and more expensive – to cut through the noise. Consumer companies need massive growth for many years, and enterprise companies need expensive salesforces, and the only folks enabling both are venture capitalists.

The Exceptions

There is one big problem with this story of continued label importance: Macklemore. The Seattle rap artist made it to the top of the charts – multiple times – and won multiple Grammys 7 without the help of a label. Techdirt transcribed a podcast where Macklemore explained his path:

With the power of the internet and with the real personal relationship that you can have via social media with your fans…I mean everyone talks about MTV and the music industry, and how MTV doesn’t play videos any more — YouTube has obviously completely replaced that. It doesn’t matter that MTV doesn’t play videos. It matters that we have YouTube and that has been our greatest resource in terms of connecting, having our identity, creating a brand, showing the world who we are via YouTube. That has been our label. Labels will go in and spend a million dollar or hundreds of thousands of dollars and try to “brand” these artists and they have no idea how to do it. There’s no authenticity. They’re trying to follow a formula that’s dead. And Ryan and I, out of anything, that we’re good at making music, but we’re great at branding. We’re great at figuring out what our target audience is. How we’re going to reach them and how we’re going to do that in a way that’s real and true to who we are as people. Because that’s where the substance is. That’s where the people actually feel the real connection.

Macklemore now works with labels on distribution – CDs still sell! – but he hires them, he doesn’t give away everything before he’s even started. Is he an exception that proves the rule, or the start of a wave?

In the short term I think the former, but the long term is very much an open question: there’s no question the world is changing. Returning to Lefsetz, he made a similar observation in an article about BuzzFeed Motion Pictures :

Are you watching this? It’s kind of like digital photography. We heard about it for a decade and then it happened overnight. We heard about internet delivery of television programs and in the last two weeks, it’s arrived.

And what do people want to see? That’s BuzzFeed’s mission. To capture eyeballs. And to replace the cable TV producers. [Head of BuzzFeed Motion Pictures] Ze [Frank] thinks their model stinks. Thinks the music labels’ model stinks. Wherein you throw a ton of money at the wall and hope something sticks to pay for it all. Ze believes you’ve got to pay as you go. Everything’s got to win…

The key is to create content people can identify with, see themselves in, that they can access at any time. Length, story? Irrelevant…Which is why you’d rather work at BuzzFeed Motion Pictures. Where you get to put your hands on the wheel. Where you’re the master of your own domain. Where you can become a star.

“Become”, not “are.” This is the biggest problem with Tidal. The stars of today would like a few more pennies-per-stream. It’s the stars of tomorrow, though, that will decide the music industry’s fate, and while I might think Jay Z the better rapper, it’s very much possible that Macklemore is the greater inspiration. 8

- When the unnamed executive refers to costs “escalating in such a marginal way” he is referring to the way marketing spend increases with each artist; marketing, though, is a fixed cost for any one album. The more albums you buy, the less the marketing costs on a per-album sold basis [ ↩ ]

- Longtime readers will make the connection to my arguments as to why Google’s services will always work on the iPhone, and why I was so aghast at Microsoft strategy of using their services to differentiate Windows Phone (since abandoned, thankfully): both companies have horizontal business models that dictate a strategy of reaching as many consumers as possible. This is the case for most services, and Apple’s are the exception that proves the rule: their services serve to differentiate their hardware, which is where they make money, thus the exclusivity [ ↩ ]

- If anything the hi-fi offering has hurt Tidal by anchoring the price at $20/month in too many people’s minds [ ↩ ]

- Some outlets are reporting that Tidal has exclusive rights to Taylor Swift’s back catalog, but that’s incorrect; Swift’s catalog is available on any streaming service that doesn’t have a free tier [ ↩ ]

- This is another potential angle to Apple’s Topsy acquisition [ ↩ ]

- This is the biggest different from video, in my opinion. Quality television is still significantly more expensive than self-produced content; the delta in music is less (and dramatically less when it comes to text) [ ↩ ]

- Which should have gone to Kendrick Lamar, but that’s neither here nor there [ ↩ ]

- Speaking of business models only, mind you! I bet Jay Z, who himself couldn’t get a label at the beginning and who has proven to be a brilliant businessman, would follow the same path were he starting today [ ↩ ]

文章版权归原作者所有。