Unicorns

Unicorns

The entire point of the name “Unicorn”, first coined by Aileen Lee in November 2013 , is to describe something very rare: “U.S.-based software companies started since 2003 and valued at over $1 billion by public or private market investors” was Lee’s definition.

Over the last year-and-a-half the definition has changed a bit — most include international startups, and limit the list to private companies — but the biggest difference is the number of companies that qualify: Fortune’s Unicorn List has 100 companies on it, a big jump over the 39 counted by Lee. 1 Many, including Andreessen Horowitz in a presentation entitled U.S. Tech Funding — What’s Going On? , have argued the reduction of a unicorn to something more akin to a zebra — exotic, but not exactly rare — is due to a shift in money from tech IPOs to late stage growth rounds. In the presentation these growth rounds are defined as rounds of >$40 million and given the label “quasi-IPOs”:

Bill Gurley, for one, made clear he’s not buying this blurring of the lines in a March post aptly titled Investor’s Beware: Today’s 100M+ Late-stage Private Rounds Are Very Different from an IPO :

Some have argued that each of these companies would already be public in a prior era. Buying into such a notion is dangerous – dangerous for the entrepreneur and dangerous for the investor. Actually, very few of these companies are at a point where they could or should consider being public. Lost in this conversation are the dramatic differences between a high priced private round and an IPO. Understanding these differences is crucial to understanding the true risks in this large private-round phenomenon.

Gurley is particularly concerned with the lack of scrutiny for non-public companies, along with the ease with which unicorns can “mischaracterize their financial positioning relative to industry standard or norm.” The Wall Street Journal highlighted the latter concern last week:

As young technology companies jostle for investors who will pour money into the firms as they try to make it big and strike it rich, some companies are using unconventional financial terms. Instead of revenue, these privately held firms tout “bookings,” “annual recurring revenue” or other numbers that often far exceed actual revenue.

The practice is perfectly legal and doesn’t violate securities rules because the companies haven’t sold shares in an initial public offering. Public companies can use “non-GAAP” financial terms but must explain them and disclose how they differ from measurements that follow strict accounting rules…

Skeptics claim that the practice is yet another sign that the tech sector is plagued with overconfidence and setting itself up for a fall. They say investors who go along with vague, unconventional financial terms are inflating valuations and leaving almost no room for error at fledgling technology companies.

For his part Gurley has said on several occasions that there will “be some dead unicorns this year”; for the sake of argument, let’s say that he’s right. 2 The question, then, is whether or not a dead unicorn (or ten) means the bubble has popped — or perhaps more accurately, whether or not there were a bubble at all.

Last week Chris Dixon described The Babe Ruth Effect in Venture Capital : the idea that swinging for the fences (10x returns) necessarily means more strikeouts (failed investments).

The Babe Ruth effect occurs in many categories of investing, but is especially pronounced in VC. As Peter Thiel observes :

Actual [venture capital] returns are incredibly skewed. The more a VC understands this skew pattern, the better the VC. Bad VCs tend to think the dashed line is flat, i.e. that all companies are created equal, and some just fail, spin wheels, or grow. In reality you get a power law distribution…

What is interesting and perhaps surprising is that the great funds lose money more often than good funds do. The best VCs funds truly do exemplify the Babe Ruth effect: they swing hard, and either hit big or miss big. You can’t have grand slams without a lot of strikeouts.

Dixon’s post is about the performance of individual venture capital firms, but I think the Babe Ruth framework is a useful way to think about the current crop of unicorns. Indeed, a close look at the valuations of the actual companies involved shows the exact sort of skew Thiel was talking about: 3

The line is a power curve — even unicorns fit the expected venture capital return. This has one really important implication that should shape the way we talk about unicorns and whether or not there is a bubble. Namely, for tech broadly nothing matters outside of ~10 or so companies :

- Xiaomi and Uber alone account for 22% of Unicorn valuation

- The top 10 most valuable companies ( Xiaomi, Uber, Airbnb, Palantir, Snapchat, SpaceX, Flipkart, Pinterest, Dropbox, Theranos ) account for 49% of Unicorn valuations

- The top 20 account for 65% of Unicorn valuations

Anything that happens to any of these companies is a big deal when it comes to the overall health of the startup ecosystem; anything that happens outside isn’t. To put it in concrete terms, if Dropbox, probably the most fragile of the top 10 ( members-only ), were to have a down round or sell itself for less than its valuation, that would be a very big story. If Evernote, which is suddenly changing its CEO , were to do the same, it wouldn’t be nearly as big a deal. Keep this in mind when and if Gurley’s predicted unicorn deaths occur.

On the flip side, should a few of these top unicorns finally go public and validate their valuations, nearly the entire unicorn cohort would come out ahead. The entire list of 100 has raised around $55 billion collectively, which is about the same as the combined valuation of any three of the top 10 (or any two if one of the set is Uber or Xiaomi). 4

There’s another insight to be drawn from that $55 billion collective investment: it turns out its distribution fits a linear curve much more closely than a power curve (at least once you remove Uber from the calculation):

This too echoes what you might expect at an individual VC firm — you invest equally, but profit unequally — but given that no VC firm is invested in every unicorn, there will clearly be winners and losers when it comes to individual firm performance. It’s possible (and probably likely) that the industry comes out ahead in the aggregate even as a significant majority of individual venture capital firms lose money.

I’ve previously laid out why It’s Not 1999 : these unicorns are real companies with real business models and real revenues. Profitability is lagging, but given said business models — SaaS in the enterprise, and mostly ads in consumers — that’s to be expected. Most importantly, there simply isn’t the sort of public market froth that made the last bubble so contagious.

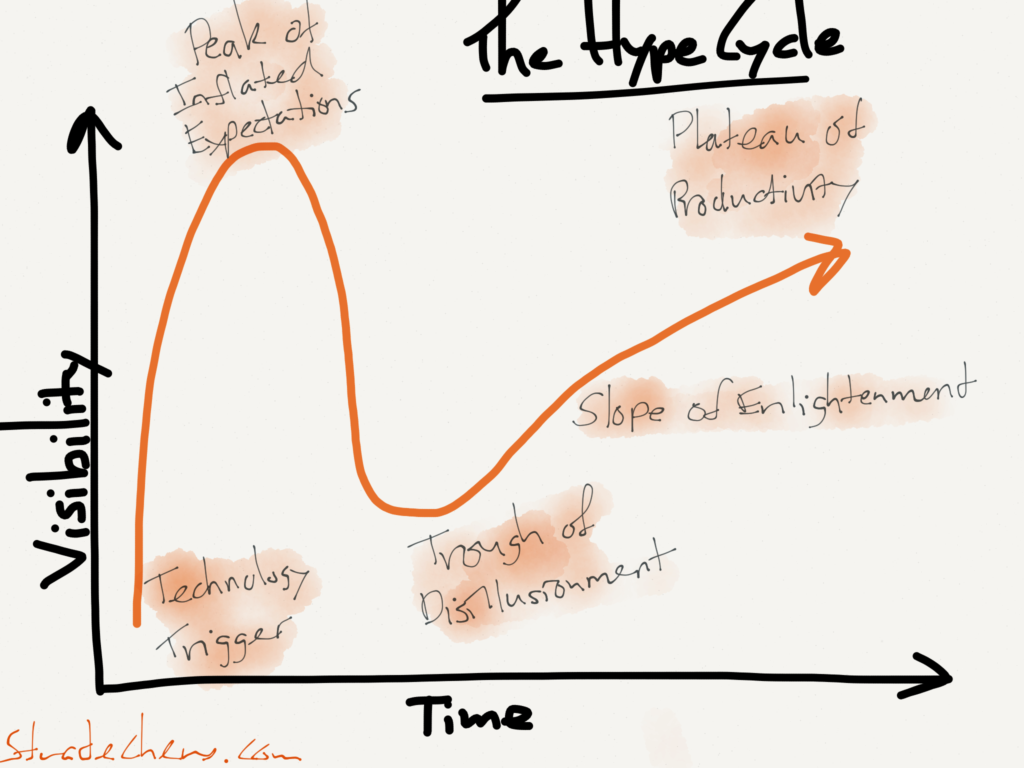

Indeed, I suspect that 1999 was less a cyclical peak than it was the top of the hype cycle:

- The Internet was the technology trigger

- The Dot Com era was the peak of Inflated Expectations

- The bursting of the bubble and much of the 2000s was the trough of disillusionment

- The last five years have been the slope of enlightenment

In this reading the technology industry is on the verge of the plateau of productivity, a steady march to remake industry after industry. That’s an exceptionally valuable prospect, and more than anything explains these unicorn valuations, particularly transformative market-makers like Uber or Airbnb.

To be clear, this isn’t exactly a controversial view; indeed, while macroeconomic factors like low interest rates play a role, I think a big reason for the quantity of unicorns is the fear of missing out on one of the greatest periods of value creation we have ever seen. However, some of the most valuable opportunities — particularly the aforementioned market-makers — have strong winner-take-all characteristics: this potentially limits the number of quality unicorns.

I think it’s this dichotomy that makes the current bubble discussion so difficult: most unicorns may be overvalued, but in aggregate they are probably undervalued. It turns out winner-take-all doesn’t apply just to the markets these startups are targeting, it applies to the startups themselves.

Discuss this Article in the Stratechery Forum ( members-only )

- Fortune’s and Lee’s definitions are different: Fortune includes 15 companies that were started before 2003, plus 26 international companies; on the other hand, Fortune does not include any public companies [ ↩ ]

- I suspect he is [ ↩ ]

- Valuations are drawn from the aforementioned Fortune Unicorn List ; I updated a few of them to reflect recent fundraising [ ↩ ]

- The $55 billion was drawn from Crunchbase ; it’s an estimate, as not all companies had information, some included secondary offerings, and there was a much greater chance of human error on my part [ ↩ ]

文章版权归原作者所有。