Popping the Publishing Bubble

Popping the Publishing Bubble

Over the last few weeks and months there has been increasing alarm that today, September 16, is a critical one for publishers — and by critical, I mean the diagnosis that most publishers will soon be in critical condition. After all, today Apple releases iOS 9 with support for “content blocking extensions” which will effectively enable ad blockers for Safari, iOS’s default web browser.

That it’s Safari is important; the concern about ad blockers is, for now, a bit overwrought given that a much larger proportion of page views for most publishers comes from Facebook, which, along with Twitter and most other social networks, uses a classic web view controller that isn’t affected by the new content blockers. 1 However, while the concern over ad-blockers may be too early, publisher angst is arguably too late: if iOS 9 ad blockers do end up causing serious harm it is only because the publishers have been living in an unsustainable bubble that is going to pop sooner rather than later.

The Good Old Days

In the pre-Internet era publishers had it easy: on one hand, they employed journalists whose goal it was to reach as many readers as possible. On the other, they were largely paid by advertisers, whose goal was to reach as many potential customers as possible. The alignment — reach as many X as possible — was obvious, and profitable for the publishers in particular.

It was also a great gig for the journalists. Sure, most didn’t get rich, but they received a different sort of compensation: the dispensation from needing to worry about making money. As for the advertisers, where else were they going to go? Radio and TV took their share of advertising dollars from newspapers, but both formats had only limited inventory given the fact there were a finite number of channels (or stations) and only 24 hours in a day.

The Internet Impact

The shift from paper to digital meant publications could now reach every person on earth (not just their geographic area), and starting a new publication was vastly easier and cheaper than before. This had two critical implications:

- There was now an effectively unlimited amount of ad inventory, which meant the price of an undifferentiated ad has drifted inexorably towards zero

- “Readers” and “potential customers” became two distinct entities, which meant that publishers and advertisers were no longer in alignment

This first point is obvious and well-known, but the importance of the second can not be overstated: publishers had long taken advertising for granted (or, as the journalists put it, had erected a “separation of church and state”) under the assumption they had a monopoly on reader attention. The increase in competition destroyed the monopoly, but it was the divorce of “readers” from “potential customers” that prevented even the largest publishers from profiting much from the massive amounts of new traffic they were receiving. After all, advertisers don’t really care about readers; they care about identifying, reaching, and converting potential customers. And, by extension, this meant that differentiating ad inventory depended less on volume and much more on the degree to which a particular ad offered superior targeting, a superior format, or superior tracking.

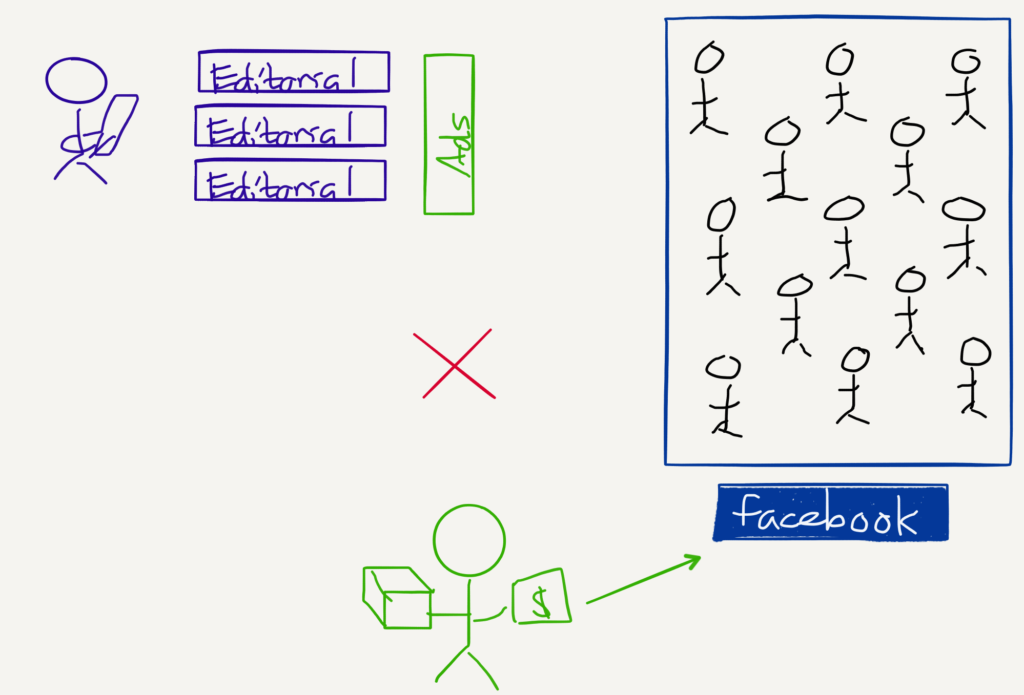

This bifurcation in incentives has resulted in a plethora of ad networks: publishers collectively provide real estate in front of collated readers, while it is the responsibility of the ad networks to identify and track prospective customers on behalf of advertisers. Note, though, the orthogonality of this relationship: publishers and ad networks are working at cross-purposes.

The result is that ad networks don’t really care about the readers — which is a big reason Why Web Pages Suck — and on the flip-side publishers don’t really care about the advertisers, resulting in click fraud, pixel stuffing, ad stacking, and a whole host of questionable behavior that is at best on the edge of legality and absolutely not in the advertisers’ interest.

As with any other company or industry built on fundamentally misaligned incentives, this is unsustainable.

The Imminent Advertiser Exodus

The above graph shows the inefficiency of this arrangement: publishers and ad networks are locked in a dysfunctional relationship that doesn’t serve readers or advertisers, and it’s only a matter of time until advertisers — which again, care only about reaching potential customers, wherever they may be — desert the whole mess entirely for new, more efficient and effective advertising options that put them directly in front of the people they care about. That, first and foremost, is Facebook, but other social networks like Twitter, Snapchat, Instagram, Pinterest, and others will benefit as well:

Notice that none of this depends on the adoption of ad-blockers. Indeed, ad blockers don’t really hurt advertisers that much anyways: an ad that is blocked is one that is not paid for, meaning the pain falls entirely on publishers. But, as I just noted, the truth is that advertising isn’t long for the majority of online publishing anyway.

What Should Publishers Do?

It is easy to feel sorry for publishers: before the Internet most were swimming in money, and for the first few years online it looked like online publications with lower costs of production would be profitable as well. The problem, though, was the assumption that advertising money would always be there, resulting in a “build it and they will come” mentality that focused almost exclusively on content production and far too little on sustainable business models.

In fact, publishers going forward need to have the exact opposite attitude from publishers in the past: instead of focusing on journalism and getting the business model for free, publishers need to start with a sustainable business model and focus on journalism that works hand-in-hand with the business model they have chosen. First and foremost that means publishers need to answer the most fundamental question required of any enterprise: are they a niche or scale business?

- Niche businesses make money by maximizing revenue per user on a (relatively) small user base

- Scale businesses make money by maximizing the number of users they reach

The truth is most publications are trying to do a little bit of everything: gain more revenue per user here, reach more users over there. However, unless you’re the New York Times (and even then it’s questionable), trying to do everything is a recipe for failing at everything; these two strategies require different revenue models, different journalistic focuses, and even different presentation styles:

-

Revenue Models:

- For niche publications, given their need to maximize their revenue per user, the most obvious revenue model is subscriptions. However, niche publications are also a great fit for native advertising; to use a random example, what model railroad company wouldn’t want to place content on the premier model railroad blog? Sure, that may seem impossibly narrow and unscalable, but the point of niches is that while they are likely to be dominated by just one or two publications, there are a massive number of niches in the world, most of which are underserved both from a journalistic standpoint and especially an ad inventory standpoint

- Broad-based publications will obviously be ad-driven; to reach the maximum number of people a publication must be free. However, while broad-based publishers will likely continue to garner as much revenue from their websites as possible, as time goes on more and more revenue is likely to come from places like Facebook’s Instant Articles or the recently-rumored initiative from Google and Twitter to build an open-source alternative 2

-

Journalistic Focuses:

- Niche publications will be extremely focused. The key to earning subscription revenue is to have a highly differentiated product that people are willing to pay for; similarly, the most effective native advertising model is placing content in a feed that people actively seek out and read to completion

- Broad-based publications will be focused on stories that draw maximum interest, clicks, and especially shares. While much of this content will be about entertainment and amusement (the “Lifestyle” section has long been among the most profitable for newspapers) there will also be an incentive to create stories that have a wide-ranging impact

-

Presentation Styles:

- Niche publications will be destination sites: places their readers visit intentionally. To that end it will make sense for niche publications to invest in site design or even per-story design that makes their sites stand out

- Broad-based publications, on the other hand, should focus on keeping their presentation as simple as possible to better enable portability across the various customer touch points. Text and images work everywhere; custom layouts not so much

The key thing about both of these models is that they fix the incentive problem: subscriptions tie niche publications to their readers in about as direct a way as possible, while a native advertising model is effective because, just like the old days, it ensures that the reader and the customer-to-be-reached by the advertiser are one and the same.

As for broad-based publications, keep in mind what advertisers care about: reaching potential customers wherever they may be, which just so happens to be exactly what broad-based publications should do — be everywhere with their content, wherever their potential readers might be. No company has nailed this point like BuzzFeed: indeed, what makes their advertising agency business model so effective is that their editorial and advertising teams do the exact same thing the exact same way. 3

This didn’t happen by accident; to BuzzFeed founder and CEO Jonah Peretti’s credit, BuzzFeed was built from day one to be a business that earned money the old-fashioned way: by being better at what they do than any of their competitors. 4 Publications that seek to imitate their success — and their growth — need to do so not simply by making listicles or by focusing on social. Fundamentally, like BuzzFeed, they need to start with their business model: the future of journalism depends on embracing what far too many journalists are proud to ignore.

Discuss this article on the Stratechery Forum ( members-only )

- Apps can use iOS 9’s new Safari view controller that basically uses Safari as the in-app browser, which would, as expected, utilize an installed and enabled content-blocking extension. 3rd-party Twitter apps Twitterrific and Tweetbot have already instituted the Safari view controller, but it’s unclear if Facebook and the other official social network apps will follow suit; note that Facebook, for example, has yet to institute iOS’s now year-old share sheet because the social network (understandably) prefers to control where content is shared [ ↩ ]

- Or Apple News, another iOS 9 feature. However, I’m a bit skeptical: I think people who will seek out news are the exact types who will have favored publications that are likely to fall under the niche model [ ↩ ]

- The elegance of this business model is why I have called BuzzFeed The Most Important News Organization in the World [ ↩ ]

- Correction: BuzzFeed was an experiment until Peretti left the Huffington Post to make it into a business [ ↩ ]

文章版权归原作者所有。