The IT Era and the Internet Revolution

The IT Era and the Internet Revolution

I like to say that I write about media generally and journalism specifically because the industry is a canary in the coal mine when it comes to the impact of the Internet: text shifted from newsprint to the web seamlessly, completely upending the industry’s business model along the way.

Of course I have a vested interest in this shift: for better or worse I, by virtue of making my living on Stratechery, am a member of the media, and it would be disingenuous to pretend that my opinions aren’t shaped by the fact I have a personal stake in the matter. Today, though, and somewhat reluctantly, I am not just acknowledging my interests but explicitly putting Stratechery forward as an example of just how misguided the conventional wisdom is about the Internet’s long-term impact on society, in ways that extend far beyond newspapers (but per my point, let’s start there).

What Killed Newspapers

On Monday Jack Shafer, the current dean of media critics, asked What If the Newspaper Industry Made a Colossal Mistake? :

What if, in the mad dash two decades ago to repurpose and extend editorial content onto the Web, editors and publishers made a colossal business blunder that wasted hundreds of millions of dollars? What if the industry should have stuck with its strengths — the print editions where the vast majority of their readers still reside and where the overwhelming majority of advertising and subscription revenue come from — instead of chasing the online chimera?

That’s the contrarian conclusion I drew from a new paper written by H. Iris Chyi and Ori Tenenboim of the University of Texas and published this summer in Journalism Practice. Buttressed by copious mounds of data and a rigorous, sustained argument, the paper cracks open the watchworks of the newspaper industry to make a convincing case that the tech-heavy Web strategy pursued by most papers has been a bust. The key to the newspaper future might reside in its past and not in smartphones, iPads and VR. “Digital first,” the authors claim, has been a losing proposition for most newspapers.

Shafer’s theory is that the online editions of newspapers is inferior to print editions; ergo, people read them less. To buttress his point Shafer cites statistics showing that most local residents don’t read their local newspaper online.

The flaw in this reasoning should be obvious to any long-time Stratechery reader : people in the pre-Internet era didn’t read local newspapers because holding an unwieldy ink-staining piece of flimsy newsprint was particularly enjoyable; people read local newspapers because it was the only option. And, by extension, people don’t avoid local newspapers’ websites because the reading experience sucks — although that is true — they don’t even think to visit them because there are far better ways to occupy their finite attention.

Moreover, while some of those alternatives are distractions like games or social networking, any given newspaper’s real competitors are other newspapers and online-only news sites. When I was growing up in Wisconsin I could get the Wisconsin State Journal in my mailbox or I could go to a bookstore to buy the New York Times; it didn’t matter if the latter was “better”, it was too inconvenient for most. Now, though, the only inconvenience is tapping a different app. Of course most readers don’t even bother to do that: they just click on whatever is in their Facebook feed, interspersed with advertisements that are both more targeted and more measurable than newspaper advertisements ever were.

The truth is there is no one to blame for the demise of newspapers — not Google or Facebook, and not 1990s era publishers. The entire linchpin of the newspaper business model was controlling distribution, and when that linchpin was obliterated by the Internet it was inevitable that the entire apparatus would collapse.

The IT Era

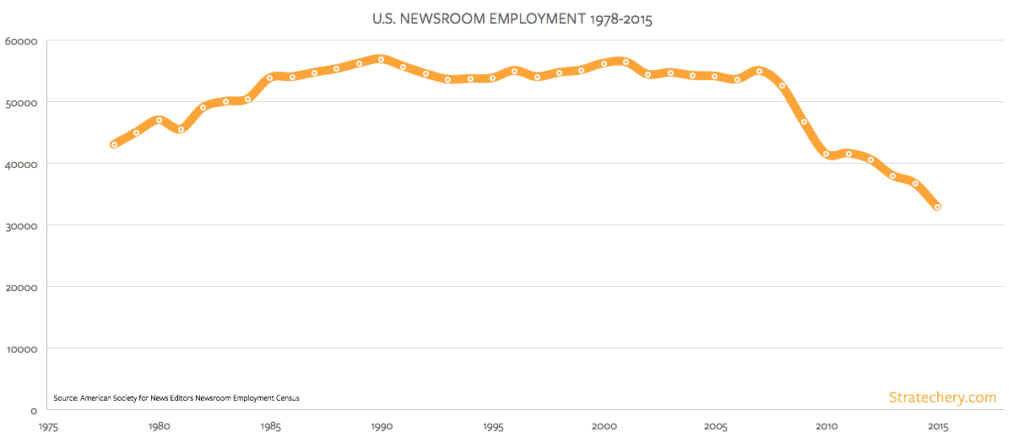

Make no mistake, this sucks for journalists in particular; newsroom employment has plummeted over the last decade:

Still, just for a moment set aside those disappearing jobs and look at what happened from roughly 1985 to 2007: at a time when newspaper revenue continued to grow jobs didn’t grow at all; naturally, newspaper companies were enjoying record profits.

What had happened was information technology: copy could be made on computers, passed on to editors via local area networks, then laid out digitally. It was a massive efficiency improvement over typewriters, halftone negatives, and literal cutting-and-pasting:

Newspapers obviously weren’t the only industry to benefit from information technology: the rise of ERP systems, databases, and personal computers provided massive gains in productivity for nearly all businesses (although it ended up taking nearly a decade for the improvements to show up). What this first wave of information technology did not do, though, was fundamentally change how those businesses worked, which meant nine of the ten largest companies in 1980 were all amongst the 21 largest companies in 1995 1 . The biggest change is that more and more of those productivity gains started accruing to company shareholders, not the workers — and newspapers were no exception.

This is why I believe it is critical to draw a clear line between the IT era and the Internet era: the IT era saw the formation of many still formidable technology companies, but their success was based on entrenching deep-pocketed incumbent enterprises who could use technology to increase the productivity of their workers. What makes the Internet era a much bigger deal is that it challenges the very foundations of those enterprises.

The Internet Revolution

I already explained what happened to newspapers when distribution erased local newspapers moats in the blink of an eye; as I suggested at the beginning, though, this was not an isolated incident but a sign of what was to come. Back in July I laid out how the acquisition of Dollar Shaving Club suggested the same process was happening to consumer packaged goods companies: leveraging size to secure shelf space supported by TV advertising was no longer the only way to compete. A few weeks before that I pointed out that television was intertwined with its advertisers ; the Internet was eroding the business of linear TV, CPG companies, retailers, and even automative companies simultaneously, leaving the entire post World War II economic order dependent on sports to hold everything together.

The ways these changes arrive are strikingly similar; I call it the FANG Playbook after Facebook-Amazon-Netflix-Google:

None of the FANG companies created what most considered the most valuable pieces of their respective ecosystems; they simply made those pieces easier for consumers to access, so consumers increasingly discovered said pieces via the FANG home pages. And, given that Internet made distribution free, that meant the FANG companies were well on their way to having far more power and monetization potential than anyone realized…

By owning the consumer entry point — the primary choke point — in each of their respective industries the FANG companies have been able to modularize and commoditize their suppliers, whether those be publishers, merchants and suppliers, content producers, or basically anyone who needs to be found on the Internet.

This is the critical difference between the IT-era and the Internet revolution: the first made existing companies more efficient, the second, primarily by making distribution free, destroyed those same companies’ business models.

The Internet Upside

What is easy to forget in this tale of woe is that all of these upheavals have massively benefited consumers: that I can read any newspaper in the world is a good thing. That we have access to many more products at much lower price points is amazing. That one can search the entire corpus of human knowledge from just about anywhere in the world, or connect to billions of people, or more prosaically, watch what one wants to watch when one wants to watch it, is pretty great.

Beyond that, what are even more difficult to see are the new possibilities that arise from said upheaval, which is where Stratechery comes in. By no means is this site a replacement for newspapers: I’m pretty explicit about the fact I don’t do original reporting. And yet, I certainly wouldn’t classify the time spent reading this site in the same category as the diversions of gaming and social networking I mentioned earlier. Rather, my goal is to deliver something completely new: deep, ongoing analysis into the business and strategy of technology. It is a viewpoint that wasn’t worth cutting-and-pasting into a broadsheet meant to serve a geographically limited market, but when the addressable market is the entire world the economics suddenly work very well indeed.

Oh, and did you catch that? Saying “the addressable market is the whole world” is the exact same thing as saying that newspapers suddenly had to compete with every other news source in the world; it’s not that the Internet is inherently “good” or “bad”, rather it is a new reality, and just because industries predicated on old assumptions must now fail should not obscure the fact that entirely new industries built with new assumptions — including huge new opportunities for small-scale entrepreneurship by individuals or small teams — are now possible. See YouTube or Etsy or yes, journalism, and this is only the beginning.

The Importance of Secondary Effects

I’d certainly like to think the benefits of this change run deeper than simply ensuring I earn a decent living; it is deeply meaningful to me when I have readers say my writing helped them land a job, or that they are applying my frameworks to a particularly difficult decision they are facing, or even that they feel like they are getting a business school education for practically free. To be certain that last point is overstating things, at least from a business school’s perspective: the breadth of material covered, the degree on your resume, and of course the friends you make are big advantages. But it used to be that the choice was a binary one: spend six figures on business school or don’t; if one can pick up a useful bit of business thinking for $10/month while still being a productive worker then isn’t that a win for society?

These secondary effects will be the key to building a prosperous society amidst the ruin of the Internet’s creative destruction: what is so exciting about Uber is not the fact it is wiping out the taxi industry, but rather that transportation as a service has the potential to radically transform our cities. What happens when parking lots go away, commutes in self-driving cars lend themselves to increased productivity, or going out is as easy as tapping an app? What kind of new jobs and services might arise?

As another example, I wrote last month about the dramatic shift in enterprise software that is being enabled by the cloud. The simple ability to pay-as-you-go has already had a big impact on startups and venture capital , but the initial impact on established companies has been to operationalize costs and increase scalability for established processes; the true transformation — building and selling software in completely new ways — is only getting started. Again, there is a difference between making an existing process more efficient and enabling a completely new approach. The gains from the former are easy to measure; the transformation of the latter is only apparent in retrospect, in part because the old way takes time to die and repurpose.

This two stage process is going to be the most traumatic when it comes to the already-started-and-accelerating introduction of automation and artificial intelligence. The downsides are obvious to everyone: if computers can do the job of a human, then the human no longer has a job. In the long run, though, what might that human do instead? To presume that displaced workers will only ever sit around collecting a universal basic income 2 is to, in my mind, sell short the human drive and ingenuity that has already carried us far from our cavemen ancestors.

I know that my perspective is a privileged one: I am a clear beneficiary of this new world order. Moreover, I know that very good and important things will be lost, at least for a time, in these transitions. I strongly agree with Shafer, for example, that newspapers “still publish a disproportionate amount of the accountability journalism available” and that “we stand to lose one of the vital bulwarks that protect and sustain our culture.”

Fixing that and the many other problems wrought by the Internet, though, requires looking forwards, not backwards. The most fundamental assumptions underlying businesses — critical institutions in any society — have changed irrevocably, and to pretend they haven’t is a colossal mistake.

文章版权归原作者所有。