Intel, Mobileye, and Smiling Curves

Intel, Mobileye, and Smiling Curves

There is a fascinating paragraph in this Wall Street Journal article about Intel’s purchase of Mobileye NV, 1 an Advanced Driver Assistance System primarily focused on camera-based collision avoidance and, going forward, autonomous driving:

The considerable premium Intel is willing to pay for Mobileye reflects the enormous value tech companies see in the automation of cars and trucks, said Mike Ramsay, research director at Gartner Inc. It would have been inconceivable a few years ago — it is more than double what the private-equity firm Cerberus Capital Management LLC paid for Chrysler LLC in 2007.

Chrysler LLC is, of course, a car manufacturer, since merged with Fiat; the price it was sold for is about as relevant to Mobileye as the value of a computer OEM to, well, Intel.

The Smiling Curve and PCs

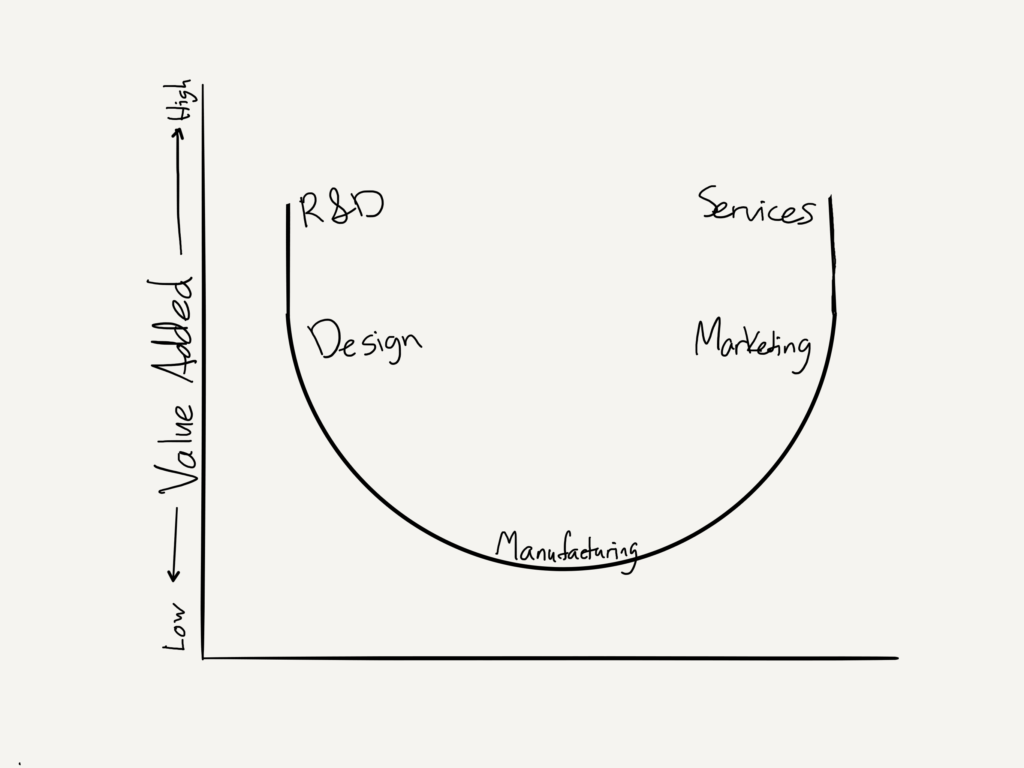

I wrote about The Smiling Curve back in 2014 ; it is a concept that was coined by one of those computer OEMs, Stan Shih of Acer, in the early 1990s, as a means of explaining why Acer needed to change its business model.

Shih explained the curve in his book Me-Too Is Not My Style :

The basic structure of the value-added curve, from left to right on the horizontal axis, are the upper, middle and down stream of an industry, that is, the component production, product assembly and distribution. The vertical axis represents the level of value-added. In terms of market competition type, the left side of the curve is worldwide competition whose success depends on technology, manufacturing and economy of scales. On the right side of the curve is regional competition. Its success depends on brand name, marketing channel and logistic capability.

Every industry has its own value-added curve. Different curves are derived according to different levels of value-added. The major factors in determining the level of value-added are entry barrier and accumulation of capability. In other words, with a higher entry barrier and greater accumulation of capabilities, the value-added will be higher.

Take the computer industry as an example. Microprocessor manufacturing or the establishment of brand name business comes with a higher entry barrier, and requires many years of strength accumulation to achieve progress. However, computer assembly is very easy. That is why no-brand computers are found everywhere in electronic shopping malls.

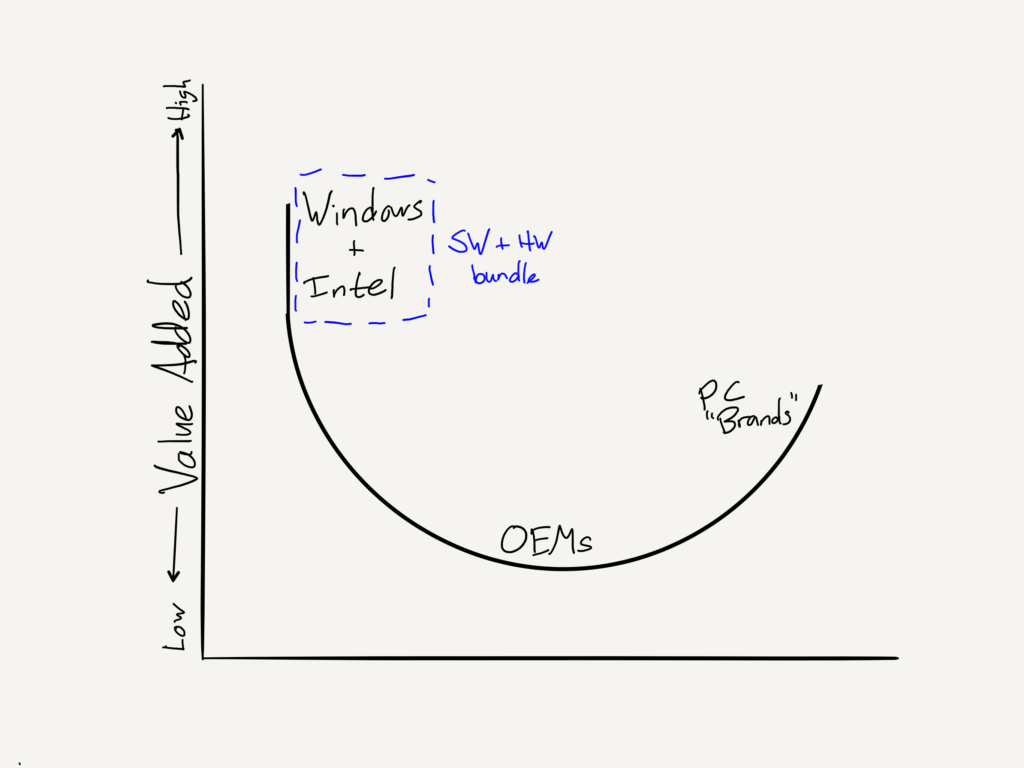

When Shih coined the concept in 1992, “microprocessor manufacturing” meant Intel: outside of the occasional challenge from AMD, Intel provided one of two parts (along with Windows) of the personal computer that couldn’t be bought elsewhere; the result was one of the most profitable companies of all time.

Note, though, that while a core piece of Intel’s competitive advantage (particularly relative to AMD) was, as Shih noted, the entry barrier of fabrication, Intel’s close connection to Windows — to software — was just as critical. It is operating systems that provide network effects and the tremendous profitability that follows, and operating systems are based on software. In other words, the PC smiling curve looked more like this:

Windows and x86 processors were effectively a bundle, and Microsoft and Intel split the profits. Remember, bundling is how you make money , and in this case Intel-based hardware provided Microsoft a vehicle to profit from licensing Windows, while Windows built an unassailable moat for both — at least in PCs.

The Smiling Curve and Phones

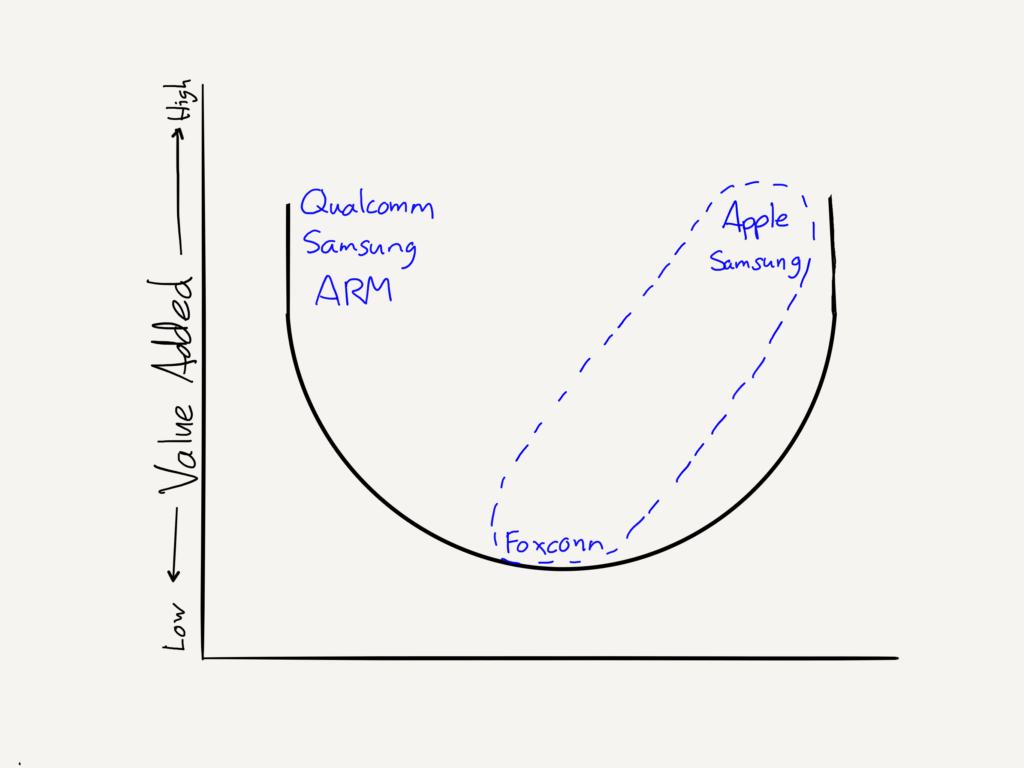

Obviously things went much differently for both Microsoft and Intel — and Acer — when it came to smartphones. The overall structure of the industry still fit the smiling curve, but the software was layered on completely differently:

Apple used software to bundle together manufacturing (done under contract) and the final product marketed to consumers; over time the company also added components, specifically microprocessors, to the bundle (also built under contract). The result was the most successful product of all time .

Google, meanwhile, made Android free; the bundle, such as there was, was between the operating system and Google’s cloud. The rest of the ecosystem was left to fight it out: distribution and marketing helped Samsung profit on the right, while R&D and manufacturing prowess meant profits for ARM, Samsung, and Qualcomm, along with a host of specialized component suppliers, on the left. Still, no one was as profitable as Intel was in the PC era, because no one had the software bundle.

That said, the role of software was critical: Intel, for example, started out the smartphone race at a performance disadvantage; while the company caught up the ecosystems had already moved on, because too much software was incompatible with x86.

The Smiling Curve and Servers

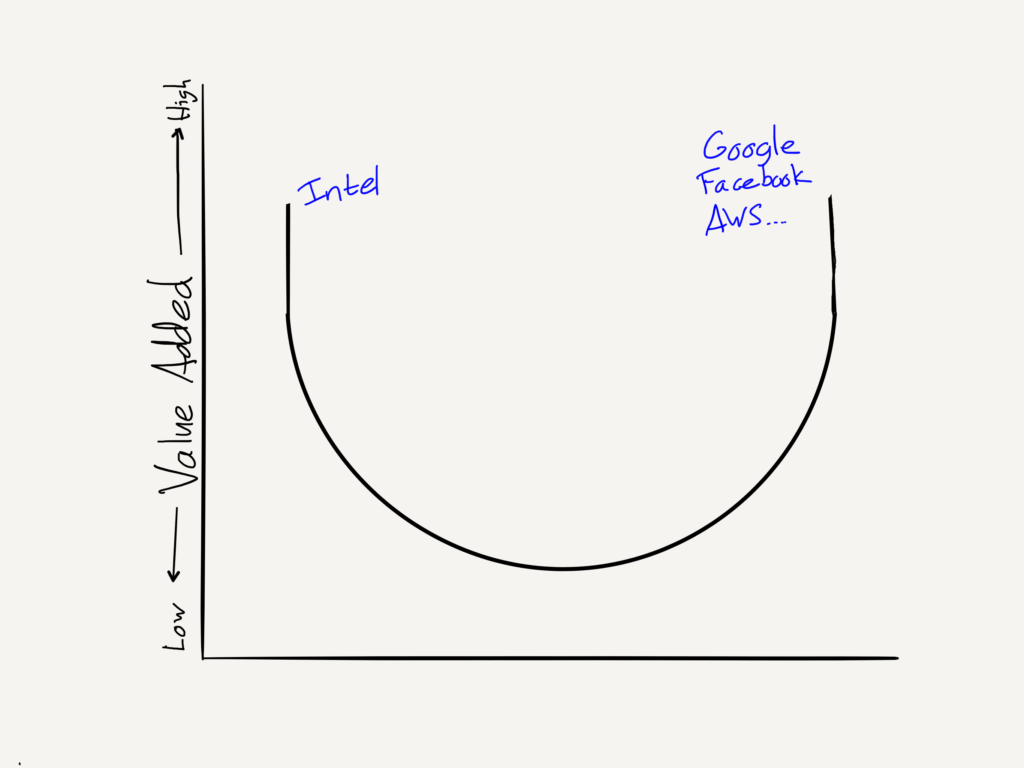

Intel has done better in the cloud:

The cloud took the commodification wave that hit PCs to a new extreme: major cloud providers, armed with massive scale and their own reference designs, hired Asian manufacturers directly. The one exception was Intel and its Xeon chips (which themselves undercut purpose-built server processors from companies like Sun and IBM), which continue to be the most important contributors to Intel’s bottom-line. 2 Still, the real value in the cloud is on the right, where the software is: Facebook, Google, AWS.

Cars and the Future

A little over a year ago I explained in Cars and the Future that there were three changes happening in the personal transportation industry simultaneously:

- Drivetrains were changing from the internal combustion engine to electric

- Car operation was moving from human-based to computer-based (i.e. self-driving cars)

- Ownership was shifting from individuals to fleets, dispatched by ride-sharing services

As I noted in that piece each of these developments is in some respects independent of the other:

- Tesla has led the way in electric vehicles, building an amazing brand along the way, but traditional car companies are not far behind. That’s because the drivetrain is a sustaining technology, not a disruptive one: the business model is by and large the same. 3

文章版权归原作者所有。