Data Factories

Data Factories

I’m generally annoyed by the cliché “If you’re not paying you’re the product”; Derek Powazek has explained why the implications of this statement are usually misleading and often wrong, something that is particularly problematic in the context of Aggregators . After all, if a company’s market power flows from controlling demand — that is, users — that means said company is incentivized to keep those users satisfied; it is suppliers that have to “take it or leave it”.

This explains why the idea of an Aggregator being a monopoly is hard to get one’s head around; in the physical world where market power comes from controlling distribution — think AT&T, or your local cable company, or a utility company — there is no incentive to treat end users well, because users have no choice in the matter. On the Internet, though, where distribution is effectively free, alternatives are only a click away; Aggregators are extremely motivated to make sure that click doesn’t happen, which means giving the users what they want (the technical term is “increasing engagement”). Users are a priority, not a product.

And yet, as is so often the case, clichés persist because there is some truth to them. Facebook and Google — the two Super Aggregators — make money through ads, and advertisers come to Facebook and Google because they want to reach consumers. From an advertiser perspective users — or to be more precise, access to users’ attention — is a product they are absolutely paying for.

Views on Facebook

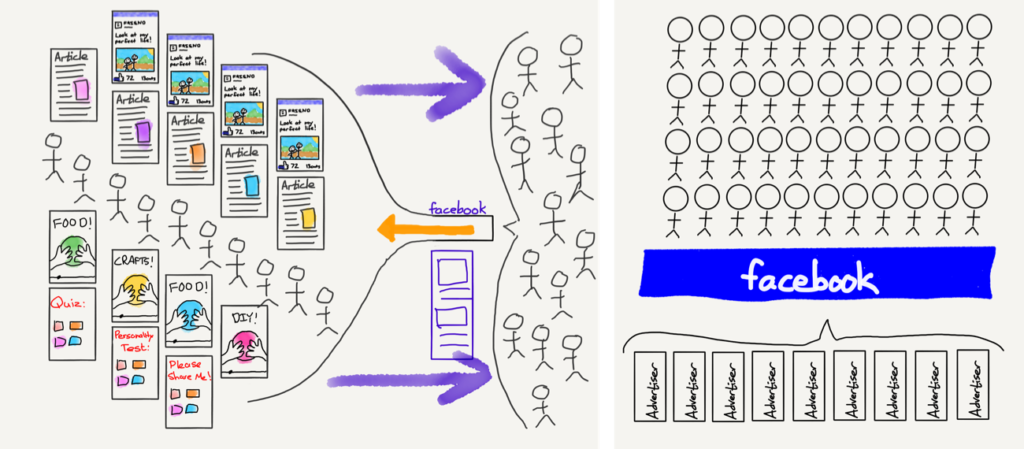

This seeming dichotomy — prioritizing users on one hand, and selling access to their attention on the other — makes more sense if you first think of Super Aggregators as two distinct businesses: Aggregator and advertising-seller. To use Facebook as an example (as I will for the rest of the article, although nearly everything applies to Google as well), it is both an Aggregator that content providers clamor to reach, as well as the gatekeeper for consumers advertisers wish to sell to:

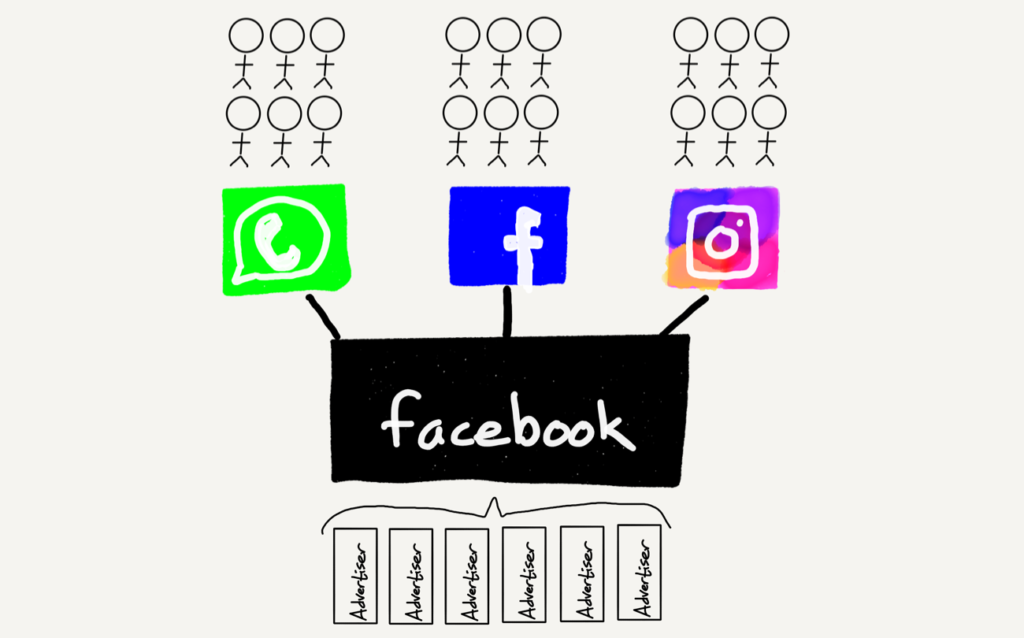

Still, this isn’t quite right, because Facebook the company is not simply the so-called “Blue App” but also several other businesses, most notably Instagram and WhatsApp (there is also Messenger, but given its user-facing network is the same as the Blue App I don’t really consider it to be distinct). Once you add those to the mix Facebook the company looks like this:

You’ll note that I’ve taken to using the term “Blue App” to distinguish Facebook the network from Facebook the company; the question, though, is what exactly is the company anyways?

The Data Factory

At a superficial level, Facebook is a sort of holding company for social networks; back in 2014 I called it The Social Conglomerate . That, though, is very much a user-centric perspective; to that end, if you consider the advertising perspective, you could argue that Facebook the company is an advertising dashboard and sales force.

I think, though, that sells short the functionality of Facebook the company. Specifically, Facebook is a data factory. Wikipedia defines a factory thusly:

A factory or manufacturing plant is an industrial site, usually consisting of buildings and machinery, or more commonly a complex having several buildings, where workers manufacture goods or operate machines processing one product into another.

Facebook quite clearly isn’t an industrial site (although it operates multiple data centers with lots of buildings and machinery), but it most certainly processes data from its raw form to something uniquely valuable both to Facebook’s products (and by extension its users and content suppliers) and also advertisers (and again, all of this analysis applies to Google as well):

- Users are better able to connect with others, find content they are interested in, form groups and manage events, etc., thanks to Facebook’s data.

- Content providers are able to reach far more readers than they would on their own, most of whom would not even be aware those content providers exist, much less visit of their own volition.

- Advertisers are able to maximize the return on their advertising dollar by only showing ads to individuals they believe are predisposed to like their product, making it more viable than ever before to target niches (to the benefit of their customers as well).

And then, in exchange for these benefits that derive from data, Facebook sucks in data from all three entities:

- Users provide Facebook with data directly, both through information and media they upload, and also through their actions on Facebook properties.

- Content is not simply data in its own right, but also a catalyst for generating user action data.

- Advertisers, like content providers, not only provide data in its own right, which acts as a catalyst for generating user action data, but also upload huge amounts of data directly in order to better target prospective customers.

Those aren’t the only avenues through which Facebook collects data: the company has deals with multiple third-party data collection companies, gathering everything from web traffic to offline store receipts, and also has incentivized an untold number of websites — particularly content providers — to include Facebook links on their sites that collect data from those sites.

That results in a much fuller picture of Facebook’s business:

Data comes in from anywhere, and value — also in the form of data — flows out, transformed by the data factory.

Regulating the Internet

Two weeks ago, in The European Union Versus the Internet , I argued that effective regulation of tech companies, particularly Super Aggregators like Facebook and Google, had to work with the fundamental principles of the Internet, not against them; otherwise, the likely outcome would be to entrench these Internet giants with little gain to consumers.

First and foremost regulators need to understand that the power of Aggregators comes from controlling demand, not supply. Specifically, consumers voluntarily use Google and Facebook, and “suppliers” like content providers, advertisers, and users themselves, have no choice but to go where consumers are. To that end:

Facebook’s ultimate threat can never come from publishers or advertisers, but rather demand — that is, users. The real danger, though, is not from users also using competing social networks (although Facebook has always been paranoid about exactly that); that is not enough to break the virtuous cycle. Rather, the only thing that could undo Facebook’s power is users actively rejecting the app. And, I suspect, the only way users would do that en masse would be if it became accepted fact that Facebook is actively bad for you — the online equivalent of smoking.

For Facebook, the Cambridge Analytica scandal was akin to the Surgeon General’s report on smoking: the threat was not that regulators would act, but that users would, and nothing could be more fatal. That is because the regulatory corollary of Aggregation Theory is that the ultimate form of regulation is user generated.

If regulators, EU or otherwise, truly want to constrain Facebook and Google — or, for that matter, all of the other ad networks and companies that in reality are far more of a threat to user privacy — then the ultimate force is user demand, and the lever is demanding transparency on exactly what these companies are doing.

What, though, does transparency mean in the context of enabling “user generated regulation”, and what might meaningful regulation look like that achieves the goal of forcing said transparency in a way that fosters competition instead of inhibiting it? The answer goes back to data factories.

Raw Data Versus Processed Data

The first challenge with a data factory is that it is impossible to peer inside. Both Facebook and Google offer customers ways to view their data, but not only is the presentation overwhelming, the data is precisely what you gave them. It is the raw inputs.

Advertisers, interestingly enough, cannot download custom audiences once uploaded, but given that data is (also) their business, it is extremely likely that they retain the list of email addresses they uploaded in the first place; the same thing applies to 3rd party data providers. Websites, meanwhile, are completely in the dark: that Facebook badge or like button may provide a page view or two, but it doesn’t give any data back in return.

What no one gets is the final product: the melding of all that data from all those sources to build a far more detailed profile of every Facebook user than they provided on their own. There is no question, though, that it is happening. Last week Gizmodo had an excellent write-up of a paper in the journal Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies detailing how Facebook users could be targeted for ads with a whole host of information that was never provided by the user, including landline numbers, unpublished email addresses, and phone numbers provided for two-factor authentication:

They found that when a user gives Facebook a phone number for two-factor authentication or in order to receive alerts about new log-ins to a user’s account, that phone number became targetable by an advertiser within a couple of weeks. So users who want their accounts to be more secure are forced to make a privacy trade-off and allow advertisers to more easily find them on the social network. When asked about this, a Facebook spokesperson said that “we use the information people provide to offer a more personalized experience, including showing more relevant ads.” She said users bothered by this can set up two-factor authentication without using their phone numbers; Facebook stopped making a phone number mandatory for two-factor authentication four months ago .

That quote from the spokesperson is an acknowledgement of the data factory: Facebook doesn’t care where it gets data, it is all just an input in service of the output — a targetable profile.

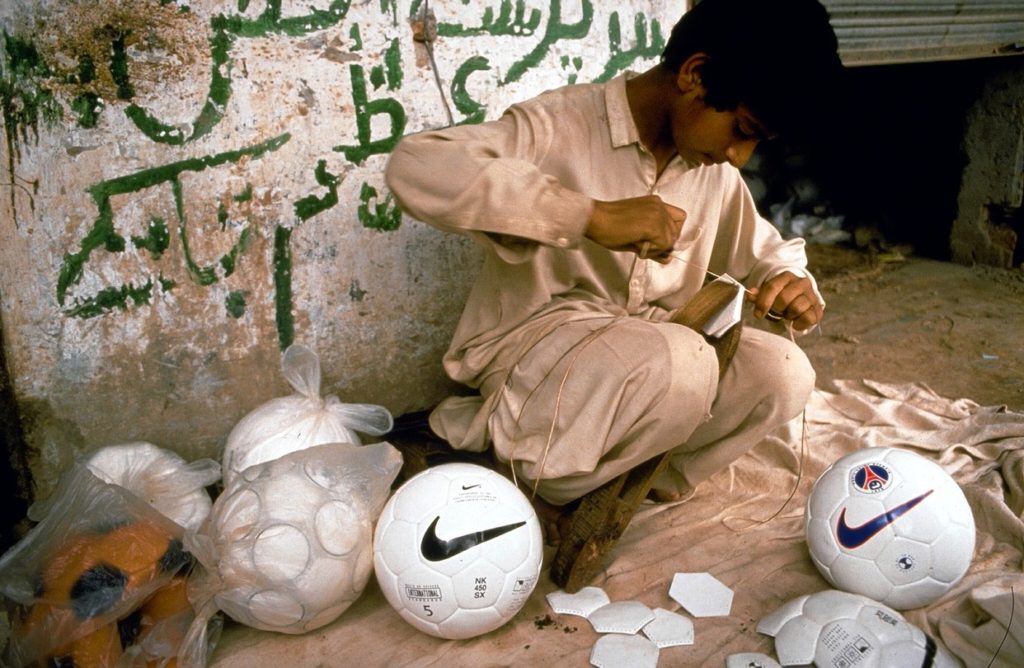

This lack of care about what precisely goes into a finished product is hardly unique to Facebook. One of the most famous examples is Nike:

That image is from the June, 1986, issue of Life Magazine, which detailed how children in Pakistan were manufacturing soccer balls for pennies a day. Nike executives, in a refrain that is vaguely familiar, were initially aggrieved; after all, soccer balls were not inflated until after they were shipped, which meant the photo was staged.

That was surely correct, and yet such a complaint utterly missed the point: Nike didn’t really care where it got its soccer balls, or shoes or clothes or anything else. It simply paid the factory owners and washed its hands of the problem. That photo, and the decades of protests and boycotts that followed, forced the company to do better.

The Privacy Obstacle

Unfortunately, while Nike could not stop a photographer from traveling to Pakistan (and, truth be told, stage a photo), the general public has no way to see inside the Facebook or Google factories — and this is where regulators come in.

The most important thing that regulators could do is force Facebook and Google — and all data collectors — to disclose their factory output. Give users the ability to see not simply what they put in — which again, Google and Facebook do (and which GDPR requires), but also what comes out after all of the inputs are mixed and matched.

Make no mistake, no company will do this on its own, and not simply for business reasons. Note the Facebook spokesman’s response to Gizmodo when asked about the use of uploaded contact information:

“People own their address books,” a Facebook spokesperson said by email. “We understand that in some cases this may mean that another person may not be able to control the contact information someone else uploads about them.”

This gets at how it is privacy regulations in particular go wrong: in the attempt to make rules that protect people without their agency, those wishing to take said agency cannot even know what exactly Facebook knows about them because, well, privacy. Meanwhile, websites throw up pop-ups and overlays that no one reads, or ban entire continents, not because their users care but because a regulator said so.

Privacy Realities

Here is the other reality regulators need to grapple with: most users don’t care about privacy, particularly if it saves them money. I came across this tweet in response to an interview clip of Tim Cook talking about privacy and it rather succinctly made the point:

Frankly, I don’t blame the apathy of most users: what Facebook and Google and all of the other ad-supported services and sites on the Internet provide is immensely valuable. Moreover, I’m the first (and often only!) to defend personalized ads: I think they are a critical component of building a future where anyone can build a niche business thanks to the Internet making the entire world an addressable market — if only they can find their customers.

At the same time, most users truly have no idea what data these companies hold. Might they change their minds if they actually saw the processed data, not simply the raw inputs? I don’t know, but I do think it is their decision to make.

Moreover, establishing clear requirements that users be able to view not only the data they uploaded but their entire processed profile — the output of the data factory — would be far less burdensome to new and smaller companies that seek to challenge these behemoths. Data export controls could be built in from the start, even as they are free to build factories as complex as the big companies they are challenging — or, as a potential selling point, show off that they don’t have a factory at all. This is much easier than trying to abide by rules that apply to every user — whether they want the protection or not — and which were designed with Facebook and Google in mind, not an understaffed startup.

Indeed, that is the crux of the matter: regulators need to trust users to take care of their own privacy, and enable them to do so — and, by extension, create the conditions for users to actually know what is going on with their data. And, if they decide they don’t care, so be it. The market will have spoken, an outcome that should be the regulator’s goal in the first place.

文章版权归原作者所有。