IBM’s Old Playbook

IBM’s Old Playbook

The best way to understand how it is Red Hat built a multi-billion dollar business off of open source software is to start with IBM. Founder Bob Young explained at the All Things Open conference in 2014 :

There is no magic bullet to it. It is a lot of hard work staying up with your customers and understanding and thinking through where are the opportunities. What are other suppliers in the market not doing for those customers that you can do better for them? One of the great examples to give you an idea of what inspired us very early on, and by very early on we’re talking Mark Ewing and I doing not enough business to pay the rent on our apartments, but yet we were paying attention to [Lou Gerstner and] IBM…

Gerstner came into IBM and got it turned around in three years. It was miraculous…Gerstner’s insight was he went around and talked to a whole bunch IBM customers and found out that the customers didn’t actually like any of his products. They were ok, but whenever he would sit down with any given customer there was always someone who did that product better than IBM did…He said, “So why are you buying from IBM?” The customers were saying “IBM is the only technology company with an office everywhere that we do business,” and as a result Gerstner understood that he wasn’t selling products he was selling a service.

He talked about that publicly, and so at Red Hat we go, “OK, we don’t have a product to sell because ours is open source and everyone can use our innovations as quickly as we can, so we’re not really selling a product, but Gerstner at IBM is telling us the customers don’t buy products, they buy services, things that make themselves more successful.” And so that was one of our early insights into what we were doing was this idea that we were actually in the services business, even back when we were selling shrink-wrapped boxes of Linux, we saw that as an interim step to getting us big enough that we could sign service contracts with real customers.

Yesterday Young’s story came full circle when IBM bought Red Hat for $34 billion, a 60% premium over Red Hat’s Friday closing price. IBM is hoping it too to can come full circle: recapture Gerstner’s magic, which depended not only on his insight about services, but also a secular shift in enterprise computing.

How Gerstner Transformed IBM

I’ve written previously about Gerstner’s IBM turnaround in the context of Satya Nadella’s attempt to do the same at Microsoft, and Gerstner’s insight that while culture is extremely difficult to change, it is impossible to change nature. From Microsoft’s Monopoly Hangover :

The great thing about a monopoly is that a company can do anything, because there is no competition; the bad thing is that when the monopoly is finished the company is still capable of doing anything at a mediocre level, but nothing at a high one because it has become fat and lazy. To put it another way, for a former monopoly “big” is the only truly differentiated asset. This was Gerstner’s key insight when it came to mapping out IBM’s future…In Gerstner’s vision, only IBM had the breadth to deliver solutions instead of products.

A strategy predicated on providing solutions, though, needs a problem, and the other thing that made Gerstner’s turnaround possible was the Internet. By the mid-1990s businesses were faced with a completely new set of technologies that were nominally similar to their IT projects of the last fifteen years, but in fact completely different. Gerstner described the problem/opportunity in Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance :

If the strategists were right, and the cloud really did become the locus of all this interaction, it would cause two revolutions — one in computing and one in business. It would change computing because it would shift the workloads from PCs and other so-called client devices to larger enterprise systems inside companies and to the cloud — the network — itself. This would reverse the trend that had made the PC the center of innovation and investment — with all the obvious implications for IT companies that had made their fortunes on PC technologies.

Far more important, the massive, global connectivity that the cloud depicted would create a revolution in the interactions among millions of businesses, schools, governments, and consumers. It would change commerce, education, health care, government services, and on and on. It would cause the biggest wave of business transformation since the introduction of digital data processing in the 1960s…Terms like “information superhighway” and “e-commerce” were insufficient to describe what we were talking about. We needed a vocabulary to help the industry, our customers, and even IBM employees understand that what we saw transcended access to digital information and online commerce. It would reshape every important kind of relationship and interaction among businesses and people. Eventually our marketing and Internet teams came forward with the term “e-business.”

Those of you my age or older surely remember what soon became IBM’s ubiquitous ‘e’:

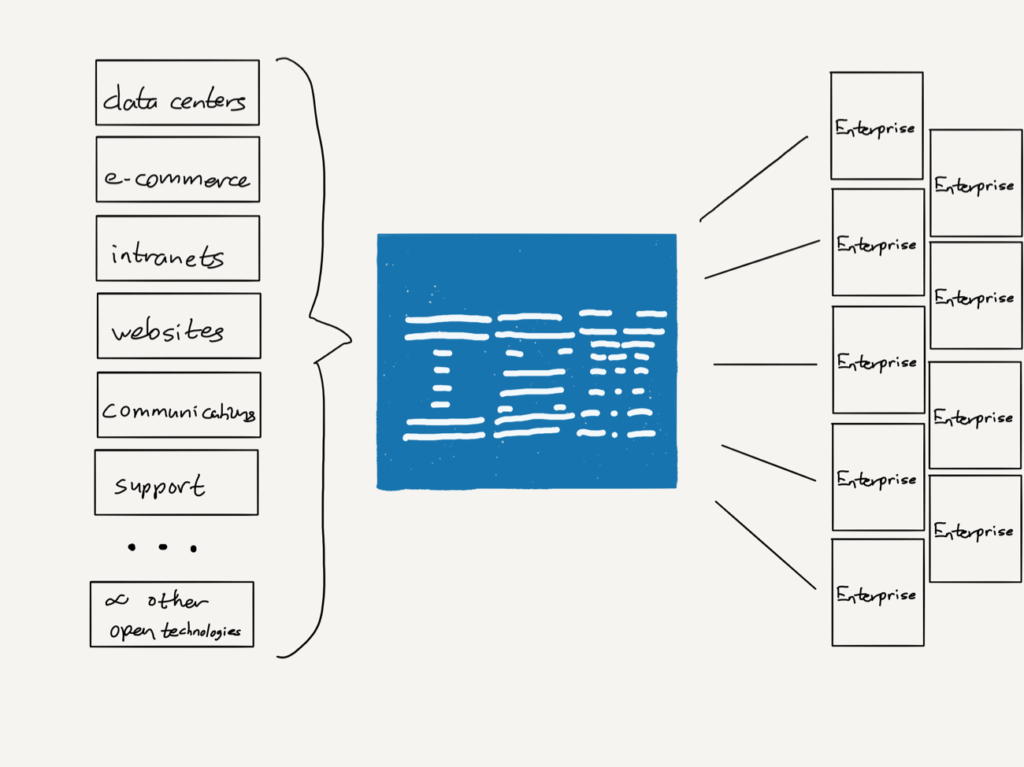

IBM went on to spend over $5 billion marketing “e-business”, an investment Gerstner called “one of the finest jobs of brand positions I’ve seen in my career.” It worked because it was true: large enterprises, most of which had only ever interacted with customers indirectly through a long chain of wholesalers and distributors and retailers suddenly had the capability — the responsibility, even — of interacting with end users directly. This could be as simple as a website, or e-commerce, or customer support, not to mention the ability to tap into all of the other parts of the value chain in real-time. The technology challenges and the business possibilities — the problem set, if you will — were immense, and Gerstner positioned IBM as the company that could solve these new problems.

It was an attractive proposition for nearly all non-tech companies: the challenge with the Internet in the 1990s was that the underlying technologies were so varied and quite immature; different problem spaces had different companies hawking products, many of them startups with no experience working with large enterprises, and even if they had better products no IT department wanted to manage and integrate a multitude of vendors. IBM, on the other hand, offered the proverbial “one throat to choke”; they promised to solve all of the problems associated with this new-fangled Internet stuff, and besides, IT departments were familiar and comfortable with IBM.

It was also a strategy that made sense in its potential to squeeze profit out of the value chain:

The actual technologies underlying the Internet were open and commoditized, which meant IBM could form a point of integration and extract profits, which is exactly what happened: IBM’s revenue and growth increased steadily — often rapidly! — over the next decade, as the company managed everything from datacenters to internal networks to external websites to e-commerce operations to all the middleware that tied it together (made by IBM, naturally, which was where the company made most of its profits). IBM took care of everything, slowly locking its customers in, and once again grew fat and lazy.

When IBM Lost the Cloud

In the final paragraph of Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance? Gerstner wrote of his successor Sam Palmisano:

I was always an outsider. But that was my job. I know Sam Palmisano has an opportunity to make the connections to the past as I could never do. His challenge will be to make them without going backward; to know that the centrifugal forces that drove IBM to be inward-looking and self-absorbed still lie powerful in the company.

Palmisano failed miserably, and there is no greater example than his 2010 announcement of the company’s 2015 Roadmap , which was centered around a promise of delivering $20/share in profit by 2015. Palmisano said at the time:

[The consensus view is that] product cycles will drive industry growth. The industry is consolidating and at the end of the day consumer technology will obliterate all computer science over the last 20 years. I’m an East Coast guy. We’re going to have a slightly different view. Product cycles aren’t going to drive sustainable growth. Clients in the future will demand quantifiable returns on their investment. They are not going to buy fashion and trends. Enterprise will have its own unique model. You can’t do what we’re doing in a cloud.

Amazon Web Services, meanwhile, had launched a full four years and two months before Palmisano’s declaration; it was the height of folly to not simply mock the idea of the cloud, but to commit to a profit number in the face of an existential threat that was predicated on spending absolutely massive amounts of money on infrastructure. 1

文章版权归原作者所有。