The China Cultural Clash

The China Cultural Clash

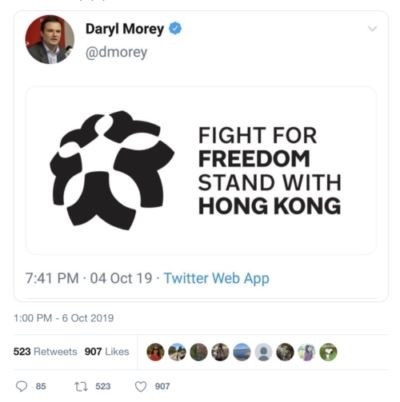

It all started with a tweet:

“It” refers to the current imbroglio surrounding Daryl Morey, the General Manager for the Houston Rockets of the National Basketball Association (NBA), and the latter’s dealings with China. The tweet, a reference to the ongoing protests in Hong Kong, 1 “hurt the feelings of the Chinese people” (a rather frequent occurrence ). The Global Times, a Chinese government-run English-language newspaper, stated in an editorial :

Daryl Morey, general manager of the NBA team the Houston Rockets, has obviously gotten himself into trouble. He tweeted a photo saying “fight for freedom, stand with Hong Kong” on Saturday while accompanying his team in Tokyo. The tweet soon set the team’s Chinese fans ablaze. It can be imagined how Morey’s tweet made them disappointed and furious. Shortly afterward, CCTV sports channel and Tencent sports channel both announced they would suspend broadcasting Rockets’ games. Some of the team’s Chinese sponsors and business partners also started to suspend cooperation with the Rockets.

There’s one rather glaring hole in this story of immediate outrage from Chinese fans over Morey’s tweet: Twitter is banned in China.

China Started It

Earlier this year I wrote about the uneven playing field between the U.S. and China when it comes to technology companies. From China, Leverage, and Values :

This is where I take the biggest issue with Culpan labeling this past week’s actions as the start of a tech cold war: China took the first shots, and they took them a long time ago. For over a decade U.S. services companies have been unilaterally shut out of the China market, even as Chinese alternatives had full reign, running on servers built with U.S. components (and likely using U.S. intellectual property)…

The truth is that the U.S. China relationship has been extremely one-sided for a very long time now: China buys the hardware it needs, and keeps all of the software opportunities for itself — and, of course, pursues software opportunities abroad.

This understated the case: not only were Chinese companies allowed into the U.S. while U.S. companies remained locked out of China, Chinese attacks on U.S. tech companies were allowed by China’s censors, and in fact even augmented by the Great Firewall. James Griffiths wrote about the 2015 attack on Github earlier this year :

In a paper coauthored with researchers at Citizen Lab, an activist and research group at the University of Toronto, Weaver described a new Chinese cyberweapon that he dubbed the “Great Cannon.” The “Great Firewall” — an elaborate scheme of interrelated technologies for censoring internet content coming from outside China—was already well-known. Weaver and the Citizen Lab researchers found that not only was China blocking bits and bytes of data that were trying to make their way into China, but it was also channeling the flow of data out of China.

Whoever was controlling the Great Cannon would use it to selectively insert malicious JavaScript code into search queries and advertisements served by Baidu, a popular Chinese search engine. That code then directed enormous amounts of traffic to the cannon’s targets…The cannon could also be used for other malware attacks besides denial-of-service attacks. It was a powerful new tool: “Deploying the Great Cannon is a major shift in tactics, and has a highly visible impact,” Weaver and his coauthors wrote.

The attack went on for days. The Citizen Lab team said they were able to observe its effects for two weeks after GitHub’s alarms first went off. Afterward, as the GitHub developers struggled to make sense of the attack and come up with a road map for future incidents, there was confusion within the cybersecurity community. Why had China launched so public an attack, in such a blunt fashion? “It was overkill,” Weaver told me. “They kept the attack going long after it had ceased working.”

It was a message: a shot across the bow from the architects of the Great Firewall, who—having conquered the internet at home—were now increasingly taking aim overseas, unwilling to brook challenges to their system of control and censorship, no matter where they came from.

The projects China was presumably targeting were Chinese versions of GreatFire.org, which documents censorship by the Great Firewall, and the New York Times, both of which were hosted on Github. Given the importance of Github to software development, China could not block the site completely, so instead they tried to hold it hostage. It was a harbinger of what happened this week.

Dreams Versus Reality

The story about engagement with China, both in terms of the U.S. generally but also tech specifically, has long been a belief that some engagement was better than no engagement, and that the shift to more freedom was inevitable. President Bill Clinton stated when the U.S. established Permanent Normal Trade Relations with China:

The change this agreement can bring from outside is quite extraordinary, but I think you could make an argument that it will be nothing compared to the changes that this agreement will spark from the inside out in China. By joining the W.T.O., China is not simply agreeing to import more of our products; it is agreeing to import one of democracy’s most cherished values: economic freedom. The more China liberalizes its economy, the more fully it will liberate the potential of its people — their initiative, their imagination, their remarkable spirit of enterprise.

He added with regards to the Internet:

In the new century, liberty will spread by cell phone and cable modem. In the past year, the number of Internet addresses in China has more than quadrupled, from 2 million to 9 million. This year the number is expected to grow to over 20 million. When China joins the W.T.O., by 2005 it will eliminate tariffs on information technology products, making the tools of communication even cheaper, better, and more widely available. We know how much the Internet has changed America, and we are already an open society. Imagine how much it could change China.

Now there’s no question China has been trying to crack down on the Internet. Good luck! That’s sort of like trying to nail jello to the wall. But I would argue to you that their effort to do that just proves how real these changes are and how much they threaten the status quo. It’s not an argument for slowing down the effort to bring China into the world, it’s an argument for accelerating that effort. In the knowledge economy, economic innovation and political empowerment, whether anyone likes it or not, will inevitably go hand in hand.

In fact, it turned out that China was able to first contain the Internet, blocking sites outside the Great Firewall, then control the Internet, censoring content on social networks like Weibo and WeChat, and, as this New York Times article explains , even leverage the Internet:

The Communist Party indeed doesn’t hesitate to use state power to tell the Chinese people how they should think. But the displays of patriotism, especially from young people, also show that the party’s propaganda machine has mastered the power of symbol and symbolism in the mass media and social media era…While imposing tight censorship, the Communist Party has also learned to lean on the most popular artists and the most experienced internet companies to help it instill Chinese with patriotic zeal. It’s propaganda for the Instagram age, if Instagram were allowed in China.

The problem from a Western perspective is that the links Clinton was so sure would push in only one direction — towards political freedom — turned out to be two-way streets: China is not simply resisting Western ideals of freedom, but seeking to impose their own. Note this statement from state-owned broadcast CCTV, as it announced that it would not televise NBA games:

NBA Commissioner Adam Silver defended Morey. “I think as a values-based organization that I want to make it clear…that Daryl Morey is supported in terms of his ability to exercise his freedom of expression,” Silver said in an interview with Kyodo News in Tokyo Japan. CCTV did not agree with Silver’s remarks.

“We are strongly dissatisfied and we oppose Silver’s claim to support Morey’s right of free expression. We believe that any speech that challenges national sovereignty and social stability is not within the scope of freedom of speech,” CCTV said in its statement in Chinese, which was translated by CNBC.

The lever for this rather radical definition of “freedom of speech” is the China market. The Global Times editorial I linked to above could not have been more explicit on this point:

Respecting customers is a universal business rule. Morey has to choose between safeguarding his individual freedom of speech and protecting the Rockets’ commercial interests by respecting the feelings of Chinese fans. When he opted for the former, the Rockets will have to make a second choice from the perspective of the team.

In other words, Morey, a private U.S. citizen posting an image on a social network already banned in China, had to be fired, or the Rockets and the NBA would quite literally pay the price. Abide by China’s standards, or else.

The TikTok Question

China’s exportation of its standards goes beyond brute force. Consider TikTok, the short-form video app owned by the $75 billion Chinese startup ByteDance, which has exploded onto Western markets over the last year. The Guardian reported last last month:

TikTok, the popular Chinese-owned social network, instructs its moderators to censor videos that mention Tiananmen Square, Tibetan independence, or the banned religious group Falun Gong, according to leaked documents detailing the site’s moderation guidelines. The documents, revealed by the Guardian for the first time, lay out how ByteDance, the Beijing-headquartered technology company that owns TikTok, is advancing Chinese foreign policy aims abroad through the app.

The revelations come amid rising suspicion that discussion of the Hong Kong protests on TikTok is being censored for political reasons: a Washington Post report earlier this month noted that a search on the site for the city-state revealed “barely a hint of unrest in sight”.

In fact, at least as of this afternoon, there is a hint of unrest on the site: while searches for “Hong Kong” show city views and high school students playing along with the latest TikTok meme, searching for Hong Kong in Chinese (香港) brings up a video that shows the protestors as hooligans and vandals (this was the first result as of this afternoon, and the only video relating to the protests):

There appear to be similar efforts in the case of the NBA controversy. Searching for the “Warriors”, “Lakers”, and “Rockets” brings up the sort of content you would expect:

However, searching for the same team names in Chinese (“勇士”, “湖人”, and “火箭”, respectively) shows basketball-related results for the first two and nothing related for the third:

This should raise serious concern in the United States and other Western countries: is it at all acceptable to have a social network that has a demonstrated willingness to censor content under the control of a country that has clearly different views on what constitutes free speech?

There is an established route for undoing this state of affairs: earlier this summer China’s Kunlun Tech Company agreed to divest Grindr under pressure from the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS); Kunlun Tech had acquired Grindr without undergoing CFIUS review. TikTok similarly acquired Musical.ly without oversight and relaunched it as TikTok for the Western market; it is worth at least considering the possibility of a review given TikTok’s apparent willingness to censor content for Western audiences according to Chinese government wishes.

The NBA’s Example

Adam Silver, the commissioner of the NBA, ultimately did do the right thing. In response to that CCTV cancellation Silver released a new statement that stated :

Values of equality, respect and freedom of expression have long defined the NBA — and will continue to do so. As an American-based basketball league operating globally, among our greatest contributions are these values of the game¬

It is inevitable that people around the world — including from America and China — will have different viewpoints over different issues. It is not the role of the NBA to adjudicate those differences. However, the NBA will not put itself in a position of regulating what players, employees and team owners say or will not say on these issues. We simply could not operate that way.

Silver added in a press conference following the statement:

Part of the reason I issued the statement I did is because this afternoon, CCTV announced that because of my remarks supporting Daryl Morey’s freedom of expression, not the substance of this statement but his freedom of expression, they were no longer going to air the Lakers-Nets preseason games that are scheduled for later this week. Again, it’s not something we expected to happen. I think it’s unfortunate. But if that’s the consequence of us adhering to our values, we still feel it’s critically important we adhere to those values.

I am increasingly convinced this is the point every company dealing with China will reach: what matters more, money or values?

China Responses

I am not particularly excited to write this article. My instinct is towards free trade, my affinity for Asia generally and Greater China specifically, my welfare enhanced by staying off China’s radar. And yet, for all that the idea of being a global citizen is an alluring concept and largely my lived experience, I find in situations like this that I am undoubtedly a child of the West. I do believe in the individual, in free speech, and in democracy, no matter how poorly practiced in the United States or elsewhere. And, in situations like this weekend, when values meet money, I worry just how many companies are capable of choosing the former?

The NBA, to its immense credit, appears to have done just that. Will technology companies be so brave? Certainly Google did so once before, exiting China in 2010 (albeit after both losing share to Baidu and being attacked by Chinese hackers). At the same time, the company appeared eager to reverse its decision, only terminating “Project Dragonfly” earlier this year; similarly, Facebook worked earnestly for approval — its product team built a censorship apparatus and CEO Mark Zuckerberg learned Chinese — only to give up last year. Both decisions appear motivated by the certainty of failure as opposed to core values.

And then there is Apple: the company is deeply exposed to China both in terms of sales and especially when it comes to manufacturing. The reality is that, particularly when it comes to the latter, Apple doesn’t have anywhere else to go. That, though, is where the company’s massive cash stockpile and ability to generate more comes in handy: it is past time for the company to start spending heavily to build up alternatives. Sticking one’s corporate head in the sand, praying that President Trump will not be re-elected and that everything will go back to normal, is deeply irresponsible both to shareholders and to the values Apple claims motivates them.

The government response is also critical: I already argued that CFIUS should revisit TikTok’s acquisition of Musical.ly; the current skepticism around all Chinese investment in the United States should be continued if not increased. Attempts by China to leverage market access into self-censorship by U.S. companies should also be treated as trade violations that are subject to retaliation. Make no mistake, what happened to the NBA this weekend is nothing new: similar pressure has befallen multiple U.S. companies, often about content that is outside of China’s borders (Taiwan and Hong Kong, for example, being listed in drop-down menus for hotels or airlines).

The biggest, shift, though, is a mindset one. First, the Internet is an amoral force that reduces friction, not an inevitable force for good. Second, sometimes different cultures simply have fundamentally different values. Third, if values are going to be preserved, they must be a leading factor in economic entanglement, not a trailing one. This is the point that Clinton got the most wrong: money, like tech, is amoral. If we insist it matters most our own morals will inevitably disappear.

I wrote a follow-up to this article in this Daily Update .

- This post is not about the specific issues driving the Hong Kong protests; it is useful to understand that China, particularly internally, has characterized the protests, which began when the Hong Kong government attempted to pass an extradition bill that would allow extradition to China, as a separatist movement driven by foreign powers. The protesters state their goals are not independence but rather that China honor its promises surrounding the transfer of Hong Kong back to Chinese rule, particularly in terms of universal suffrage [ ↩ ]

文章版权归原作者所有。