Zero Trust Information

Zero Trust Information

Yesterday Google ordered its entire North American staff to work from home as part of an effort to limit the spread of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that leads to COVID-19. It is an appropriate move for any organization that can do so; furthermore, Google, along with the other major tech companies , also plans to pay its army of contractors that normally provide services for those employees.

Google’s larger contribution, though, happened five years ago when the company led the move to zero trust networking for its internal applications, which has been adopted by most other tech companies in particular. While this wasn’t explicitly about working from home, it did make it a lot easier to pull off on short notice.

Zero Trust Networking

In 1974 Vint Cerf, Yogen Dalal, and Carl Sunshine published a seminal paper entitled “Specification of Internet Transmission Control Program”; it was important technologically because it laid out the specifications for the TCP protocol that undergirds the Internet, but just as notable, at least from a cultural perspective, is that it coined the term “Internet.” The name feels like an accident; most of the paper refers to the “internetwork” Transmission Control Program and “internetwork” packets, which makes sense: networks already existed, the trick was figuring out how to connect them together.

Networks came first commercially as well. In the 1980s Novell created a “network operating system” that consisted of local servers, ethernet cards, and PC software, to enable local area networks that ran inside of large corporations, enabling the ability to share files, printers, other resources. Novell’s position was eventually undermined by the inclusion of network functionality in client operating systems, commoditized ethernet cards, channel mismanagement, and a full-on assault from Microsoft, but the model of the corporate intranet enabling shared resources remained.

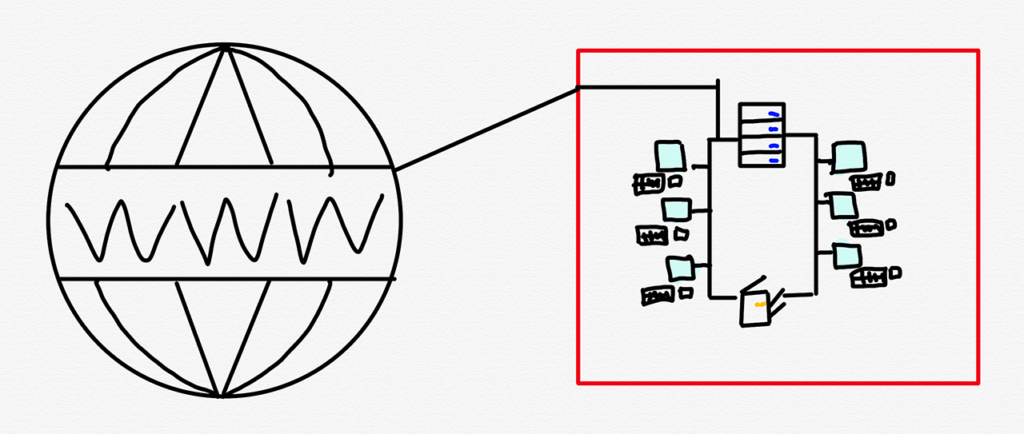

The problem, though, was the Internet: connecting any one computer on the local area network to the Internet effectively connected all of the computers and servers on the local area network to the Internet. The solution was perimeter-based security, aka the “castle-and-moat” approach: enterprises would set up firewalls that prevented outside access to internal networks. The implication was binary: if you were on the internal network, you were trusted, and if you were outside, you were not.

This, though, presented two problems: first, if any intruder made it past the firewall, they would have full access to the entire network. Second, if any employee were not physically at work, they were blocked from the network. The solution to the second problem was a virtual private network, which utilized encryption to let a remote employee’s computer operate as if it were physically on the corporate network, but the larger point is the fundamental contradiction represented by these two problems: enabling outside access while trying to keep outsiders out.

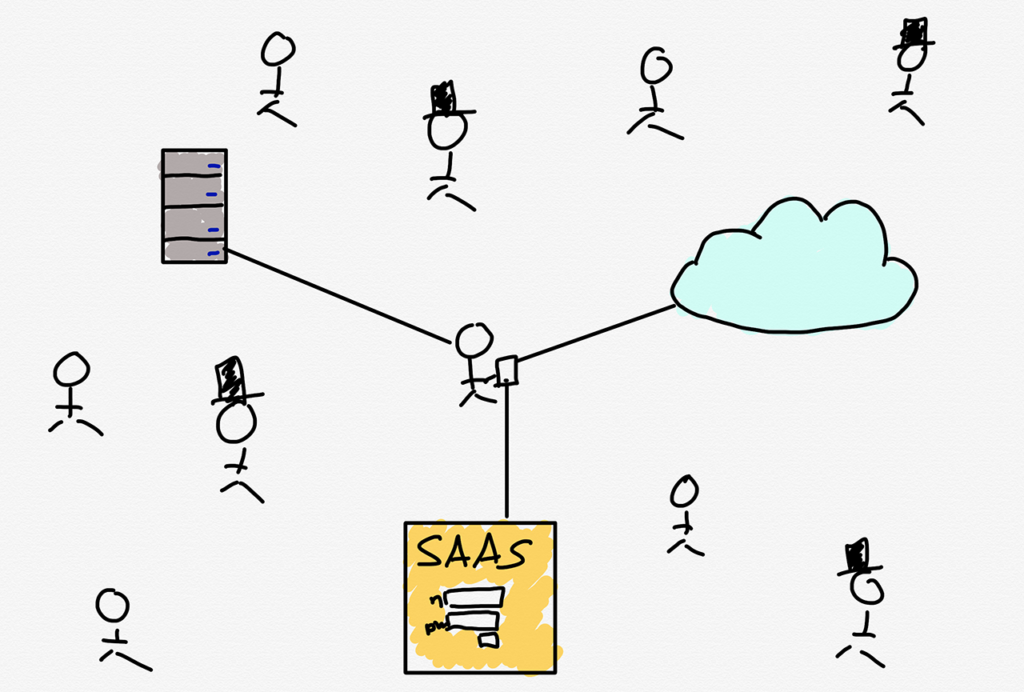

These problems were dramatically exacerbated by the three great trends of the last decade: smartphones, software-as-a-service, and cloud computing. Now instead of the occasional salesperson or traveling executive who needed to connect their laptop to the corporate network, every single employee had a portable device that was connected to the Internet all of the time; now, instead of accessing applications hosted on an internal network, employees wanted to access applications operated by a SaaS provider; now, instead of corporate resources being on-premises, they were in public clouds run by AWS or Microsoft. What kind of moat could possibly contain all of these use cases?

The answer is to not even try: instead of trying to put everything inside of a castle, put everything in the castle outside the moat, and assume that everyone is a threat. Thus the name: zero-trust networking.

In this model trust is at the level of the verified individual: access (usually) depends on multi-factor authentication (such as a password and a trusted device, or temporary code), and even once authenticated an individual only has access to granularly-defined resources or applications. This model solves all of the issues inherent to a castle-and-moat approach:

- If there is no internal network, there is no longer the concept of an outside intruder, or remote worker

- Individual-based authentication scales on the user side across devices and on the application side across on-premises resources, SaaS applications, or the public cloud (particularly when implemented with single-sign on services like Okta or Azure Active Directory).

In short, zero trust computing starts with Internet assumptions: everyone and everything is connected, both good and bad, and leverages the power of zero transaction costs to make continuous access decisions at a far more distributed and granular level than would ever be possible when it comes to physical security, rendering the fundamental contradiction at the core of castle-and-moat security moot.

Castles and Moats

Castle-and-moat security is hardly limited to corporate information; it is the way societies have thought about information generally from, well, the times of actual castles-and-moats. I wrote last fall in The Internet and the Third Estate :

In the Middle Ages the principal organizing entity for Europe was the Catholic Church. Relatedly, the Catholic Church also held a de facto monopoly on the distribution of information: most books were in Latin, copied laboriously by hand by monks. There was some degree of ethnic affinity between various members of the nobility and the commoners on their lands, but underneath the umbrella of the Catholic Church were primarily independent city-states.

With castles and moats!

The printing press changed all of this. Suddenly Martin Luther, whose critique of the Catholic Church was strikingly similar to Jan Hus 100 years earlier, was not limited to spreading his beliefs to his local area (Prague in the case of Hus), but could rather see those beliefs spread throughout Europe; the nobility seized the opportunity to interpret the Bible in a way that suited their local interests, gradually shaking off the control of the Catholic Church.

This resulted in new gatekeepers:

Just as the Catholic Church ensured its primacy by controlling information, the modern meritocracy has done the same, not so much by controlling the press but rather by incorporating it into a broader national consensus.

Here again economics play a role: while books are still sold for a profit, over the last 150 years newspapers have become more widely read, and then television became the dominant medium. All, though, were vehicles for the “press”, which was primarily funded through advertising, which was inextricably tied up with large enterprise…More broadly, the press, big business, and politicians all operated within a broad, nationally-oriented consensus.

The Internet, though, threatens second estate gatekeepers by giving anyone the power to publish:

Just as important, though, particularly in terms of the impact on society, is the drastic reduction in fixed costs. Not only can existing publishers reach anyone, anyone can become a publisher. Moreover, they don’t even need a publication: social media gives everyone the means to broadcast to the entire world. Read again Zuckerberg’s description of the Fifth Estate :

People having the power to express themselves at scale is a new kind of force in the world — a Fifth Estate alongside the other power structures of society. People no longer have to rely on traditional gatekeepers in politics or media to make their voices heard, and that has important consequences.

It is difficult to overstate how much of an understatement that is. I just recounted how the printing press effectively overthrew the First Estate, leading to the establishment of nation-states and the creation and empowerment of a new nobility. The implication of overthrowing the Second Estate, via the empowerment of commoners, is almost too radical to imagine.

The current gatekeepers are sure it is a disaster, especially “misinformation.” Everything from Macedonian teenagers to Russian intelligence to determined partisans and politicians are held up as existential threats, and it’s not hard to see why: the current media model is predicated on being the primary source of information, and if there is false information, surely the public is in danger of being misinformed?

The Implication of More Information

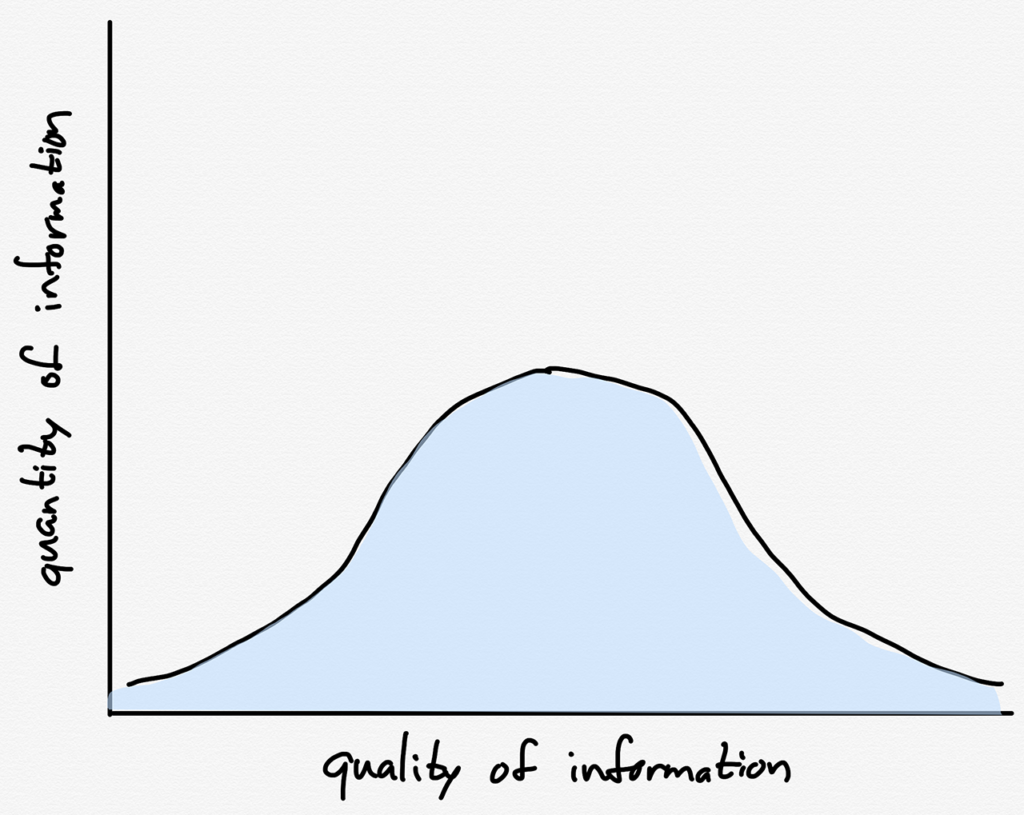

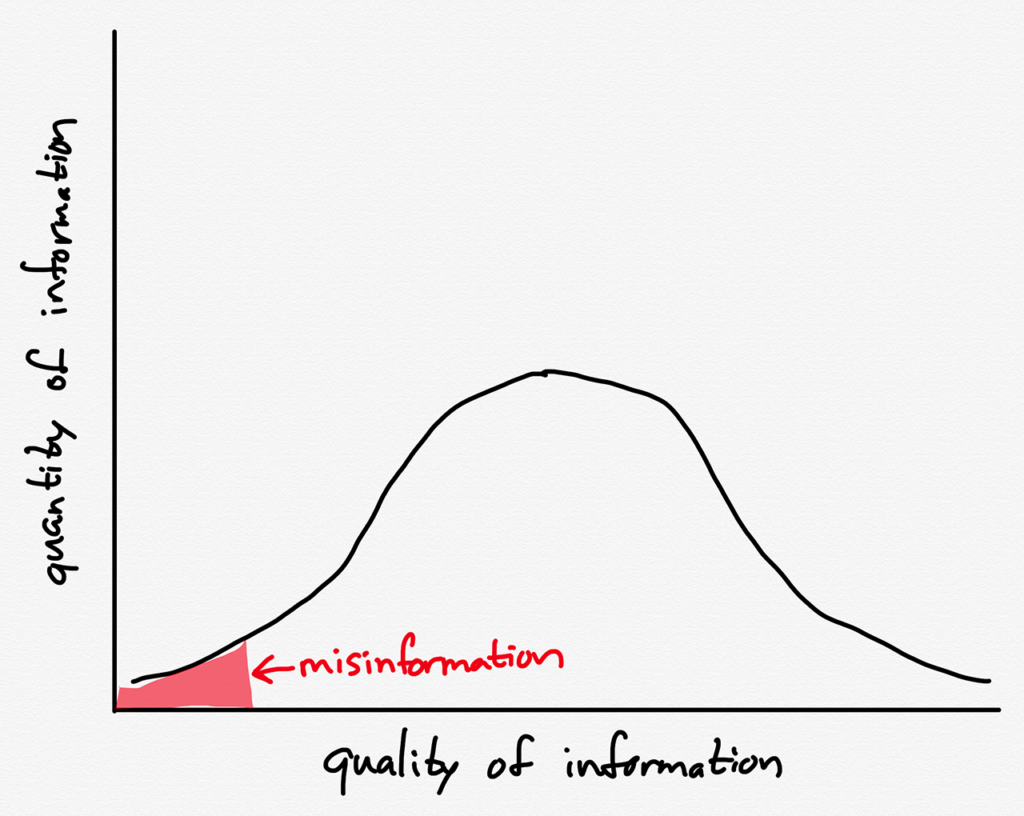

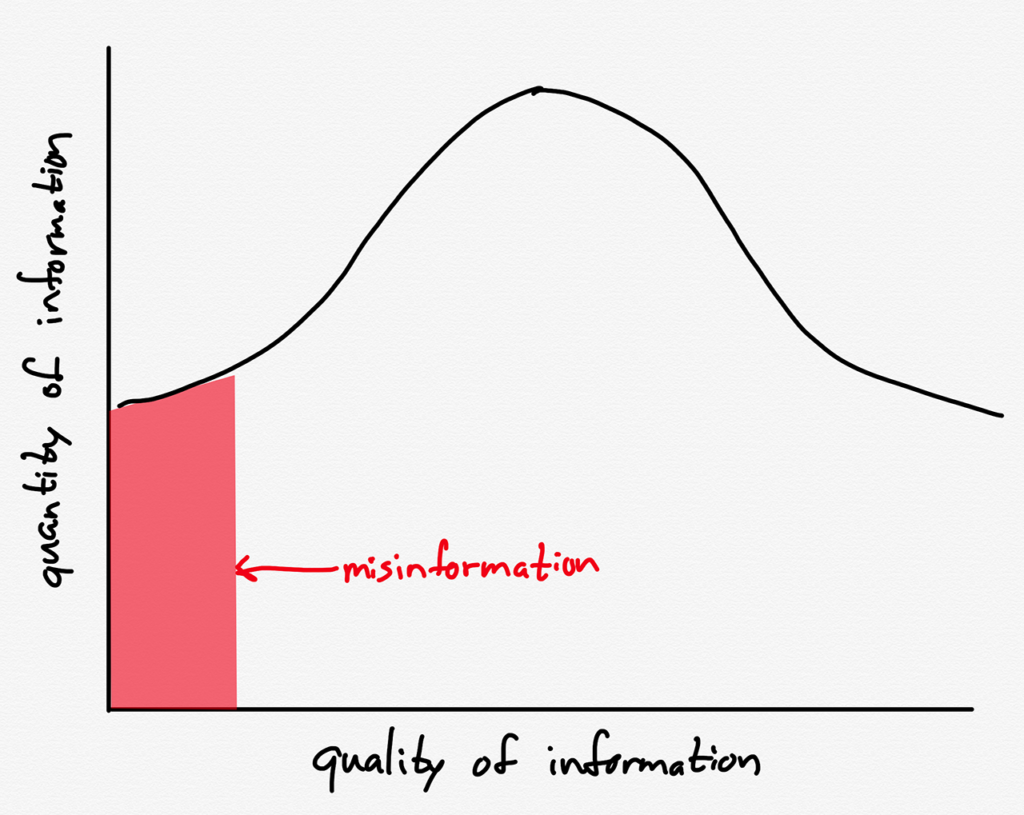

The problem, of course, is that focusing on misinformation — which to be clear, absolutely exists — is to overlook the other part of the “everyone is a publisher” equation: there has been an explosion in the amount of information available, true or not. Suppose that all published information followed a normal distribution (I am using a normal distribution for illustrative purposes only, not claiming it is accurate; obviously in sheer volume, given the ease with which it is generated, there is more misinformation):

Before the Internet, the total amount of misinformation would be low in relative and absolute terms, because the total amount of information would be low:

After the Internet, though, the total amount of information is so much greater that even if the total amount of misinformation remains just as low relatively speaking, the absolute amount will be correspondingly greater:

It follows, then, that it is easier than ever to find bad information if you look hard enough, and helpfully, search engines are very efficient in doing just that. This makes it easy to write stories like this New York Times article on Sunday:

As the coronavirus has spread across the world, so too has misinformation about it, despite an aggressive effort by social media companies to prevent its dissemination. Facebook, Google and Twitter said they were removing misinformation about the coronavirus as fast as they could find it, and were working with the World Health Organization and other government organizations to ensure that people got accurate information.

But a search by The New York Times found dozens of videos, photographs and written posts on each of the social media platforms that appeared to have slipped through the cracks. The posts were not limited to English. Many were originally in languages ranging from Hindi and Urdu to Hebrew and Farsi, reflecting the trajectory of the virus as it has traveled around the world…The spread of false and malicious content about the coronavirus has been a stark reminder of the uphill battle fought by researchers and internet companies. Even when the companies are determined to protect the truth, they are often outgunned and outwitted by the internet’s liars and thieves. There is so much inaccurate information about the virus, the W.H.O. has said it was confronting a “infodemic.”

As I noted in the Daily Update on Monday :

The phrase “a search by The New York Times” is the tell here: the power of search in a world defined by the abundance of information is that you can find whatever it is you wish to; perhaps unsurprisingly, the New York Times wished to find misinformation on the major tech platforms, and even less surprisingly, it succeeded.

A far more interesting story, to my mind, is about the other side of that distribution. Sure, the implication of the Internet making everyone a publisher is that there is far more misinformation on an absolute basis, but that also suggests there is far more valuable information that was not previously available:

It is hard to think of a better example than the last two months and the spread of COVID-19. From January on there has been extensive information about SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 shared on Twitter in particular, including supporting blog posts, and links to medical papers published at astounding speed, often in defiance of traditional media . In addition multiple experts including epidemiologists and public health officials have been offering up their opinions directly.

Moreover, particularly in the last several weeks, that burgeoning network has been sounding the alarm about the crisis hitting the U.S. Indeed, it is only because of Twitter that we knew that the crisis had long since started (to return to the distribution illustration, in terms of impact the skew goes in the opposite direction of the volume).

The Seattle Flu Study Story

Perhaps the single most important piece of information about the COVID-19 crisis in the United States was this March 1 tweet thread from Trevor Bedford , a member of the Seattle Flu Study team:

The team at the @seattleflustudy have sequenced the genome the #COVID19 community case reported yesterday from Snohomish County, WA, and have posted the sequence publicly to https://t.co/tbVb4MAGpy . There are some enormous implications here. 1/9

— Trevor Bedford (@trvrb) March 1, 2020

This case, WA2, is on a branch in the evolutionary tree that descends directly from WA1, the first reported case in the USA sampled Jan 19, also from Snohomish County, viewable here: https://t.co/gxyo0PsJ7x 2/9 pic.twitter.com/LBH26A0AFC

— Trevor Bedford (@trvrb) March 1, 2020

This strongly suggests that there has been cryptic transmission in Washington State for the past 6 weeks. 3/9

— Trevor Bedford (@trvrb) March 1, 2020

I believe we're facing an already substantial outbreak in Washington State that was not detected until now due to narrow case definition requiring direct travel to China. 6/9

— Trevor Bedford (@trvrb) March 1, 2020

You can draw a direct line from this tweet thread to widespread social distancing, particularly on the West Coast: many companies are working from home, traveling has plummeted, conferences are being canceled. Yes, there should absolutely be more, but every little bit helps ; information that came not from authority figures or gatekeepers but rather Twitter is absolutely going to save lives.

What is remarkable about these decisions, though, is that they were made in an absence of official data. The President has spent weeks downplaying the impending crisis, and the CDC and FDA have put handcuffs on state and private labs even as they have completely dropped the ball on test kits that would show what is surely a significant and rapidly growing number of cases. Incredibly, as this New York Times story documents , those handcuffs were quite explicitly applied to Bedford’s team:

[In late January] the Washington State Department of Health began discussions with the Seattle Flu Study already going on in the state. But there was a hitch: The flu project primarily used research laboratories, not clinical ones, and its coronavirus test was not approved by the Food and Drug Administration. And so the group was not certified to provide test results to anyone outside of their own investigators…

C.D.C. officials repeatedly said it would not be possible [to test for coronavirus]. “If you want to use your test as a screening tool, you would have to check with F.D.A.,” Gayle Langley, an officer at the C.D.C.’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Disease, wrote back in an email on Feb. 16. But the F.D.A. could not offer the approval because the lab was not certified as a clinical laboratory under regulations established by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, a process that could take months.

The Seattle Flu Study, led by Dr. Helen Y. Chu, finally decided to ignore the CDC:

On the other side of the country in Seattle, Dr. Chu and her flu study colleagues, unwilling to wait any longer, decided to begin running samples. A technician in the laboratory of Dr. Lea Starita who was testing samples soon got a hit…

“What we were allowed to do was to keep it to ourselves,” Dr. Chu said. “But what we felt like we needed to do was to tell public health.” They decided the right thing to do was to inform local health officials…

Later that day, the investigators and Seattle health officials gathered with representatives of the C.D.C. and the F.D.A. to discuss what happened. The message from the federal government was blunt. “What they said on that phone call very clearly was cease and desist to Helen Chu,” Dr. Lindquist remembered. “Stop testing.”

Still, the troubling finding reshaped how officials understood the outbreak. Seattle Flu Study scientists quickly sequenced the genome of the virus, finding a genetic variation also present in the country’s first coronavirus case.

And thus came Bedford’s tweetstorm, and the response from private companies and individuals that, while weeks later than it should have been, was still far earlier than it might have been in a world of gatekeepers.

The Internet and Individual Verification

The Internet, famously, grew out of a Department of Defense project called ARPANET; that was the network Cerf, Dalal, and Sunshine developed TCP for. Contrary to popular myth, though, the goal was not to build a communications network that could survive a nuclear attack, but something more prosaic: there were a limited number of high-powered computers available to researchers, and the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) wanted to make it easier to access them.

There is a reason that the nuclear war motive has stuck, though: for one, that was the motivation for the theoretical work around packet switching that became the TCP/IP protocol. Two is the fact that the Internet is in fact so resilient: despite the best efforts of gatekeepers, information of all types flows freely. 1 Yes, that includes misinformation, but it also includes extremely valuable information as well; in the case of COVID-19 it will prove to have made a very bad problem slightly better.

This is not to say that the Internet means that everything is going to be ok, either in the world generally or the coronavirus crisis specifically. But once we get through this crisis, it will be worth keeping in mind the story of Twitter and the heroic Seattle Flu Study team: what stopped them from doing critical research was too much centralization of authority and bureaucratic decision-making; what ultimately made their research materially accelerate the response of individuals and companies all over the country was first their bravery and sense of duty, and secondly the fact that on the Internet anyone can publish anything.

To that end, instead of trying to fight the Internet — to try and build a castle and moat around information, with all of the impossible tradeoffs that result — how much more value might there be in embracing the deluge? All available evidence is that young people in particular are figuring out the importance of individual verification; for example, this study from the Reuters Institute at Oxford :

We didn’t find, in our interviews, quite the crisis of trust in the media that we often hear about among young people. There is a general disbelief at some of the politicised opinion thrown around, but there is also a lot of appreciation of the quality of some of the individuals’ favoured brands. Fake news itself is seen as more of a nuisance than a democratic meltdown, especially given that the perceived scale of the problem is relatively small compared with the public attention it seems to receive. Users therefore feel capable of taking these issues into their own hands.

A previous study by Reuters Institute also found that social media exposed more viewpoints relative to offline news consumption, and another study suggested that political polarization was greatest amongst older people who used the Internet the least.

Again, this is not to say that everything is fine, either in terms of the coronavirus in the short term or social media and unmediated information in the medium term. There is, though, reason for optimism, and a belief that things will get better, the more quickly we embrace the idea that fewer gatekeepers and more information means innovation and good ideas in proportion to the flood of misinformation which people who grew up with the Internet are already learning to ignore.

- China is an obvious exception; I addressed the contrast in the aforelinked “The Internet and the Third Estate”. [ ↩ ]

文章版权归原作者所有。