Defining Information

Defining Information

Last Wednesday morning, I wrote a piece called Zero Trust Information , where I lauded social media generally and Twitter specifically for functioning as an early warning system for the impending coronavirus crisis. For weeks a motley collection of folks — some epidemiologists and public health officials, but many not — had been sounding the alarm on Twitter about the exponential spread of SARS-CoV-2 and the impact the resultant COVID-19 disease would have on health care systems, culminating in a member of the Seattle Flu Study tweeting the results of an illegal test showing community transmission in Washington State. As I wrote in that piece:

Once we get through this crisis, it will be worth keeping in mind the story of Twitter and the heroic Seattle Flu Study team: what stopped them from doing critical research was too much centralization of authority and bureaucratic decision-making; what ultimately made their research materially accelerate the response of individuals and companies all over the country was first their bravery and sense of duty, and secondly the fact that on the Internet anyone can publish anything.

Later that night, after a presidential address, the infection of Tom Hanks, and the suspension of the NBA, the rest of the country finally woke up, and along the way, something interesting happened: Twitter became a much worse source of information.

Information Over Time

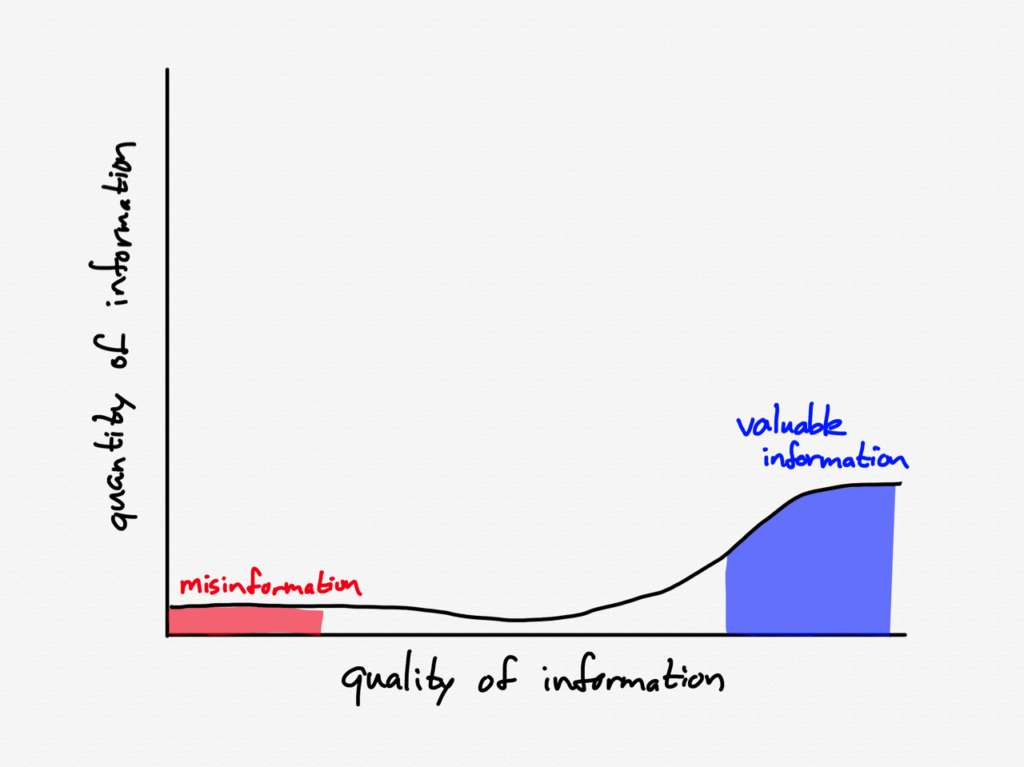

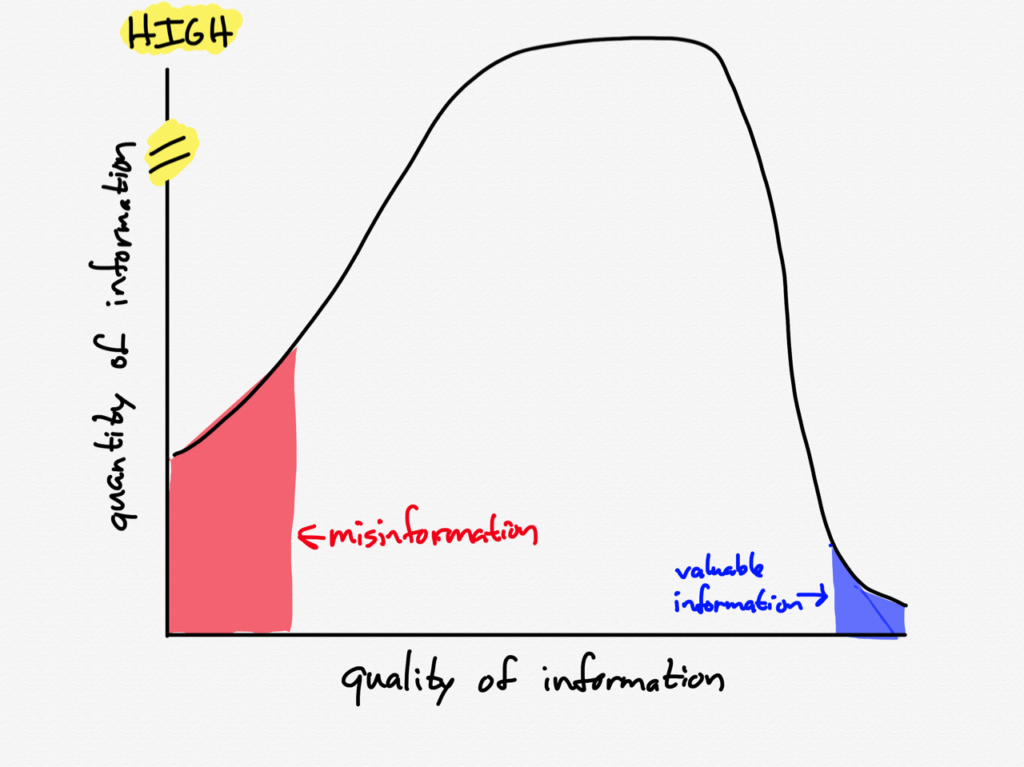

The biggest complaint I received about Zero Trust Information was this graph, which some folks argued misrepresented the situation online:

While I used a normal distribution for illustrative purposes, not as an assertion about relative volumes, I can understand why some people took it literally; in fact, my only point was to show that an increase on the negative left side of the distribution — whatever that distribution ultimately looks like — was enabled by the exact same forces that allowed for an increase on the positive right side of the distribution.

I would make two further observations: first, generally speaking, the left side of that distribution — again, whatever it looks like — is almost certainly larger in quantity than the right side; producing misinformation is cheap and can even be automated (i.e. misinformation bots on social media). At the same time, when you consider something like the coronavirus, the right side of the distribution is massively larger in impact.

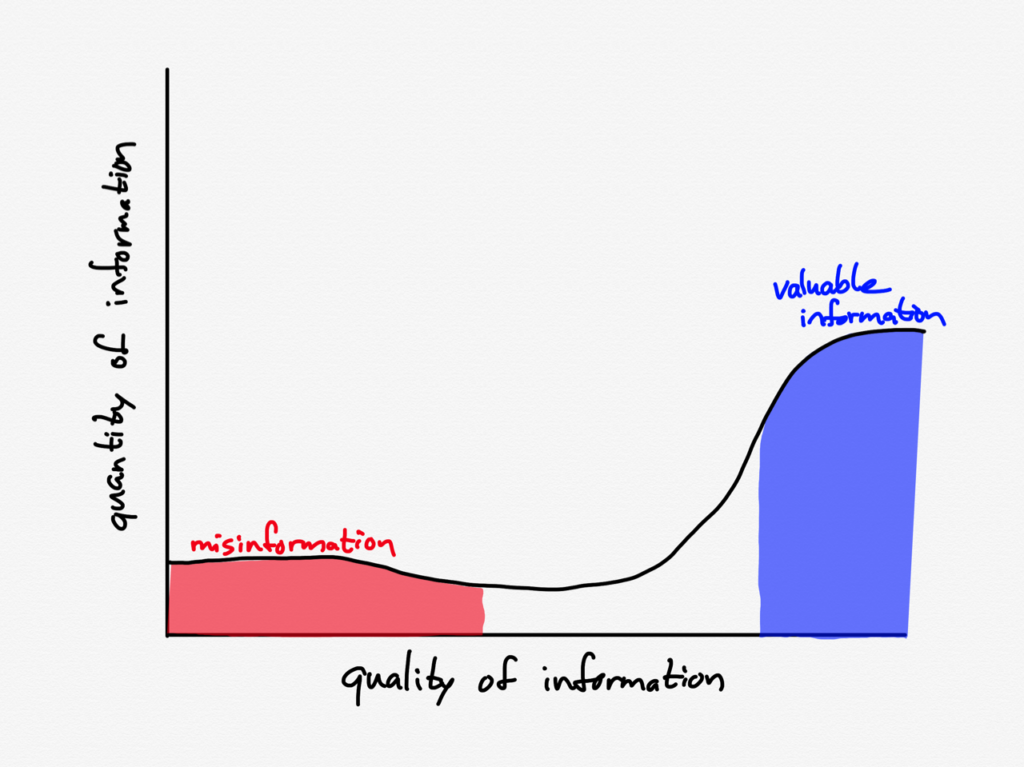

What I noticed over the last week, though, is how these things change over time. Consider some variations of the above graph — none of which, I must stress, are making specific assertions about quantities, but which I suspect are directionally correct.

Here is what the coronavirus information graph might have looked like in early February:

There was a lot of valuable chatter on Twitter discussing the potential impact of the coronavirus, a bit of China-focused coverage in the media (which was largely focused on President Trump’s impeachment trial), and relatively little misinformation. Note also that the absolute amount of information was quite small.

By late February it looked like this:

There was a huge amount of chatter on Twitter discussing the potential impact of the coronavirus, as well as an increasing number of people — and media — arguing it was “just the flu” (that is the part under misinformation); overall coverage was higher but still relatively muted.

The first week of March looked like this:

Note how the total amount of information was rising significantly, particularly valuable information on Twitter as well as increased media coverage.

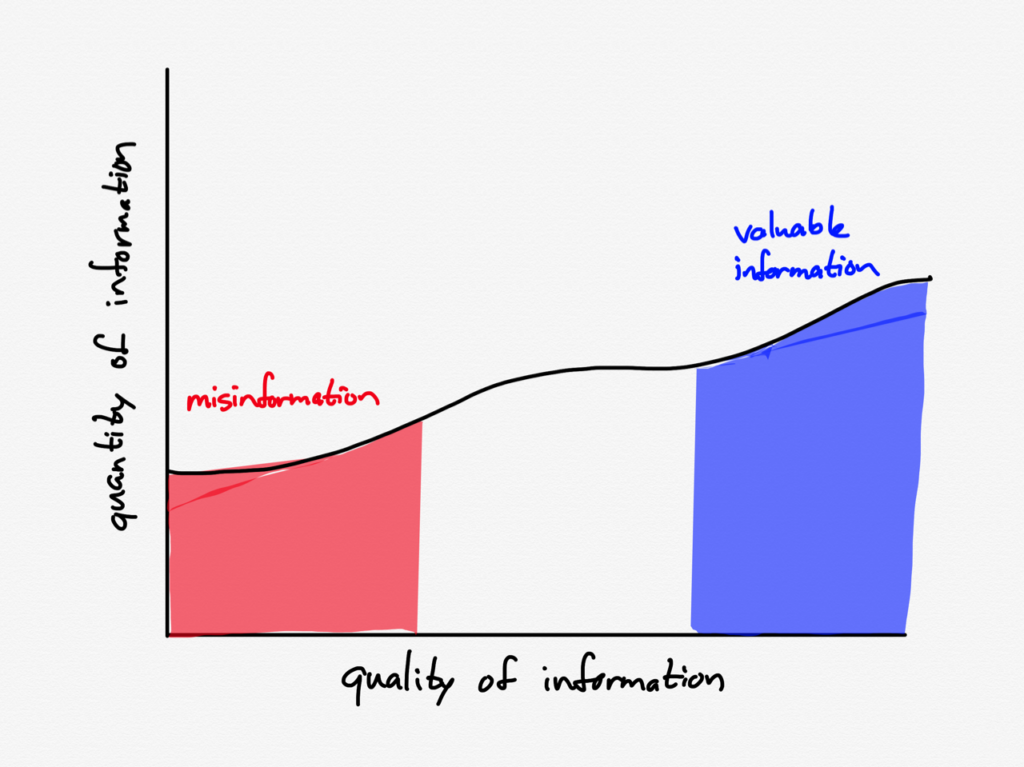

Then came the events of last Wednesday, and the information graph exploded:

Pretty much by definition the most growth in information happened on the left two-thirds of the graph. There were very few people who learned about the coronavirus last week who were offering meaningfully interesting new information on Twitter; there were plenty, though, that were passing along whatever information they could get their hands on without much care as to whether it was accurate or not.

(Computer) Viruses

If you will permit a digression about a very different type of virus, back in the 2000s one of the eternal debates on message boards and comment threads was the relative security of Windows versus the Mac. Apple would advertise that Macs had far fewer viruses (brace yourself for a startling lack of social distancing):

Back in 2006, when this commercial was released, there were several aspects of Unix-based Macs that were more secure than pre-Vista Windows, including a better security model and privilege escalation checks, enforced filesystem permissions, better browser sandboxing, etc. Just as important, though, was the fact there just weren’t that many Macs, relatively speaking.

A virus is, after all, a program, which means that someone needs to write it, debug it, and distribute it. Given that over 90% of the PCs in the world ran Windows, writing a virus for Windows offered a far higher return on investment for hackers that were primarily looking to make money.

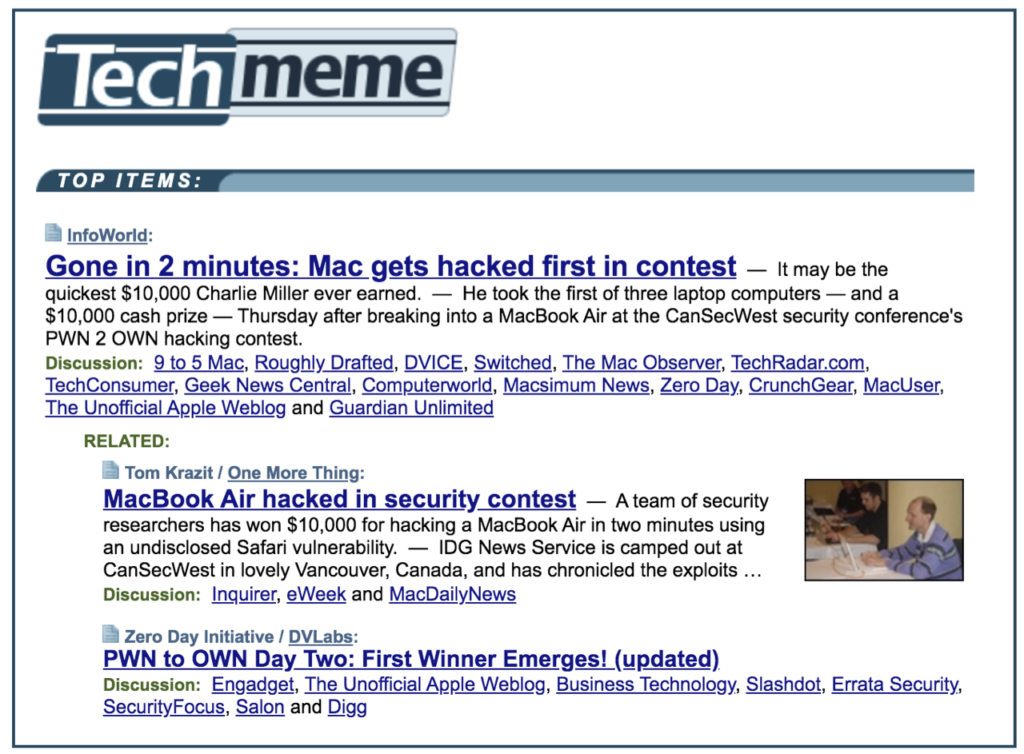

Notably, though, if your motivation was something other than money — status, say — you attacked the Mac. That is what earned headlines :

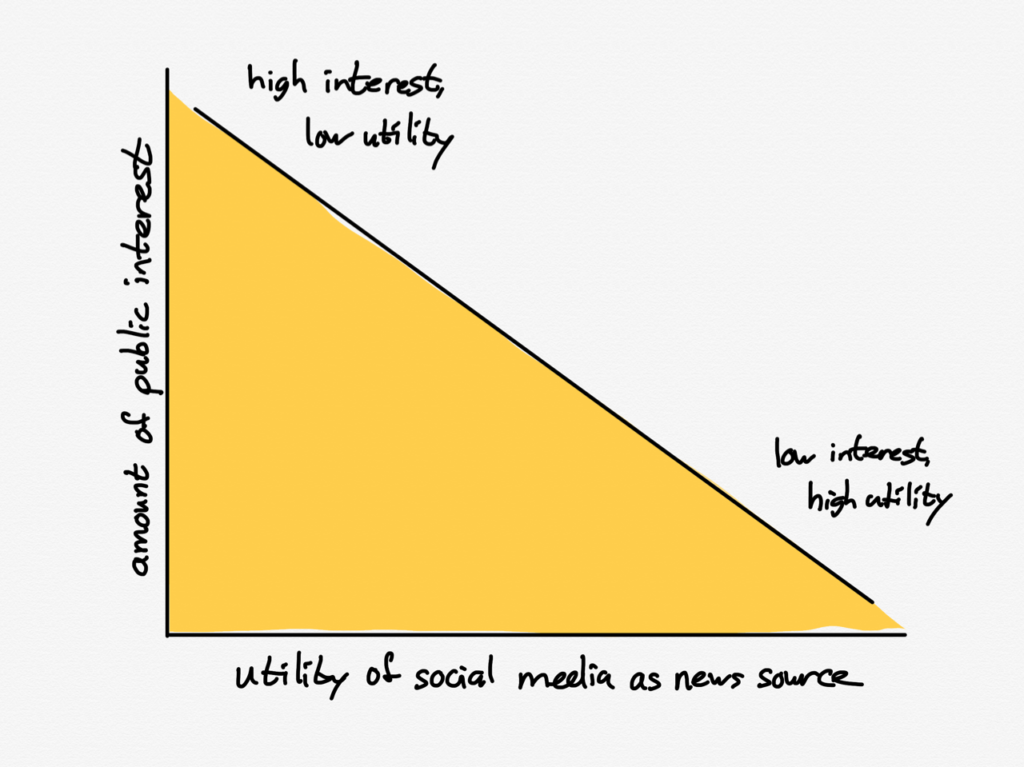

I suspect we see the same sort of dynamic with information on social media in particular; there is very little motivation to create misinformation about topics that very few people are talking about, while there is a lot of motivation — money, mischief, partisan advantage, panic — to create misinformation about very popular topics.

In other words, the utility of social media as a news source is inversely correlated to how many people are interested in a given topic:

This makes intuitive sense: social networks are often about friends and family, which are intensely important to you but not to anyone else, because they care about their own friends and family. Needless to say, Macedonian teens aren’t spreading rumors about Aunt Virgina or Uncle Robert.

They also weren’t talking about the coronavirus — but people who cared were.

Information Types

The title Zero Trust Information was an analogy to Zero Trust Networking , which authenticates at the level of the individual, instead of relying on the castle-and-moat model which cared whether or not a device is behind a firewall. Generally an individual has to have both a valid password and a verified device to access sensitive information and applications from anywhere on the Interent — including on the corporate network. My argument is that information verification also has to happen at the level of the individual, but what is the equivalent of a password and verified device?

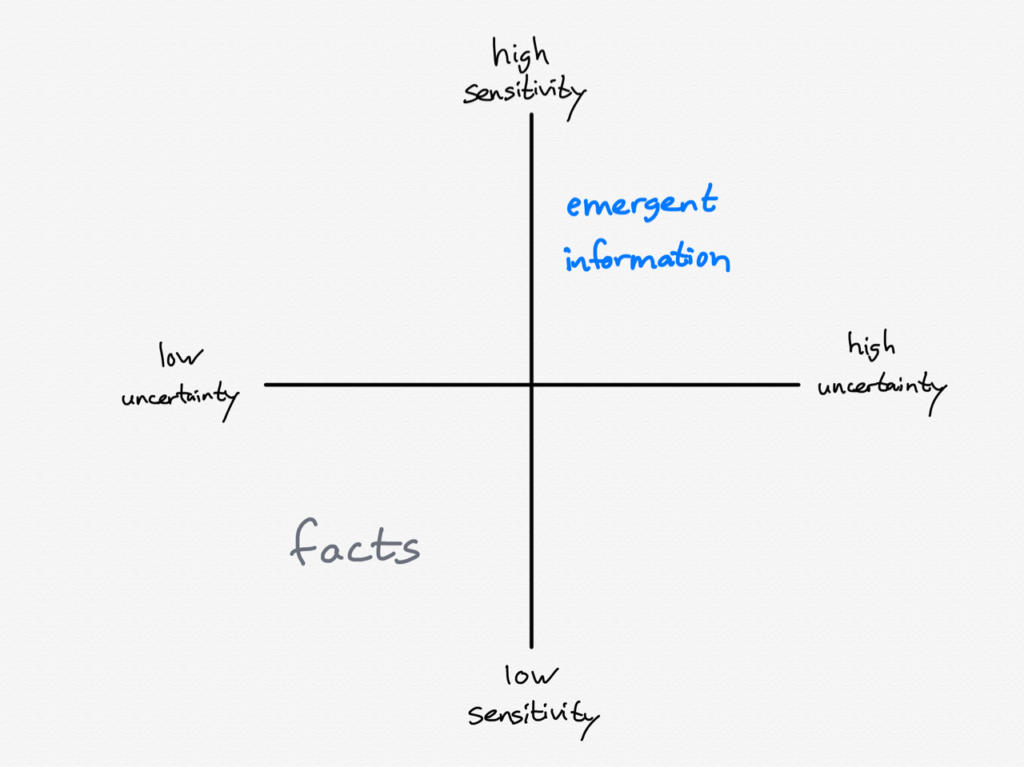

I think an understanding of the the different types of information and how it is distributed gives some helpful heuristics:

- For emergent information, like the coronavirus in February, you need a high degree of sensitivity and a high tolerance for uncertainty.

- For facts, like the coronavirus right now, you need a much lower degree of sensitivity and a much lower tolerance of uncertainty: either something is verifiably known or it isn’t.

You could even make a two-by-two:

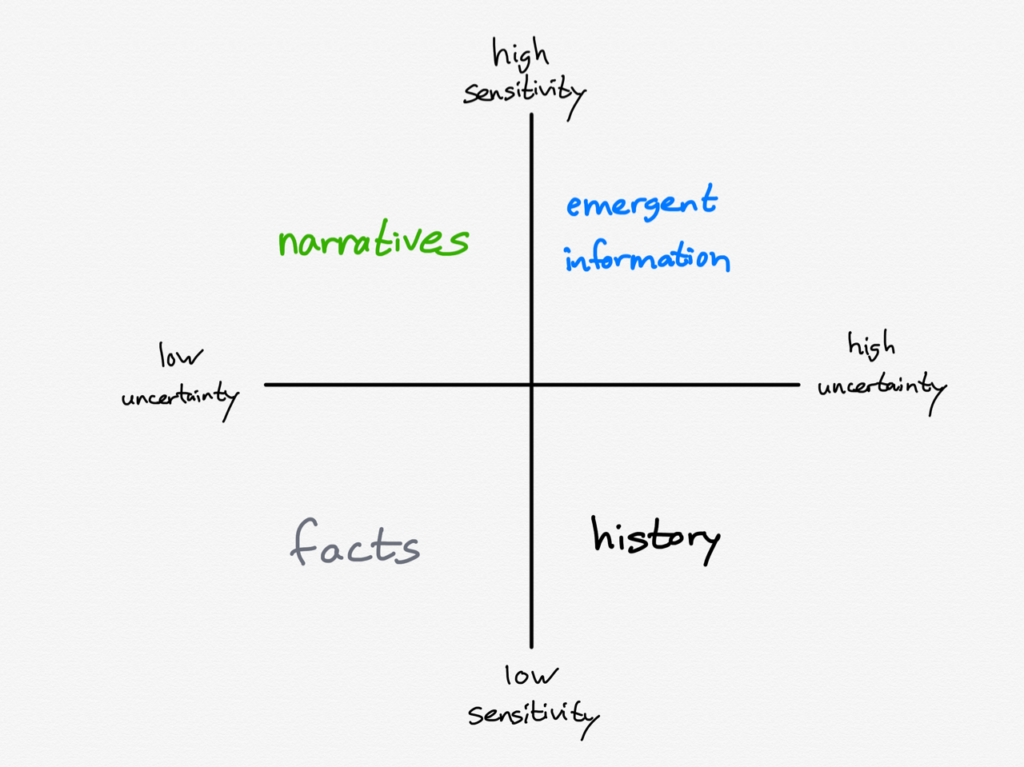

It is interesting, by the way, to consider what fits in the other two corners:

Narratives around ongoing stories rely on a high degree of sensitivity (in an attempt to find the narrative thread) and a low tolerance for uncertainty (in an attempt to sell the narrative). History, on the other hand, requires a low degree of sensitivity (record what matters) and a high tolerance of uncertainty (we weren’t there).

Information Business Models

There is also a business model aspect to these different types of information. To return to The Internet and the Third Estate :

The economics of printing books was fundamentally different from the economics of copying by hand. The latter was purely an operational expense: output was strictly determined by the input of labor. The former, though, was mostly a capital expense: first, to construct the printing press, and second, to set the type for a book. The best way to pay for these significant up-front expenses was to produce as many copies of a particular book that could be sold.

How, then, to maximize the number of copies that could be sold? The answer was to print using the most widely used dialect of a particular language, which in turn incentivized people to adopt that dialect, standardizing language across Europe. That, by extension, deepened the affinities between city-states with shared languages, particularly over decades as a shared culture developed around books and later newspapers.

This model was ideal for information that required a low degree of sensitivity — facts and history. It required a fair bit of expense upfront to create a newspaper or a book, and the way to gain maximum leverage on that expense was to produce things that were valuable to the most people possible.

The Internet, though, changed the cost equation on the production side too:

What makes the Internet different from the printing press? Usually when I have written about this topic I have focused on marginal costs: books and newspapers may have been a lot cheaper to produce than handwritten manuscripts, but they are still not-zero. What is published on the Internet, meanwhile, can reach anyone anywhere, drastically increasing supply and placing a premium on discovery; this shifted economic power from publications to Aggregators.

Just as important, though, particularly in terms of the impact on society, is the drastic reduction in fixed costs. Not only can existing publishers reach anyone, anyone can become a publisher. Moreover, they don’t even need a publication: social media gives everyone the means to broadcast to the entire world.

This is what made both emergent information and narratives not just financially viable, but in fact more lucrative than facts or history. Emergent information can come from anywhere, which is another way of saying anyone can publish, and most of what people have to say is really only interesting to a small circle of friends and family. That, though, scales perfectly with the Internet’s free distribution, capturing the attention of everyone individually, which can then be sold to advertisers.

As for narratives, at their best they appeal to the innate human desire for stories and our desire to make sense of the world; at their worst they appeal to people’s confirmation bias and tribal instincts. Either way, they tend to be polarizing, which is bad news in a world of fixed up-front costs, but exactly what you want when production is cheap and attention is scarce.

Again, neither emergent information nor narratives are inherently bad. Both, though, can lead to bad outcomes: emergent information can be easily overwhelmed by misinformation, particularly when the incentives are wrong, and narratives can themselves corrupt facts. Or, as I narrated last week, they can reveal valuable information that would not otherwise be published.

The Clarifying Coronavirus

In some respects this discussion feels besides the point; there are lot of people suffering right now, and everyone is scared. Some will get COVID-19, some will die, and everyone will have their lives disrupted.

Perhaps, though, that is why the coronavirus seems so clarifying when it comes to defining information. Emergent information was critical, both in terms of being censored in China , and in how it helped sound the alarm in the U.S. That success, though, was met by the failure of allowing narratives to obscure facts, whether those narratives were “just the flu”, or a suggestion of a media conspiracy, or mocking excitable tech bros on Twitter. And, looming over it all, is the reality that this moment will make it into the history books.

文章版权归原作者所有。