Dithering and Open Versus Free

Dithering and Open Versus Free

The big news, in case you haven’t yet heard: John Gruber and I have launched a new podcast called Dithering :

Dithering costs $5/month or $50/year. If you’re a Stratechery subscriber, it costs $3/month or $30/year to add it as a bundle . 1

Dithering covers some of the same topics as Stratechery — the Dithering web page has a descriptive lists of topics — but in the conversational style that many of you have enjoyed on my appearances on Gruber’s The Talk Show podcast , or in the Daily Update Interview I did with Gruber last Thursday . 2 Expect less in-depth analysis than a typical Stratechery post, and more back-and-forth, with the occassional foray into non-tech topics. All in fifteen minutes, exactly. It’s perfect for your dishwashing commute!

That time limit is certainly a challenge (that is why we recorded 20 episodes before we launched — the entire back catalog is available to subscribers), but we really wanted to experiment with what a podcast might be. We purposely don’t have show notes or much of a web page, and we have created evocative cover art embedded in each episode’s MP3, because the canonical version of Dithering is in your podcast player. This is as pure a podcast as can be — and that means open, even if it isn’t free.

Open != Free

I’m used to dealing with the seeming contradiction between open and free : back in 2014 I started selling an email I called the Daily Update . There was no special app required, and while Daily Updates were archived on the web, I took care to not shove a paywall in your face; if you wanted more content from me you could pay for more, and I would send you an email over the open SMTP protocol, that landed in the email client you already used.

This combination of open and for-pay turned out to be extraordinarily powerful: even as closed but free feeds like Facebook were turning into pay-to-play for publishers, email remained the only feed that everyone checked every day that didn’t have a gatekeeper, which made it the best possible means of delivering the value proposition I was charging for — a proposition I most clearly defined in 2017’s The Local News Business Model :

It is very important to clearly define what a subscriptions means. First, it’s not a donation: it is asking a customer to pay money for a product. What, then, is the product? It is not, in fact, any one article (a point that is missed by the misguided focus on micro-transactions). Rather, a subscriber is paying for the regular delivery of well-defined value.

The importance of this distinction stems directly from the economics involved: the marginal cost of any one Stratechery article is $0. After all, it is simply text on a screen, a few bits flipped in a costless arrangement. It makes about as much sense to sell those bit-flipping configurations as it does to sell, say, an MP3, costlessly copied.

So you need to sell something different.

In the case of MP3s, what the music industry finally learned — after years of kicking and screaming about how terribly unfair it was that people “stole” their music, which didn’t actually make sense because digital goods are non-rivalrous — is that they should sell convenience. If streaming music is free on a marginal cost basis, why not deliver all of the music to all of the customers for a monthly fee?

This is the same idea behind nearly every large consumer-facing web service: Netflix, YouTube, Facebook, Google, etc. are all predicated on the idea that content is free to deliver, and consumers should have access to as much as possible. Of course how they monetize that convenience differs: Netflix has subscriptions, while Google, YouTube, and Facebook deliver ads (the latter two also leverage the fact that content is free to create). None of them, though, sells discrete digital goods. It just doesn’t make sense.

Aggregators Versus Publishers

This model is pretty good for consumers: they get access to an abundance of content for a set price. It’s great for the Aggregators: because they have so many consumers, the suppliers of content are forced to accede to the Aggregator’s terms, even as Aggregators are best placed to serve advertisers. That is another way of saying that it is the individual content maker that is getting the short end of the stick:

- On Spotify, individual artists make fractions of a cent per play, and their payout is based on their share of all Spotify plays; if you have a super-fan that listens to nothing but your songs, you still only get a few pennies.

- On Netflix, show creators are getting bigger payments up front, but in return they are giving up residuals and international rights; Netflix owns all of the upside.

- YouTube is actually one of the more creator-friendly Aggregators: what you earn is pretty closely tied to how many views you achieve. That, though, means a hamster wheel lifestyle of constantly churning out content and begging for subscribers, even as it requires ever more views to achieve the same amount of money. And, of course, YouTube could de-monetize you at any time, for any reason.

- Google helps consumers find content, but because (all of the) consumers start with search, so do advertisers; Facebook lets consumers make content, and then favors it over professionally produced links.

It is important to note that, the constant griping of traditional gatekeepers notwithstanding, Aggregators are by definition good for most content creators; after all, everyone is now a content creator, whereas previously publishing was reserved for those who had access to physical assets like printing presses, recording studios, or broadcast towers. That means most people are publishing for the first time (with effects both good and bad ).

It also means that traditional publishers face more competition for attention, and, as long as they rely on Aggregators, an inherently unstable source of income: one big song, show, video, or article can make some money, but without an ongoing connection and commitment from the consumer to the content creator, it is increasingly impossible to make a living.

Subscriptions and Open Protocols

This is why subscriptions — “paying for the regular delivery of well-defined value” — are so important. I defined every part of that phrase:

- Paying: A subscription is an ongoing commitment to the production of content, not a one-off payment for one piece of content that catches the eye.

- Regular Delivery: A subscriber does not need to depend on the random discovery of content; said content can be delivered to the subscriber directly, whether that be email, a bookmark, or an app.

- Well-defined Value: A subscriber needs to know what they are paying for, and it needs to be worth it.

This runs in the opposite direction of a Spotify-type model, even as it takes advantage of the same foundation of zero marginal costs. If an email is an artifact of hard work creating something people are interested in, the open ecosystem of HTTP and SMTP drives the costs of delivering that artifact to zero. There is no massive streaming infrastructure to build, nor endless data centers in the cloud — this can all be rented for not much money at all — which means that the cost structure of an independent creator can be dramatically lower than any traditional publisher, even as their addressable market is the same size .

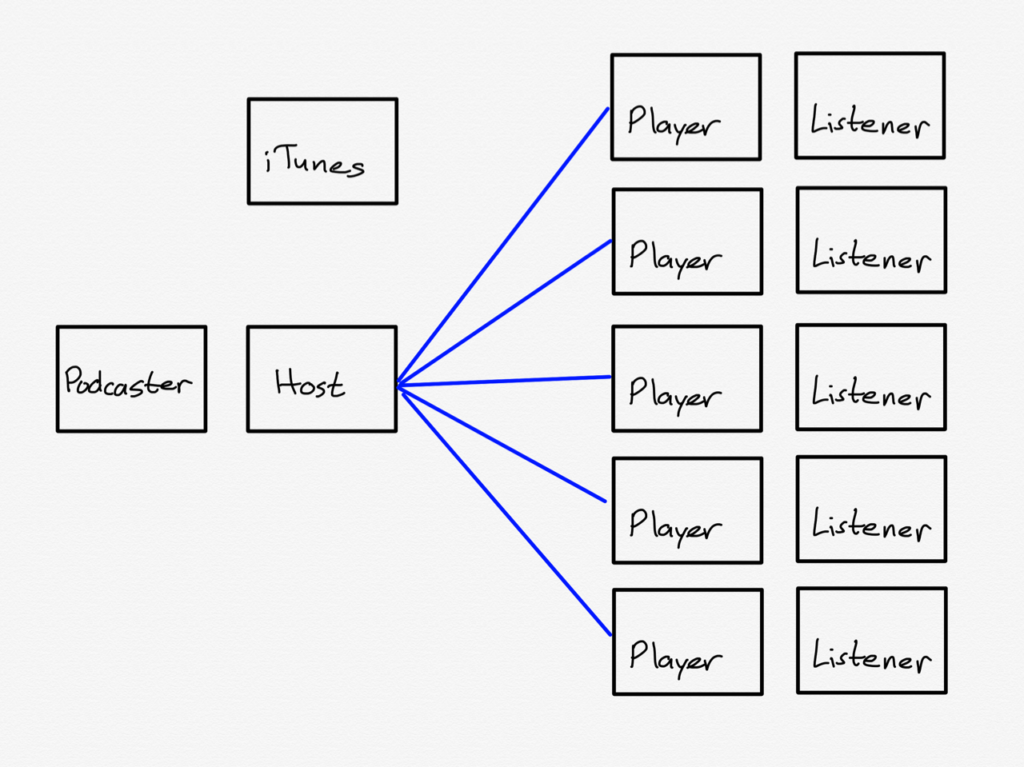

HTTP and SMTP, though, are not the only open protocols available to publishers: RSS is another, and it is the foundation of the podcast ecosystem. Most don’t understand that podcasts are not hosted by Apple, but rather that iTunes is a directory of RSS feeds hosted on servers all over the Internet. When you add a podcast to your podcast player, you are simply adding an RSS feed that includes information about the show, and a link for where to download new episodes.

This, if you squint, looks a lot like email: create something that listeners find valuable on an ongoing basis, and deliver it into a feed they already check, i.e. their existing podcast player. That is Dithering : while you have to pay to get a feed customized to you , that feed can be put in your favorite podcast app, which means Dithering fits in with the existing open ecosystem, instead of trying to supplant it.

Well, almost all podcast apps: Spotify is an exception. 3

Spotify’s Facebook Play

Podcasting, as I wrote last year , looks a lot like the early web; iTunes is the Yahoo directory, and advertising is punching the monkey:

The current state of podcast advertising is a situation not so different from the early web: how many people remember this?

These ads were elaborate affiliate marketing schemes; you really could get a free iPod if you signed up for several credit cards, a Netflix account, subscription video courses, you get the idea. What all of these marketers had in common was an anticipation that new customers would have large lifetime values, justifying large payouts to whatever dodgy companies managed to sign them up.

The parallels to podcasting should be obvious: why is Squarespace on seemingly every podcast? Because customers paying monthly for a website have huge lifetime values. Sure, they may only set up the website once, but they are likely to maintain it for a very long time, particularly if they grabbed a “free” domain along the way. This makes the hassle of coordinating ad reads and sponsorship codes across a plethora of podcasts worth the trouble; it’s the same story with other prominent podcast sponsors like ZipRecruiter or SimpliSafe.

Some are content with this state of affairs, and I understand the sentiment: the early web, annoying banner ads notwithstanding, was in many respects a nicer place as well, and some folks even made money. The problem, though, is it didn’t last: once Google and Facebook figured out that the best way to advertise was to aggregate users and deliver targeted ads, the open web withered; it is only in the last few years that, thanks to email, independent publishing is making a return.

I strongly believe that podcasting is approaching a similar precipice; I wrote a year ago that Spotify wants to be the podcast Aggregator:

What I think Spotify senses, though, is that while podcasts, at least in theory, solve many of their business model problems, Spotify is also uniquely positioned to solve the problems of many podcasters/suppliers. To wit:

- Increasing advertising revenue for the entire industry requires a centralized player that can leverage a large userbase. Spotify is still a distant second to Apple in podcasts, but they are growing fast. Just as importantly, Spotify already has a strongly growing advertising business — again, larger than the entire podcast market — that it can extend to podcasts.

- The open nature of podcasts means it is very difficult to monetize users directly; Spotify, though, has already built an entire infrastructure around monetizing users directly. Podcasts exclusive to Spotify can likely make meaningful money from Spotify subscribers that still gives Spotify far higher margin than music.

Spotify CEO Daniel Ek made clear that this was the goal after the company acquired The Ringer; from the Q1 2020 earnings call :

When we look at the overall opportunity, it is pretty clear that we haven’t added Internet-level monetization yet to audio. So, all the things that you’ve come to expect in video and display in terms of measurability, in terms of just targeting, a lot of that is lacking in podcasts today. And you’ve seen it time and time again. As you add those capabilities, you generally can raise CPMs across the board, because advertisers feel more certain about the results that they’re getting. And if we do that, that’s going to be a tremendous benefit for all the podcasting creators, but it’s also going to be a tremendous benefit for Spotify.

This is why Spotify adjusted its accounting last quarter to recognize the cost of its owned-and-operated podcast production as an expense for its advertising business; the company isn’t primarily focused on acquiring paying subscribers, although that is a nice side effect of increased engagement on Spotify. The real goal is to intermediate podcasters and listeners and take over podcast advertising just like Facebook and Google took over web advertising.

That, though, is bad for openness — indeed, Spotify isn’t open at all. You can’t simply add an RSS feed to Spotify, as you can most other podcast players. Rather, podcasters have to submit their feeds to Spotify and agree to the service’s terms of service , which can be changed at any time at Spotify’s sole discretion. Sure, the terms are relatively benign today; they could include the right to insert advertising tomorrow. Even if that doesn’t happen, though, Spotify still is not open: they can take down your content or choose not to play it, just as Facebook could not show your page unless you were willing to pay-to-play.

This is where, as I noted when I launched the Daily Update podcast , it is important to distinguish between my role as analyst, podcaster, and publisher:

Analyst Ben says it is a good idea for Spotify to try and be the Facebook of podcasting…Writer/Podcaster Ben certainly sees the allure: having my podcast available to Spotify’s 271 million monthly active users would be great; for that matter, having this Daily Update read by everyone I could reach on Facebook would be great as well. I’ve already put in the work, why not reach everyone? Indeed, were I supported by advertising, that would be the imperative.

Publisher Ben, though, remembers that my business model is predicated on a higher average revenue per user (thanks to subscriptions), not a higher number of users; that means making tradeoffs, and foregoing wide reach is one of them. That, by extension, means not agreeing to Spotify’s terms for Exponent, and accepting that leveraging RSS to have per-subscriber feeds makes having the Daily Update Podcast on Spotify literally impossible. More broadly, owning my own destiny as a publisher means avoiding Aggregators and connecting directly with customers.

Dithering is another effort driven by Publishers Ben and John; if we are to maintain a thriving podcast ecosystem that is open, we must figure out monetization, and from my perspective, that means subscriptions. The fact that Spotify won’t even allow Dithering to be played on their app only increases the urgency: if the choice is free and closed versus for-pay and open I will always push for the latter — three times a week, 15 minutes per episode.

Some additional notes on Dithering and the service powering it:

- Yes, there are several companies building out paid podcasting services. None of them had all of the features I wanted, including full control over hosting, the ability to create bundles, and customized feeds based on subscription status; to paraphrase Alan Kay , I’m serious about figuring out how paid podcasts might be a sustainable business not only for me but for the entire ecosystem, and that meant building my own software to maximize experimentation.

文章版权归原作者所有。