The Slack Social Network

On November 2, 2016, Microsoft announced Teams at a special event in New York City. Slack decided to mark the occasion:

That feeling when you think "we should buy a full page in the Times and publish an open letter," and then you do.

pic.twitter.com/BQiEawRA6d

— Stewart Butterfield (@stewart) November 2, 2016

</div>

The text of the ad was condescension cloaked in congratulations:

Dear Microsoft,

Wow. Big news! Congratulations on today’s announcements. We’re genuinely excited to have some competition.

We realized a few years ago that the value of switching to Slack was so obvious and the advantages so overwhelming that every business would be using Slack, or “something just like it,” within the decade. It’s validating to see you’ve come around to the same way of thinking. And even though — being honest here — it’s a little scary, we know it will bring a better future forward faster.

However, all this is harder than it looks. So, as you set out to build “something just like it,” we want to give you some friendly advice.

Slack’s “advice” was, naturally, self-serving, at least in terms of how the startup saw their advantages relative to Microsoft; to quote the ad:

- It’s not the features that matter

- An open platform is essential

- You’ve got to do this with love

The advertisement added under that last point:

We love our work, and when we say our mission is to make people’s working lives simpler, more pleasant, and more productive, we’re not simply mouthing the words. If you want customers to switch to your product, you’re going to have to match our commitment to their success and take the same amount of delight in their happiness.

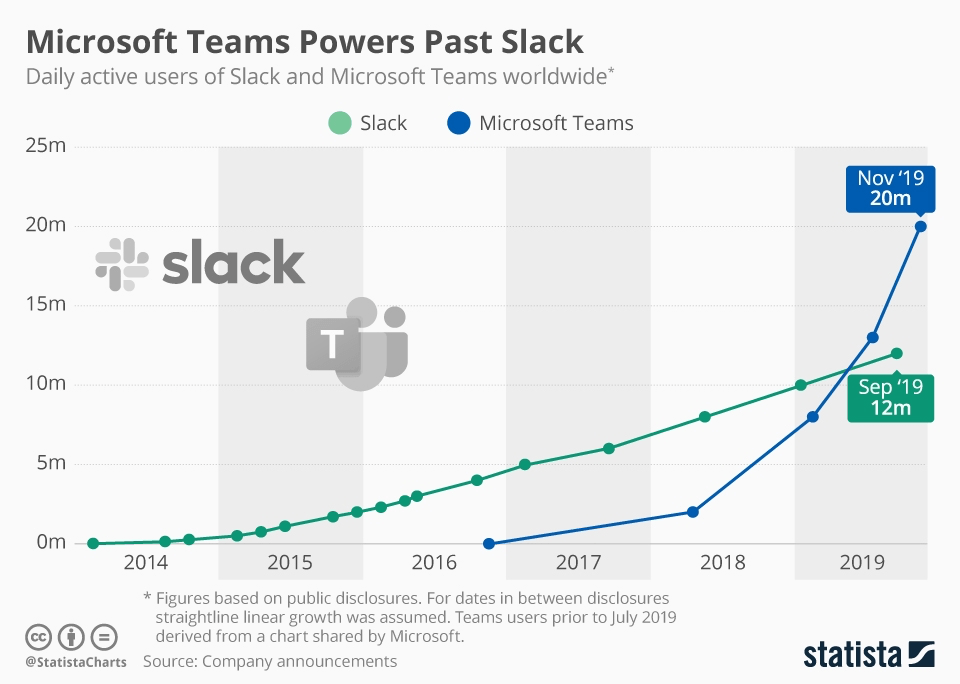

Two-and-a-half years later Teams passed Slack in daily active users (DAUs). On the company’s last earnings call CEO Satya Nadella revealed that Teams had 75 million daily active users; Slack hasn’t provided a post-pandemic-onset DAU number, but had 12 million last October (Microsoft’s pre-pandemic number was 32 million in early March). And while Slack’s ad may have welcomed Microsoft as a competitor, now CEO Stewart Butterfield is saying that Teams isn’t a competitor after all.

Fortunately for Slack, that is increasingly true.

Microsoft Strikes Back

I have long quipped that most of Silicon Valley has serially underestimated Facebook because it is the social network of friends and family, and many people in tech are trying to escape said friends and family. You can say the same thing about Microsoft: while the company was once the disruptive upstart, for decades it has been the default for all of those businesses that Silicon Valley is seeking to disrupt. Ergo, if those businesses are surely doomed, then so is Microsoft.

Moreover, just as Twitter is the social network of choice within the tech ecosystem, the vast majority of Silicon Valley companies host their email with Google and use Google’s productivity software, or one of the myriad of offerings seeking to usurp documents or spreadsheets or presentations. And even when it comes to the cloud, the choice for startups is usually between AWS and Google Cloud Platform. Microsoft is out-of-sight and out-of-mind.

And then something mysterious occurs; an enterprise SaaS company will grow like a weed, getting buzz amongst investors and the press that covers them, raise rounds for growth, perhaps even IPO, and then, well, Teams versus Slack happens:

The obvious reason for Teams’ success relative to Slack is the oldest tactic in the book: Teams is free, and Slack isn’t. Well, technically, Teams requires a n Office

Microsoft 365 subscription (although yes, there are free versions of both Teams and Slack), but as Slack itself notes, a good portion of its addressable market has exactly that. In other words, the effective choice is exactly what I stated: “free” versus paid.

Moreover, while Slack concluded its advertisement by talking about how difficult it would be for Microsoft to convince Slack users to “switch” to Teams, switching was never the goal: just as Facebook created Instagram Stories to remove the impetus for new users to even try Snapchat, Teams is particularly effective as a way to prevent a Microsoft customer from even trying Slack. And, in that case, it doesn’t matter how much “love” Slack put into its product: said love was not simply unrequited, but unexperienced.

Still, it is not as if all of those Teams users started using the program because they were inspired by Slack: Microsoft has a huge sales team with relationships that go back years, and a massive partner network that serves companies that are too small to sell to directly; I wrote about the latter when Teams passed Slack:

I am sure it was not a coincidence that this announcement happened in the middle of Microsoft’s annual partner conference in Las Vegas. Most of the media pays much more attention to Microsoft’s Build developer conference in the spring, but that is because writing about products is much easier than writing about ecosystems, particularly when it comes to enterprise.

Microsoft’s partner network is a truly gargantuan moat. When it comes to enterprise, it is easy to focus on the biggest companies, where Microsoft will engage directly, and challengers like Slack can build up sales forces to compete. Underneath those companies, though, are tens of thousands of smaller businesses that, even if they have IT directors of their own, rely on outside vendors to build up their technical infrastructure. Here Microsoft has invested heavily in training and equipping these vendors; critically, the company also overhauled its incentive program such that it shares its subscription revenue for Azure and Office 365 with its partners, as opposed to one-off payments for acquiring customers.

The result is that these partners are heavily motivated to offer and implement Microsoft-centric solutions: not only does everything (generally) work together, they also make more money in the process. This, then, is the context of the Teams daily active users announcement: Microsoft wasn’t simply pounding its chest, it was sending a message to its partners that pushing Teams is a winning strategy.

The key is integration.

Microsoft’s Integration

Any discussion of integration and modularization in the context of technology inevitably casts Microsoft as the ultimate example of the latter, particularly relative to Apple. In truth, though, while Windows ran on whatever hardware you wished to throw at it, the company’s software products have always been designed to work together, particularly in the enterprise. Windows Server came with Active Directory, which undergirded Microsoft Exchange, which users accessed via Outlook on their Windows computers that, of course, ran the rest of the Office suite better than anything else. It was, frankly, a pain in the rear end to try and switch out any of the pieces, which Microsoft leveraged to not only lock in its position, but also drive continual upgrades, which it used to justify subscription pricing years before the rest of Silicon Valley discovered the SaaS business model.

The combination of cloud and mobile started to break this integration apart: Microsoft’s misguided Windows-centric strategy meant that Office wasn’t available on the dominant mobile platforms, which drove companies to search out cloud-based alternatives, which made them much easier to both trial and support. That is why it was so important that Satya Nadella’s first public appearance as CEO was announcing Office for iPad, and why his greatest triumph was The End of Windows.

The end of Windows as the center of Microsoft’s approach, and the shift to the cloud, though, did not mean the end of Microsoft’s focus on integration, or its attempt to be an operating system; the company simply changed its definition of what an operating system was; Satya Nadella said at a press briefing in 2019:

The other effort for us is what we describe as Microsoft 365. What we are trying to do is bring home that notion that it’s about the user, the user is going to have relationships with other users and other people, they’re going to have a bunch of artifacts, their schedules, their projects, their documents, many other things, their to-do’s, and they are going to use a variety of different devices. That’s what Microsoft 365 is all about.

Sometimes I think the new OS is not going to start from the hardware, because the classic OS definition, that Tanenbaum, one of the guys who wrote the book on Operating Systems that I read when I went to school was: “It does two things, it abstracts hardware, and it creates an app model”. Right now the abstraction of hardware has to start by abstracting all of the hardware in your life, so the notion that this is one device is interesting and important, it doesn’t mean the kernel that boots your device just goes away, it still exists, but the point of real relevance I think in our lives is “hey, what’s that abstraction of all the hardware in my life that I use?” – some of it is shared, some of it is personal. And then, what’s the app model for it? How do I write an experience that transcends all of that hardware? And that’s really what our pursuit of Microsoft 365 is all about.

This is where Teams thrives: if you fully commit to the Microsoft ecosystem, one app combines your contacts, conversations, phone calls, access to files, 3rd-party applications, in a way that “just works”; I explained my personal experience with Teams in a December 2018 Daily Update:

Here’s the thing, though: Dropbox absolutely is better than One Drive. Google Apps are better at collaboration than Microsoft’s Office apps. Asana is better than Planner. And, to be very clear, Slack is massively better than Teams at chat. Using all of them together, though, well, it sucks: the user experience that matters for me is not any one app but all of them at once, and for the way I want to work, having everything organized in one single place is simply better (and that’s even with the normal spate of maddening Microsoft UI oddities!). In this Teams is less a chat app than it is a file explorer for the cloud generally, and Stratechery LLC specifically.

This is what Slack — and Silicon Valley, generally — failed to understand about Microsoft’s competitive advantage: the company doesn’t win just because it bundles, or because it has a superior ground game. By virtue of doing everything, even if mediocrely, the company is providing a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts, particularly for the non-tech workers that are in fact most of the market. Slack may have infused its chat client with love, but chatting is a means to an end, and Microsoft often seems like the only enterprise company that understands that.

Slack Connect

This left Slack in a very vulnerable position: Teams was “free”, supported by Microsoft’s sales teams and partner network, and, from a certain perspective, was actually easier to use. Unless your job was to chat all day, why choose Slack? In fact, that was the solution: what Slack has done over the last few years is make chat itself into a moat, not just by being better at it, but by expanding who it is you can chat with.

The key piece is Shared Channels, which officially launched in 2019, after a seemingly interminable two-year beta period. From the announcement on Slack’s blog:

Millions of people use Slack every day as a better way to get work done: with faster and more effective collaboration, deeper connections with colleagues, and seamless integrations with the apps and programs we use every day. But what about all the work that happens outside our organizations—with vendors, partners, contractors? Why compromise there?

For that, there’s shared channels, a new feature that allows Slack teams in different organizations to use Slack to collaborate together as easily and productively as they do internally. It’s officially out of beta today and available for all paid plans.

A shared channel works just like a normal Slack channel, only now connecting organizations. This means a team from Company A is communicating in the same Slack channel as their partners at Company B. New people coming into a project can readily access a project’s archive, allowing them to ramp up swiftly. Teams can easily share updates and files, loop in the right people, and quickly make decisions—all from a single place in Slack.

Shared Channels are a far more compelling feature than Slack’s attempt at a platform, particularly when it comes to accentuating the ways in which Slack is better than Teams. First, chat is the point, not integrating with toolchains that are probably different on a company-by-company basis, which lets Slack’s strengths as a chat client come to the forefront. Second, because Slack is not deeply integrated with a bunch of other applications, it is actually easier for it to horizontally connect different companies. Third, being first actually matters.

Consider Slack Connect, which the company announced late last month:

For years, Slack has been changing the way millions of people work together within their organizations. By shifting internal communication out of inboxes and into channels, teams can work more transparently with each other and get more done. But we know the work doesn’t stop at a company’s walls. That’s why today, we’re taking the next step and bringing all the benefits of Slack to everyone you work with, both inside and outside your organization. Introducing Slack Connect: a more secure and productive way for organizations to communicate together.

More than four years in the making and developed with customers, Slack Connect is a secure communications environment that lets you move all the conversations with your external partners, clients, vendors and others into Slack, replacing email and taking business collaboration to the next level…Starting today, up to 20 organizations can come together in a single Slack channel, enabling customers to bring even more of their external ecosystem into Slack—such as their entire supply chain, corporate subsidiaries or industry peers.

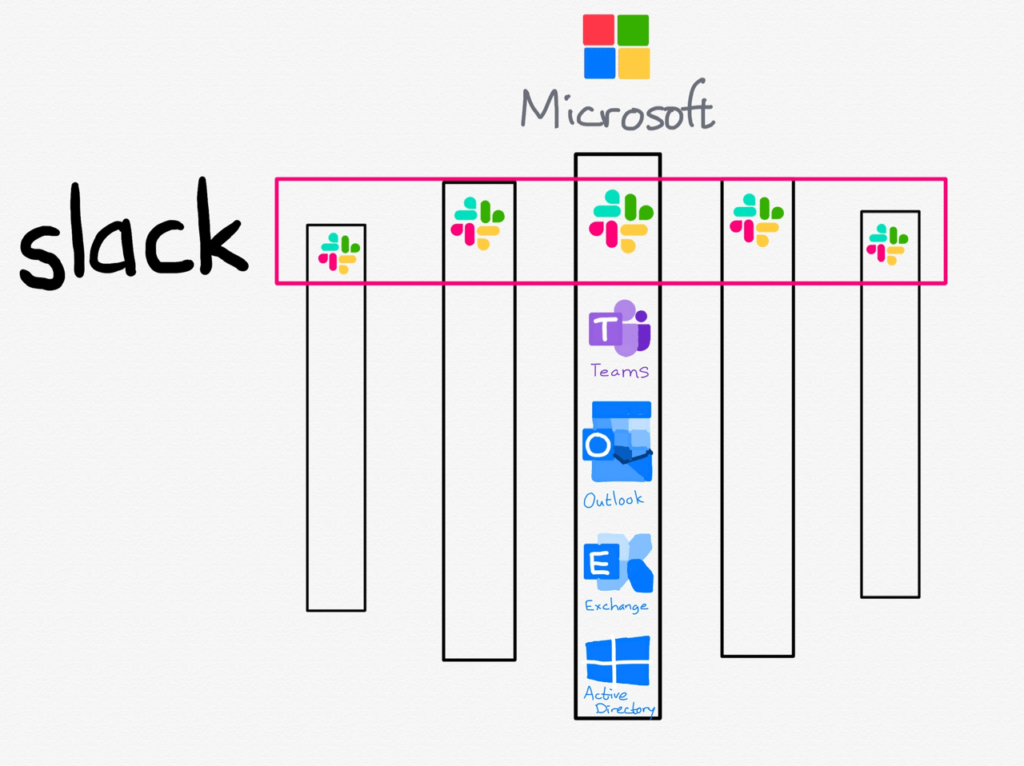

Slack Connect is about more than chat: not only can you have multiple companies in one channel, you can also manage the flow of data between different organizations; to put it another way, while Microsoft is busy building an operating system in the cloud, Slack has decided to build the enterprise social network. Or, to put it in visual terms, Microsoft is a vertical company, and Slack has gone fully horizontal:

This doubles down on all of the advantages of shared channels. The user experience of chat specifically is what matters; the only reason this is even possible is because Slack is focused on one specific part of the stack, and the more companies that take advantage of Slack Connect the more of a moat Slack has. That’s the thing about social networks: their best feature is whether or not your friends are on it, or, in this case, whether or not the companies you are working with are using Slack.

I certainly find it compelling: it is hard to imagine how the Stratechery podcast service would have been built without shared channels, which means that yes, I pay for both Microsoft 365 and Slack, and happily so. Moreover, I can’t imagine ever not paying — Stratechery LLC is already tied into 4 other companies, and that number will only go up. It appears that Slack has learned the lesson all successful companies must learn: idealistic statements — or advertisements — about building with “love” are a lot less useful than actually understanding what solutions you can build that both solve customer problems and give your product a moat in the process.

Slack’s shift into being an enterprise social network is not necessarily bad news for Microsoft; if anything it removes a potential contender for the enterprise cloud OS. It does, though, raise the question of who will actually build the modular alternative to Microsoft?

The obvious answer is Google: the company has both the resources and, in the case of G Suite, the core products to do so. The biggest obstacle is that the search company is the exception that proves the rule: Google search won simply by being better, in a market that was both desperate for what the company built, and completely open. A better search engine really was just a click away.

The problem this presents to Google’s enterprise efforts is that the company has never learned how to listen to customers, how to sell, or how to build an ecosystem. Yes, Android has as many apps as you might want, but that is more a function of just how massive the mobile opportunity is (which is why Apple can be a rent-seeking platform for developers yet have a huge ecosystem). Creating a full stack alternative to Microsoft filled with best-of-breed apps will require capabilities that Google has never really demonstrated.

For that reason, while Microsoft still needs to learn how to capture new companies, its moat with most of the enterprise market appears as strong as ever; Slack deserves credit for carving out its own.

I wrote a follow-up to this article in this Daily Update.

</div>文章版权归原作者所有。