India, Jio, and the Four Internets

India, Jio, and the Four Internets ——

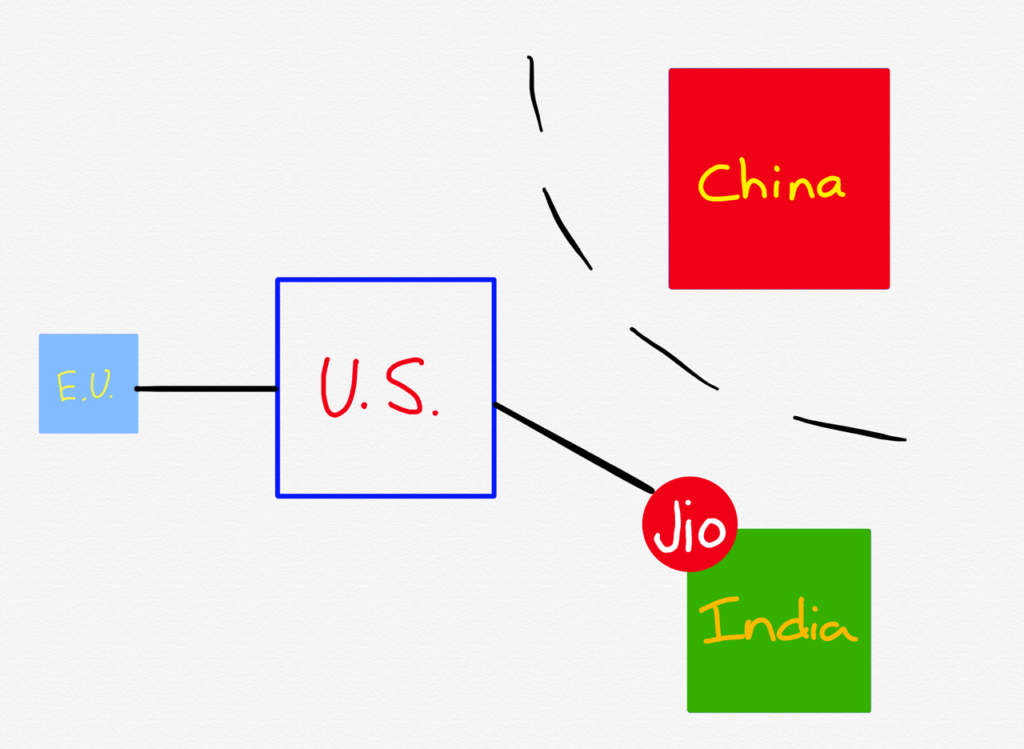

One of the more pernicious mistruths surrounding the debate about TikTok is that this will potentially lead to the splintering of the Internet; this completely erases the history of China’s Great Firewall, started 23 years ago, which effectively cut China off from most Western services. That the U.S. may finally respond in kind is a reflection of reality, not the creation of a new one.

What is new is the increased splintering in the non-China Internet: the U.S. model is still the default for most of the world, but the European Union and India are increasingly pursuing their own paths.

The U.S. Model

The U.S. Internet model is a laissez-faire one, and it is hard to argue against its effectiveness. Not only is the technology sector the biggest driver of U.S. economic growth for many years now, but U.S. Internet companies have come to dominate most of the world, conveying U.S. soft power like McDonald’s and Hollywood on steroids. There are obvious downsides to this approach: the Internet’s lack of friction both leads to Aggregators dominating markets and creates communities both good and bad.

This article, though, is primarily focused on economics and politics, and in that regard the winners and losers of the U.S.’s approach are as follows:

Winners:

- Large U.S. tech companies operate freely in the U.S., giving them a large and profitable user base to fund expansion abroad.

- New U.S. tech companies face relatively few barriers to entry, particularly in terms of regulation of content or data collection.

- The U.S. government collects the vast majority of taxes from these U.S. companies, including from revenue generated abroad, and also sees the overall U.S. view of the world exported via U.S. tech companies, while also having access to the data of non-U.S. citizens.

- U.S. citizens operate with a high degree of freedom online, although there are minimal restrictions on the collection of the data generated from doing so by private companies.

- Non-U.S. citizens operate with a high degree of freedom online, although there are minimal restrictions on the collection of the data generated from doing so by private companies or the U.S. government.

- Non-U.S. companies are free to operate in the United States without restriction, and in other countries that follow the U.S.’s approach.

Losers:

- Non-U.S. governments have limited control over U.S. tech companies, limited access to their revenues, and limited control over the spread of information.

My biases should be obvious: I definitely believe that the U.S. approach is the best one. Certainly many will quibble with the effect on new companies, given how Aggregators tend to dominate their markets, while others are focused on the collection of data; I am concerned that proposed solutions are worse than the harms, particularly given the consumer benefit of data factories. Still, as I noted yesterday, I believe the European Union Court of Justice makes a compelling case that the ability of the U.S. government to collect data from non-U.S. citizens is a serious privacy issue.

Those quibbles, though, serve to highlight a point we can all agree on: non-U.S. governments have a lot of legitimate complaints about the hegemony of U.S. tech companies.

The China Model

The driving impetus of the China model is, first and foremost, control over information. This is evidenced by the fact that not only does China control access to Western services at the network level, but also employs huge numbers of censors for the Internet within China, and expects Chinese Internet companies like Tencent or ByteDance to have thousands of censors of their own.

At the same time, the economic benefit of China’s approach for China can not be denied. China is the only country to rival the U.S. for the sheer size and breadth of its Internet companies, thanks to the combination of a massive market and the lack of competition. Moreover, this led to all sorts of innovation, as China’s leapfrog to mobile avoided the baggage of PC-assumptions that still limits many U.S. companies.

That noted, it is fair to wonder just how replicable the China model is. Smaller countries like Iran have instituted similar controls on U.S. tech companies, but without a market like China it is far more difficult to capture the economic upside of the Great Firewall. And, it should be noted, there are a lot of losers with the China model, including Chinese citizens.

The European Model

Europe, through regulations like GDPR and the Copyright Directive, along with last week’s court decision striking down the Privacy Shield framework negotiated by the European Commission and the U.S. International Trade Administration (and a previous decision striking down the Safe Harbor Privacy Principles framework), is splintering off into an Internet of its own.

This Internet, though, feels like the worst of all possible outcomes. On one hand, large U.S. tech companies are winners, at least relative to everyone else: yes, all of the regulatory red tape increases costs (and, for targeted advertising, may reduce revenue), but the impact is far greater on would-be competitors. To put it in allegorical terms, the E.U. is restricting the size of the castle even as it dramatically increases the moat.

E.U. citizens, meanwhile, are likely to see their data increasingly protected from the U.S. government, which is a win; other protections, meanwhile, seem unlikely to be particularly effective or outweigh the general annoyance and loss of relevance that comes from endless permission dialogs and non-targeted content. Moreover, per the previous point, the number of alternatives to established incumbents are likely to decrease, particularly relative to the U.S.

It also seems unlikely that European competitors will fill in the gap. Any company that wishes to achieve scale needs to do so in its home market first, before going abroad, but it seems far more likely that Europe will make the most sense as a secondary market for companies that have done the messy work of iterating on data and achieving product-market fit in markets that are more open to experimentation and impose less of a regulatory burden. Higher costs mean you need a greater expectation of success, which means a proven model, not a speculative one.

Worst of all, at least from the E.U.’s perspective, is that this approach doesn’t really have any upside for European governments. That’s the thing with rule by regulation: without a focus on growth it is harder to create win-win situations.

The Indian Model

The India market has always been a bit unique: while foreign companies have usually been unencumbered when it comes to digital goods, leading to a huge number of users for U.S. companies like Google and Facebook, and Chinese companies like TikTok, India has kept a much tighter leash when it comes to the physical layer of tech. This ranges from strong tariffs on electronics to a ban on foreign direct investment in things like e-commerce. Moreover, India has always been one of the most challenging markets in terms of Internet access and logistics.

At the same time, the Indian market is the most enticing in the world for both U.S. and Chinese tech companies, which have largely saturated their home markets. This has led to a regular number of collisions between foreign tech companies and India regulators, whether it be Facebook’s attempts to introduce Free Basics or WhatsApp payments, increasing restrictions on Amazon and Flipkart’s e-commerce operations, or most recently, the outright banning of TikTok on national security concerns.

Over the last few months, though, a way to square this circle has become apparent to U.S. tech companies in particular, and it portends a fourth Internet: invest in Jio Platforms.

The Jio Bet

Jio, the dominant telecoms network in India, is one of the all-time greatest examples of the power of building, and the outsized returns that come from betting on technology-enabled disruption. I described the economics of the bet by Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man, in an April Daily Update:

The key to understanding Ambani’s bet is that while all of the incumbent mobile operators in India were, like mobile operators around the world, companies built on voice calls that layered on data, Jio was built to be a data network — specifically 4G — from the beginning.

- 4G, unlike 2G and 3G, does not support traditional circuit-switched telephony services; voice calls are instead handled the same as any other data.

- Because everything is data, 4G networks can be built with commodity hardware in a way that 2G and 3G networks cannot.

- Because Jio was offering a data network, voice calls, which are relatively low bandwidth, were the cheapest services to offer, and capacity was effectively infinite.

To put it another way, Jio was a bet on zero marginal costs — or, at a minimum, drastically lower marginal costs than its competitors. This meant that the optimal strategy was — you know what is coming! — to spend a massive amount of money up front and then seek to serve the greatest number of consumers in order to get maximum leverage on that up-front investment.

That is exactly what Jio did: it spent that $32 billion building a network that covered all of India, launched with an offer for three months of free data and free voice, and once that was up, kept the free voice offering permanently while charging only a couple of bucks for data by the gigabyte. It was the classic Silicon Valley bet: spend money up front, then make it up on volume because of a superior cost structure enabled by the zero-marginal nature of technology.

What makes this story so compelling is the contrast to Facebook’s argument for Free Basics:

The end result is what Zuckerberg said must be done: hundreds of millions of Indians, a huge portion of them from the country’s poorest regions, were connected to the Internet. Unlike Free Basics, though, it was all of the Internet.

That actually undersells just how much better Jio is for Indians than Free Basics would have ever been: Zuckerberg had no plan for upending India’s old mobile order, where operators focused most of their investment on India’s largest cities and competed for the richest parts of society, charging so much that Andreessen could declare, with a straight face, that to not offer Free Basics was “morally wrong.” In that world, India’s poor may have had access to Facebook, but little more, since there would have been no reason for non-Free Basics companies to invest. Instead they not only have the whole Internet but companies from India to China to the United States competing to serve them.

I wrote that Daily Update on the occasion of Facebook investing $5.7 billion for a 10% stake into Jio Platforms; it turned out that was the first of many investments into Jio:

- In May, Silver Lake Partners invested $790 million for a 1.15% stake, General Atlantic invested $930 million for a 1.34% stake, and KKR invested $1.6 billion for a 2.32% stake.

- In June, the Mubadala and Adia UAE sovereign funds and Saudi Arabia sovereign fund invested $1.3 billion for a 1.85% stake, $800 million for a 1.16% stake, and $1.6 billion for a 2.32% stake, respectively; Silver Lake Partners invested an additional $640 million to up its stake to 2.08%, TPG invested $640 million for a 0.93% stake, and Catterton invested $270 million for a 0.39% stake. In addition, Intel invested $253 million for a 0.39% stake.

- In July, Qualcomm invested $97 million for a 0.15% stake, and Google invested $4.7 billion for a 7.7% stake.

With that flurry of fundraising Reliance completely paid off the billions of dollars it had borrowed to build out Jio. What is increasingly clear, though, is that the company’s ambitions extend far beyond being a mere telecoms provider.

Jio’s Vision

Last Wednesday, after announcing Google’s investment in Jio Platforms at Reliance Industries’ Annual General Meeting, Ambani said:

I would like to first share with you the philosophy that animates Jio’s current and future initiatives. The digital revolution marks the greatest disruptive transformation in the history of mankind, comparable only to the appearance of human beings with intelligence capability on our planet about 50,000 years ago. It is comparable because man is now beginning to infuse almost limitless intelligence into the world around him.

We are today at the initial stages of the evolution of an intelligent planet. Unlike in the past this evolution will proceed with a revolutionary speed. Our world will change more unrecognizably in just eight remaining decades of the 21st century, than today’s world has changed from what it was 20 centuries ago. For the first time in history mankind has an opportunity to solve big problems inherited from the past. This will create a world of prosperity, beauty, and happiness for all. India must lead this change to create a better world. For this all our people and all our enterprises have to be enabled and empowered with the necessary technology infrastructure and capabilities. This is Jio’s purpose. This is Jio’s ambition.

Friends, Jio is now the undisputed leader in India with the largest customer base, the largest share of data and voice traffic, and a world-class next-generation broadband network that covers the length and the breadth of our country…Jio’s vision stands on two solid pillars. One is digital connectivity and the other is digital platforms.

In short, Jio is determined to achieve the dream that has long eluded telecom providers in other countries: moving up the stack from fixed-cost infrastructure to high-margin services. Ambani’s vision is comprehensive:

What gives Jio a chance are three important differences from telecom efforts in other markets:

- First, Jio has created a huge portion of its addressable market; whereas a Verizon in the U.S., or a NTT DoCoMo in Japan was seeking to offer services on top of a competitive telecom market, Jio is the only option for a huge number of Indians (and for those that have options, Jio is so much cheaper because of its IP-based network that it can afford the extra costs).

- Second, instead of seeking to usurp companies like Facebook or Google that already have major marketshare in India, Jio is partnering with them.

- Third, Jio is positioning itself as an Indian champion, and the lynchpin of the Indian model.

Notice how Ambani introduced Jio’s 5G plans:

Jio’s global scale 4G and fiber network is powered by several core software technologies and components that have been developed by the young Jio engineers right here in India. This capability and know-how that Jio has developed positions Jio on the cutting edge of another exciting frontier: 5G.

Today friends, I have great pride in announcing that Jio has designed and developed a complete 5G solution from scratch. This will enable us to launch a world-class 5G service in India using 100% homegrown technology and solution. This made in India 5G solution will be ready for trials as soon as 5G spectrum is available, and can be ready for field deployment next year. And because of Jio’s converged all-IP network architecture we can easily upgrade our 4G network to 5G.

Once Jio’s 5G solution is proven at India-scale, Jio platforms would be well-positioned to be an exporter of 5G solutions to other telecom operators globally as a complete managed service. I dedicate Jio’s 5G solution to our Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi’s highly motivating vision of ‘Atmanirhbhar Bharat’.

Friends, Jio Platform is conceived with this vision of developing original captive intellectual property using which we can demonstrate the transformative power of technology across multiple industry ecosystems, first in India, and then confidently offering these Made-in-India solutions to the rest of the world.

Make no mistake: Jio’s network and its work on 5G, which takes years, was by definition not motivated by a phrase Prime Minister Modi first deployed two months ago. Rather, Ambani’s dedication hinted at the role Jio investors like Facebook and Google are anticipating Jio will play:

- Jio leverages its investment to become the monopoly provider of telecom services in India.

- Jio is now a single point of leverage for the government to both exert control over the Internet, and to collect its share of revenue.

- Jio becomes a reliable interface for foreign companies to invest in the Indian market; yes, they will have to share revenue with Jio, but Jio will smooth over the regulatory and infrastructure hurdles that have stymied so many

What is fascinating about this approach is that the list of winners and losers gets pretty muddled pretty quickly. On one hand, Jio brought the Internet to hundreds of millions of Indians that would never have had access, and the benefits of that investment are only going to increase as Jio’s services and partnerships come on line. On the other hand, locking in a monopolistic player, particularly in the context of a government that has shown a desire for more control over the flow of information is a real downside.

The economic outcomes are just as muddled. Monopolies always have deadweight loss; then again, if an efficient market means that all of the profits flow to Silicon Valley, why should India particularly care about efficiency? In a Jio-mediated market it is U.S. tech companies that make less than they would have, and not only does India collect more taxes along the way, Jio’s vision of being a national champion abroad could be a huge win for India in the long run.

The Indian Counterweight

It is increasingly impossible — or at least irresponsible — to evaluate the tech industry, in particular the largest players, without considering the geopolitical concerns at stake. With that in mind, I welcome Jio’s ambition. Not only is it unreasonable and disrespectful for the U.S. to expect India to be some sort of vassal state technologically speaking, it is actually a good thing to not only have a counterweight to China geographically, but also a counterweight amongst developing countries specifically. Jio is considering problem-spaces that U.S. tech companies are all too often ignorant of, which matters not simply for India but also for much of the rest of the world.

Still, Facebook, Google, Intel, Qualcomm, et al should proceed with their eyes wide-open: they are very much a means to an end for a company and a country that is on its own path. That is not to say these investments are not a good idea — I think they are — but India’s path is perhaps a more populist and nationalistic one than many Americans would prefer. Still, it is less antagonistic to Western liberalism than the Chinese Communist Party, and again, an important counterweight.

The only question left, then, is whither Europe, and frankly, the picture is not pretty:

What differs Europe’s Internet from the U.S., Chinese, or Indian visions is, well, the lack of vision. Doing nothing more than continually saying “no” leads to a pale imitation of the status quo, where money matters more than innovation.

I wrote a follow-up to this article in this Daily Update.

文章版权归原作者所有。