The Summer Of Menace

(A protestor tries to put out a fire in front of the Mark O. Hatfield U.S. Courthouse in Portland, Oregon, on July 22, 2020. By Paula Bronstein / Washington Post)

There’s one thing I better understand after reading and researching for this essay on plagues through history. It is that epidemics like the one we’re in cannot be seen as merely medical events. Diseases like cancer or Parkinsons or hypertension are medical events. Plagues are social and cultural and political events. (The very word “epidemic” is derived from the Greek epi , meaning “among,” and demos , “ the people”.) Unlike other diseases, epidemics require concentrated groups of humans to survive and prosper, which means they rely on our social interactions, our cultural traditions and our political systems to transmit themselves. And in that transmission, they insinuate themselves into every nook and cranny of our lives and psyches—from sex to shopping, from work to religion, from politics to journalism—and thereby alter them.

When people look back on this surreal election year, I suspect they will see plague as the core actor. If you take a normal, functioning society and then force it to go underground for months, freezing it in place, forcing its members into long and unnatural mutual isolation, suspending the usual ways in which people make a living, ratcheting up financial insecurity … well, that’s a recipe for serious social upheaval. And that’s what you find everywhere in history that you look. An epidemic is not something a society can compartmentalize. It’s part of everything. Some, usually the wealthy, can avoid the worst, but even they are part of a broader world undergoing a profound upheaval. The bell tolls for them in the end as well.

In past epidemics, tackling the physical illness itself absorbed, and thereby dissipated, a huge amount of human energy. In worlds without advanced medicine, people faced the gory reality and terror of plague every single day, and that naturally penetrated their consciousness first and foremost. They walked over corpses in the street, whereas we scan graphs in the New York Times. They often had no idea what was happening to them, and we have a churning scientific complex, forever finessing our microbial understanding. They were usually helpless. We have medical treatments constantly improving, and a vaccine well under way.

And they confronted worse. Covid19 just isn’t as physically grotesque or terrifying as previous plagues. Take the most recent major event, the 1918 flu. By this time in the summer of 1918, what had been a relatively mild flu in the spring began to mutate into something much worse. Modern ventilators didn’t exist. As a victim began to lose oxygen, his face turned mahogany, then blue, then black “until it is hard to distinguish the colored men from the white,” as an army doctor wrote. The blackness started at the extremities and slowly covered the entire body, so you could actually watch the illness take over, like an inkblot on a napkin. The corpses had grossly distended chests, from lungs filled with pus and blood and a “watery pink lather”, as Laura Spinney notes in her study, Pale Rider . It was sometimes hard to cram the inflated body into a casket. Projectile nose-bleeds were common. Teeth and hair fell out. Delirium and dementia were sometimes features. And the flu struck quickly—so that you sometimes saw people just collapsing in the streets.

We are, mercifully, in a much better place. But it strikes me that this medical achievement doesn’t resolve the psychological trauma, the suspension of normality, the anxiety of an invisible enemy. It merely diverts it away from the illness itself toward broader social and political grievances. I don’t think you can fully explain the sudden increase in intensity of the social justice cult, for example, and its explosion in our streets and in our media in the last couple of months, without taking account of this. I don’t just mean the pent-up plague-driven frustration of young people, who, often forced to live at home with their parents, took the opportunity to finally get out, get together and do something, after the horrifying murder of George Floyd. I mean the more general frustration and despair of a generation with a gloomy and unknowable economic future—suddenly finding shape and voice in a simple, clarion call to reshape all of society.

I wrote about the Flagellants in the essay —a new group of fanatical, radical penitents who challenged and mocked the church authorities during the Black Death, whipping themselves bloody in large crowds across Germany, calling everyone to account for their sins. It’s the same dynamic now: a movement to use a plague to cleanse ourselves of the past and indict the entire community for its iniquity. Perhaps more analogous are the Lollards in England, who formed a deeply anti-clerical, Biblically-based, spiritually-focused movement in the wake of the Black Death that presaged the Reformation to come. These movements and the current wave of revolt share a combination of intense zeal and transformational ambition. They also share an economic and social context: a hefty section of the society is dislocated and anxious, work is unavailable, the future is highly uncertain, poverty is spreading, and criminality and violence in our cities are rising.

This, in turn, can alienate many equally stressed out law-abiding citizens, who are just as vulnerable, but haven’t yet joined the cult. Revolts, if they seem to go too far, can summon up a classic 1968-style backlash. Victims of a new crime wave can argue back. The older generation may see the destruction of monuments and statues from the past a step too far. Visceral responses to scenes of violence and mayhem can rally the mainstream against change. Plagues, remember, are not unifying events; they often split the seams of societies, and the longer they go on, the deeper the divides and the greater the mayhem. In a society as deeply tribalized as ours, zeal cuts both ways, as we’re beginning to see in right-wing media.

All of which is a highly combustible situation, bristling with menace. What Trump has been doing since the Mount Rushmore speech —stupidly dismissed by woke media —is to try and cast this election as a battle between anarchy and the forces of law and order, between a radical dystopia laced with violence and the America we know. He’s trying to jujitsu the plague-fueled revolt into a winning campaign issue. He can’t exactly run on his record of double digit unemployment and an epidemic raging out of control. So this is his instinct. And politically, it’s not a bad one. In an environment where people are afraid and uncertain, authoritarianism has an edge. The more some cities descend into lawlessness and violence this summer, the edgier, and more popular, that performative authoritarianism could get.

Sending armed federal agents to cities against the wishes of state authorities is bound to inflame the situation further, as we’ve seen in Portland. Federal agents arresting people without probable cause of any crime—as appears to have happened—is an obvious abuse of power. Blowing past the much-touted Tenth Amendment is not exactly in line with any conservative principles. And deploying these troops for a made-for-television drama to bolster Trump’s campaign is another reason this man needs to be defeated this November.

But it’s nonetheless also the case that most of Trump’s initiative is narrowly tailored to be (just) within the letter of the law, if not its spirit. And the core reason for the deployment—ongoing vandalism and destruction of federal buildings like the Court House assaulted by protestors in Portland—is a defensible one. It’s also true that in several major cities, violent crime has been surging both before and after the BLM protests, as the police have suffered a drop in morale and as retirements are way up . Shooting incidents were up 56 percent in Milwaukee over last year’s totals earlier this month, and up 54 percent in Philadelphia. Chicago’s homicides are up 39 percent— which may explain why the overwhelmed Mayor, Lori Lightfoot, agreed to accept federal help this week—without allowing direct federal law enforcement on the streets. In New York City, there were 205 shooting incidents in June , a figure last seen in 1996, a quarter century ago. I keep seeing videos of mayhem in the streets there. It’s hard to judge how typical or atypical these scenes are—but you can be sure you’ll be seeing a lot of them on Fox News night after night, and showing up in your FaceBook and Twitter feeds 24/7.

And it's worth remembering that most of the lives being lost here in this national wave of gun violence belong to African Americans. In one particular incident in DC, when an eleven-year-old boy was shot dead at a July 4th “Stop-The-Violence” cookout, his grandfather spoke for many who don’t get much of a hearing in the current moment: “We see all these protests only when an officer hurts a black person. Where are the Black Lives Matter people when black people are hurting black people?” BLM does care about such murders, of course, but the anger here is real. So is the human carnage.

In this context, “defunding the police” is not always good politics. And some white swing voters leaning toward Biden may become, if this continues or intensifies, less worried about Trump than this human toll. I should add that I think that so far, the BLM protestors have been able to shut down most of the worst violence and looting and murder, and have thereby kept the moral high ground. And Biden has also been shrewd in not taking any anti-police bait. But these situations are dynamic. They escalate easily. There is no real control of the rhetoric of extremists. And plagues stir everything up.

I may be worrying too much about the effect of this on the election, as Trump’s abject failure to control the virus remains front and center. He’s still likely to lose, absent a major surprise. But plagues are highly divisive and highly unpredictable. Trump, his back against the wall, may, in fact, be at his most reckless, gambling on escalating tribalism in a culture already unsettled by a tenacious virus. He will do everything to provoke an over-reaction, and escalate the conflict. The rest of us should do everything we can to calm it down.

Phoenix, Arizona, 5.30 pm

In Defense of J.K. Rowling

We’re used to public apologies by now, but this one is a little different. It comes from a magazine for schoolchildren in England, called “The Day”. It reads:

“We accept that our article implied that … J K Rowling … had attacked and harmed trans people. The article was critical of JK Rowling personally and suggested that our readers should boycott her work and shame her into changing her behaviour … We did not intend to suggest that JK Rowling was transphobic or that she should be boycotted. We accept that our comparisons of JK Rowling to people such as Picasso, who celebrated sexual violence, and Wagner, who was praised by the Nazis for his antisemitic and racist views, were clumsy, offensive and wrong … We unreservedly apologise to JK Rowling for the offence caused, and are happy to retract these false allegations and to set the record straight.”

The Day had been referring to JK Rowling’s open letter on trans issues, which you can read in its entirety here and judge for yourself.

I have to say it’s good to see this apology in print. It remains simply amazing to me that the author of the Harry Potter books, a bone fide liberal, a passionate feminist and a strong supporter of gay equality can be casually described, as Vox’s Zack Beauchamp did yesterday , as “one of the most visible anti-trans figures in our culture.” It is, in fact, bonkers. Rowling has absolutely no issue with the existence, dignity and equality of transgender people. Her now infamous letter is elegant, calm, reasonable and open-hearted. Among other things, Rowling wrote: “I believe the majority of trans-identified people not only pose zero threat to others, but are vulnerable for all the reasons I’ve outlined. Trans people need and deserve protection.”

She became interested in the question after a consultant, Maya Forsteter , lost a contract in the UK for believing and saying that sex is a biological reality. When Forsteter took her case to an employment tribunal, the judge ruled against her, arguing that such a view was a form of bigotry, in so far as it seemed to deny the gender of trans people (which, of course, it doesn’t). Rowling was perturbed by this. And I can see why: in order either to defend or oppose transgender rights, you need to be able to discuss what being transgender means. That will necessarily require an understanding of the human mind and body, the architectonic role of biology in the creation of two sexes, and the nature of the small minority whose genital and biological sex differs from the sex of their brain.

This is not an easy question. It requires some thinking through. And in a liberal democracy, we should be able to debate the subject freely and openly. I’ve done my best to do that in this column , and have come to many of the conclusions Rowling has. She does not question the existence of trans people, or the imperative to respect their dignity and equality as fully-formed human beings. She believes they should be protected from discrimination in every field, and given the same opportunities as anyone else. She would address any trans person as the gender they present, as would I. Of course. That those of us who hold these views are now deemed bigots is, quite simply, preposterous.

Where Rowling and I draw the line is saying that a trans woman is in every single respect indistinguishable from a natal woman. We believe that a natal man who is a transwoman, for example, cannot have a vagina exactly as a natal woman does. That’s all. And that is objectively true. Note also that this has no impact whatever on how someone should be treated by society or under the law. A transwoman can and should be treated exactly as a woman, even if she isn’t in every single respect a woman.

There are a few areas where this becomes a problem for some: a) restrooms, b) sports, and c) shelters for abused women. On a), I have zero issues with trans women with penises using the women’s room. I know some worry that creeps simply posing as transwomen could exploit this in order to gain access to children. But I have yet to see such a case in reality. It should be simple: just use a stall and mind your own business. On b), sports is different, because the physiology of male and female bodies is, by virtue of our species’ reproductive strategy, bimodal, and in sports reliant on strength and size and speed, no co-ed contest can be fair. And the last issue c) is about whether women who are in shelters for those who have been abused by men should be allowed spaces where no actual penises, even if attached to women, are around. On this difficult third area, I defer to abused women on the question of shelters. And here’s the thing: Rowling is one such woman. She told her own story of marital abuse in her letter, with a disarming honesty that surely should evoke engagement, rather than vilification.

It pains me to see where this debate has gone. There’s so much common ground. And I do not doubt that taking into account the lived experiences of trans people is important. But if we cannot state an objective fact without being deemed a bigot, and if we cannot debate a subject because debating itself is a form of hate, we have all but abandoned any pretense of liberal democracy. And if a woman as sophisticated and eloquent and humane as J K Rowling is now deemed a foul bigot for having a different opinion, then the word bigotry has ceased to have any meaning at all.

Jerusalem, Israel, 5 pm

Pining For An Analog World

In the department of plague-isolation viewing, I’ve found myself deliriously lost in HBO’s new series, Perry Mason . By lost, I mean both confused by the disjointed, convoluted plot and immersed in the world of the 1930s the series creates. Forget everything you think you know about Perry Mason. Try not to think of Raymond Burr. Just sink into a bath of noirish Los Angeles in the Great Depression and let the nostalgia bubbles reach your chin. If you’re not entirely sure what’s going on—which I suspect is quite difficult even without a freshly packed pipe of Indica—the ambiance and the performances carry you forward.

The broodingly sexy Matthew Rhys as Mason—aloof, understated, drunk half the time—staggers through the first few episodes as a street-level private detective, until, one night, he gets riled up about a case and delivers an impromptu defense of the necessity of justice that reveals a whole new man—and future star lawyer. John Lithgow plays a character—the gruff, old, bankrupt, good-hearted lawyer, E.B. Jonathan—that could almost have been written solely for him. E.B.’s assistant, played by Juliet Rylance, and a black street cop, played hauntingly by Chris Chalk, help us see the world of the Depression through the eyes of a secretary and through the lens of segregation. The meticulousness of the acting is as crisp as the evocation of a distant past. It’s become a highlight of my week.

More and more in this epidemic and political swirl, I’ve felt the need to read about and watch recreations of recognizable, complicated human beings in the past. Maybe it’s because I’m exhausted, even flattened, by the present, and want to be taken away—and dreaming of the future seems, well counter-productive. Maybe I’m simply rattled by the pace of change and want to remember what I delude myself into thinking were stabler times. I’ve become fixated, for example, on the phones in Perry Mason: the way the characters tap the line to clear it, the way they dial them, the way they seem instantly to remember the numbers, the brief conversations with an actual operator, the dramatic hangings up—and the vastly greater plot possibilities because people can be out of touch, or miss a call, or have no access to a public phone.

And then there’s the wonderfully clunky transportation, as cars began to dominate the market, as trams ferried people around in Los Angeles, and as a trip from L.A. to San Francisco was most commonly done by train. But most of all, I find myself gazing at the simple habits of meeting and greeting, open restaurants and crowded rooms, mask-free hustle and bustle, the care-free kisses and hugs, and the sense of a country and a state just beginning a long, astonishing arc of growth.

It’s not that Perry Mason glamorizes the past: we witness, for example, a corrupt District Attorney seeking re-election, and a press corps of vulture-like rapacity. It’s that it portrays an analog, plague-free world in a high-tech, viral age. And I miss it.

See you next Friday.

Dissents Of The Week

One amazing truth about the Dish in-tray: you kept writing us for five years, even when we didn’t really exist. And Covid19 saw a new blip of correspondence. Here’s a sampling of Dishhead consciousness. A reader on April 25 wrote about the isolation disease can foster:

I’m 39 and I had a stroke about a decade ago, from getting a bacteria infection from IV drug use. It makes it hard for me to concentrate, and certainly to be employed for an extended period of time. Most importantly, it makes it hard to string together a few sentences, without feeling hugely embarrassed about the quality of my speech; I still suffer from aphasia. Losing the ability to speak, or communicate through language, is devastatingly isolating.

I’ve been working from home for a couple of years, and 99.99% of that was totally alone. In the past couple of months, I’ve heard “I love the quarantine! Why did we ever have to leave the house for work?” Maybe these people live with a significant other, or have a dog, that serves as a buffer from the loneliness that I feel daily. Who knows? I know I’m depressed all of the time, and a huge contributing factor is my loss of the ability to connect with people in real time.

I just wanted to let you know that there are lots of us out there—those who appreciate the burden of isolation for an individual. This is “Bowling Alone” at a grand and immediate scale.

The world of sickness and the world of health can be very far apart at times. After reading my May 15 column, “The Very First Pandemic Blogger,” a reader wrote:

Loved your piece on Pepys. Here is my favorite quote of his—when I taught college for 10 years it drove the woke students mad, and it’s almost as good as Orwell on the front of one’s nose: “We should be most slow to believe that we most wish should be true.”

Another reader went there:

You mentioned wearing a mask when going out and that you have bad lungs. The mask won’t well work unless it seals against your skin, so please consider shaving your beard, so the mask hits your skin.

Trimmed, not shaved. Other readers began to lobby for a Dish return:

There are lots of us who would subscribe to your own publication if you choose to go that route. I’m sure you know this, and I’m sure there are many issues involved. But the thought of you being edited by the woke youngsters is truly depressing, so I had to say it.

On June 7, when the national protests were in full swing, a self-described Dishhead in Belgium implored, “please come back to your readers”:

I have been following you for the past 10+ years. I understood that you had to slow down. I wasn’t really happy with the move to NYMag, but at least I could read three of your reflections every week—which, living in Europe, usually meant I was finishing the week late at night with your Friday column. But after this unbelievable week in the U.S., where I followed closely different news and commentary streams, I was impatiently waiting to cap it off with your take on the events—only to find out that it wasn’t going to appear.

Andrew, you don’t need this job. You still have long-time readers who would be happy to subscribe to an independent blog, even just for weekly articles, if you don’t want to write more.

Another reader two weeks later, out of the blue, said he was “pining for the Dish”:

I hope you still read your emails. The unique strength of the Dish, and the reason why I read it daily for years, was your curated reader feedback, counter-feedback and counter-counter-feedback, which made for a complex, informative and lo-and-behold opinion-challenging experience. I miss it.

Well, here we are again. Now, a dissent. A reader “was taken aback” by my June 26 column, “You Say You Want a Revolution?”—about the destruction of statues around the country:

Your attempt to highlight the fringe as somehow dictating and representing the, at least, plurality of Americans on the left is disingenuous at best. Confederate statues were put into place about 70 years after the Civil War and was a direct attempt to promote and preserve white supremacy and anti-black racism. The lionization of these Confederate symbols, including the Confederate flag, were and are blatant racist promotion. Yes, some of the fringe go too far … but, that’s almost always the case. Every single one of these statues need to be torn down and the Confederate flag should be just as shunned as the Nazi Swastika.

The difference between today’s “liberals” and “right wingers” is that the fringe and crazies have literally taken over the Republican Party, while they have little traction in the Democratic Party. This distinction is fairly plain to see, and I am stunned by your demagoguery of today’s column.

I agree that most of the Confederate statues should go, especially those erected decades later precisely to celebrate a white supremacist past, but only through a lawful, democratic process. Another dissenting reader:

In response to your latest column, I’d like to propose a simple thought experiment. Let’s say that 155 years ago in the U.S., gay people could be bought and sold as property. They were routinely raped, tortured, brutalized, and for centuries forced to work for no money by straight people. They are property. Half of the U.S., the South, liked this arrangement, and they fought and lost a civil war so they could continue brutalizing gay people in this manner.

The South had their heroes in the war. Because the North valued the straight people in the South more than any gay people, the North allowed the South to build monuments to these “heroes” and even allowed the South for another 100 years to keep brutalizing gays and treating them as servants. Up until the present day, the North continued to value the straights in the South more than the tortured, brutalized gays.

Today you are a gay person in the South. You see heroic monuments of the people who savagely degraded gay people who came before you, who were your ancestors. For the first time in centuries, the North is suggesting that maybe these celebrations of your tormentors weren’t really appropriate.

Then some British straight dude starts writing columns telling you take it easy, chill out, and preserve this important history. What do you do? What do you feel?

Point taken. But my position is not that they should all stay—just that violence is not the way to do it. I’m an Irish-Catholic from England. Outside Parliament, there is a statue of Oliver Cromwell, who waged a genocidal war against Irish Catholics when he was Protector. Do I want it taken down? No. From a reader named Karen:

God only knows, I support BLM and reforms to policing. (I had a nice “Karens Against Racism” sign at a protest.) But I saw how Ibram Kendi and one of his allies publicly shamed Allison Stanger at a Bard conference last year because she said something positive about merit, and that she showed “white fragility” when she defended herself. Apparently, she should have just trusted that they knew the truth and she did not, professed gratitude for the correction, and promised to educate herself further.

I think of how French historian Marc Bloch wrote his brilliant volumes, Feudal Society , while working for the Resistance and hiding out from the Nazis. The book wasn’t on fascism; it was on feudalism. Sometimes, can the most political thing you can do be to resist the political? I wonder if we can’t have our own Benedict Option for people who don’t want to go along with the likes of Ibram Kendi and Robin DiAngelo.

Call it the Montaigne Option. There’s a wonderful passage in Sarah Bakewell’s biography of Montaigne, How to Live , that speaks to this. The 16th-century Montaigne, though the mayor of Bordeaux for a period, largely disengaged from the politicking and religious warfare between the Catholics and Protestants in France:

Books have been written promoting Montaigne as a hero for the twenty-first century; French journalist Joseph Macé-Scaron specifically argues that Montaigne should be adopted as an antidote to the new wars of religion. Others might feel that the last thing needed today is someone who encourages us to relax and withdraw into our private realms. People spend enough time in isolation as it is, at the expense of civil responsibilities.

Those who take Montaigne as a hero, or as a supportive companion, would argue that he did not advocate a “do-as-thou-wilt” approach to social duty. Instead, he thought that the solution to a world out of joint was for each person to get themselves back in joint: to learn “how to live,” beginning with the art of keeping your feet on the ground. You can indeed find a message of inactivity, laziness, and disengagement in Montaigne, and probably also a justification for doing nothing when tyranny takes over, rather than resisting it. But many passages in the Essays seem rather to suggest that you should engage with the future; specifically, you should not turn your back on the real historical world in order to dream of paradise and religious transcendence. Montaigne provides all the encouragement anyone could need to respect others, to refrain from murder on the pretense of pleasing God, and to resist the urge that periodically makes humans destroy everything around them and “set back life to its beginnings.”

Sometimes, maybe just looking out your window helps. A reader asked on March 25, a few weeks into the Covid crisis:

Good time for a view from your window? Have you thought about a special apocalypse version of VFYW? People have a lot of time on their hands.

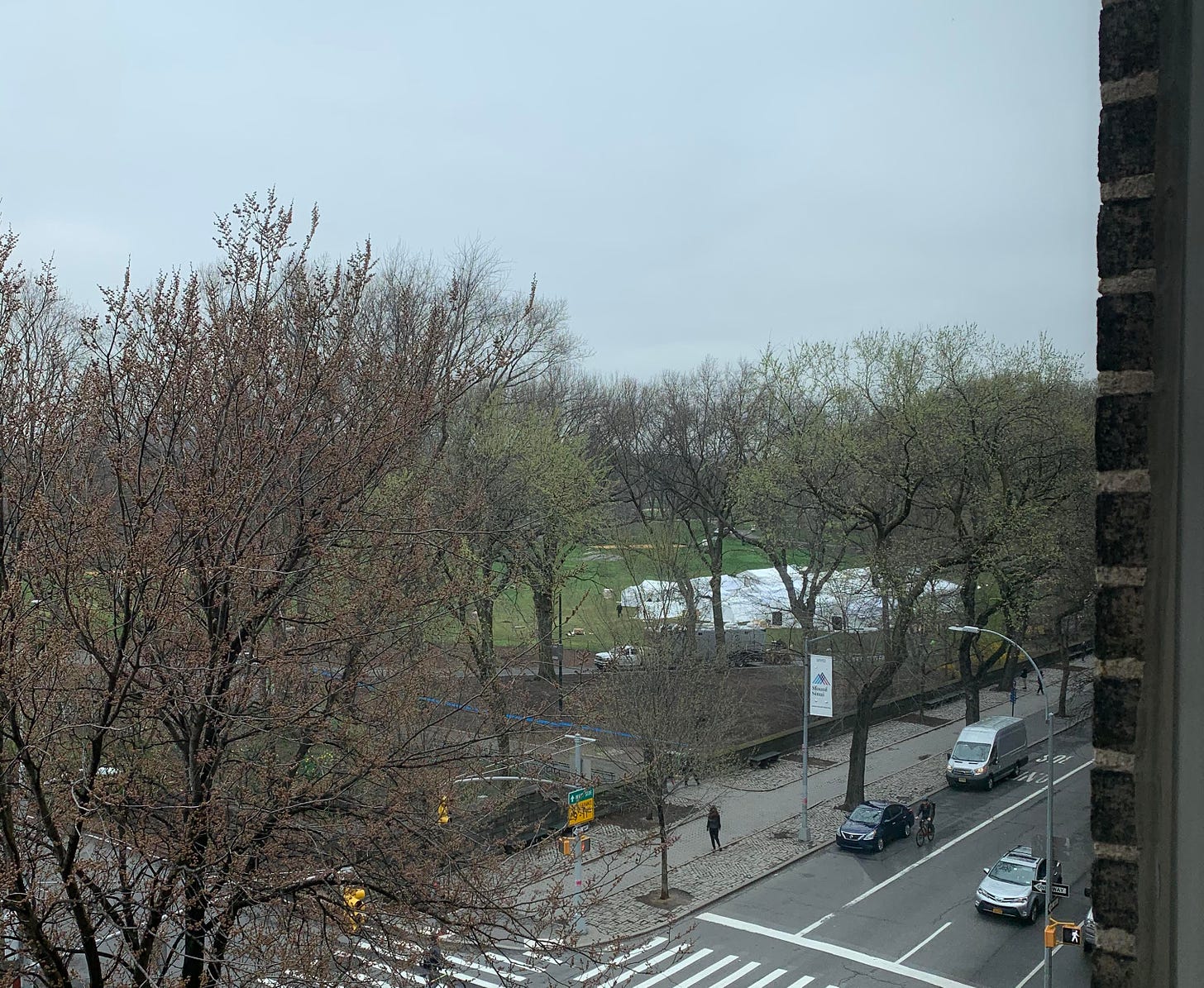

Another reader five days later sent an ominous view of a “newly-erected field hospital in Central Park, outside Mt Sinai Hospital, Manhattan, 9:20 am”:

A reminder about submitting window views: provide the photo, the time of day, and the place. We need all three to post one. Another reader is craving some friendly competition:

In these troubled times, I need the window contest. It got me through a very unpleasant job. Every week I’d turn to that simple photo. It kept my mind on a normal world, a normal street, a normal person looking out a window. I miss it terribly.

Your wish is granted! Here’s the first entry in TWD’s View From Your Window Contest:

Yes, it’s a tough one, but there’s a meta clue. Be sure to email entries to contest@andrewsullivan.com . Please put the location—city and/or state first, then country— in the subject heading , along with any description within the email. If no one guesses the exact location, proximity counts. You have until Friday at noon, and we’ll post the results that day. Happy sleuthing!

|

|

文章版权归原作者所有。