Apple, Epic, and the App Store

Apple, Epic, and the App Store ——

Circuit Judge Consuelo M. Callahan, in last week’s decision by the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, reversing the District Court’s ruling that Qualcomm was guilty of antitrust violations, opened her opinion thusly:

This case asks us to draw the line between anticompetitive behavior, which is illegal under federal antitrust law, and hypercompetitive behavior, which is not.

This is, admittedly, a distinction I have not seen before, but it is perhaps a useful one, for the simple reason that being a successful business by definition means being anticompetitive: without some sort of differentiation and/or superior cost structure any sort of margin a business has will be competed away, and so preserving that differentiation and/or cost structure — being anticompetitive — should be the goal of any business. The distinction Callahan was drawing, though, is necessary if you interpret “anticompetitive” as being “illegal”: businesses should compete, but they should not break the law along the way.

What makes this distinction particularly challenging is that the question as to what is anticompetitive and what is simply good business changes as a business scales. A small business can generally be as anticompetitive as it wants to be, while a much larger business is much more constrained in how anticompetitively it can act (as a quick aside, for the first part of this essay I am painting in broad strokes as far as questions of specific legality go). The specific case of Apple and the iPhone raises an additional angle: should the importance of the market in the question make a difference as well?

Apple’s Vertical Integration

Apple’s business model, which uses software to differentiate hardware, is designed to be anticompetitive. The company has traditionally made its money by selling physical devices which run Apple’s proprietary operating systems; its device-manufacturing competitors, meanwhile, have had to rely on an operating system that they could license, primarily Windows for PCs, and Android for mobile devices. They cannot license macOS or iOS.

What is funny about calling this strategy “anticompetitive” is that it wasn’t that long ago that most pundits were sure Apple was anti-competing themselves into the ground. When Stratechery started in 2013, the media was filled with predictions of the iPhone’s imminent demise at the hands of Android: there were simply too many other manufacturers making too many smartphones at too many price points that Apple could not or would not match, which would inevitably lead to developers fleeing iOS and Apple fighting for its life.

The problem with these predictions, as I wrote in What Clayton Christensen Got Wrong, is that they drastically undervalued the experience of using Apple’s integrated products.

The business buyer, famously, does not care about the user experience. They are not the user, and so items that change how a product feels or that eliminate small annoyances simply don’t make it into their rational decision making process. Again, though, Christensen’s research is tilted towards business buyers. Critically, this includes the PC. For the most of its history, the vast majority of PC purchasers have been businesses, who have bought PCs on speeds, feeds, and ultimately, price…

I attributed Apple’s ability to eliminate many of those small annoyances to its vertical integration, which had long been out of fashion:

The traditional business theory about vertical integration rests on the costs and controls…The issue I have with this analysis of vertical integration…is that the only considered costs are financial. But there are other, more difficult to quantify costs. Modularization incurs costs in the design and experience of using products that cannot be overcome, yet cannot be measured. Business buyers — and the analysts who study them — simply ignore them, but consumers don’t. Some consumers inherently know and value quality, look-and-feel, and attention to detail, and are willing to pay a premium that far exceeds the financial costs of being vertically integrated.

One thing that is worth noting is that Apple has only ever integrated part of its value chain, particularly once it started manufacturing in China. A Mac, for example, looks something like this:

In this view Apple integrates hardware made with industry-standard components and macOS, providing a platform for even more app developers. Of course, this view of the Mac will soon be obsolete: Apple computers will soon come with Apple’s own chips, which is to say that the company is backward-integrating into one of its most important components. This is, as far as I can tell, seen as a good thing: Apple has both demonstrated its ability to build fast chips and to integrate those chips with its operating system; no one feels especially bad for Intel, particularly since the company had its own near-monopoly for decades.

App Store Integration

Of course iPhones have already been using Apple’s own chips for a decade; what has always made the iPhone different than the Mac, though, is the degree to which Apple has forward-integrated into the app ecosystem. What is critical to understand is that this integration proceeded in parts, and that those parts build on each other.

App Store Part One: Installation

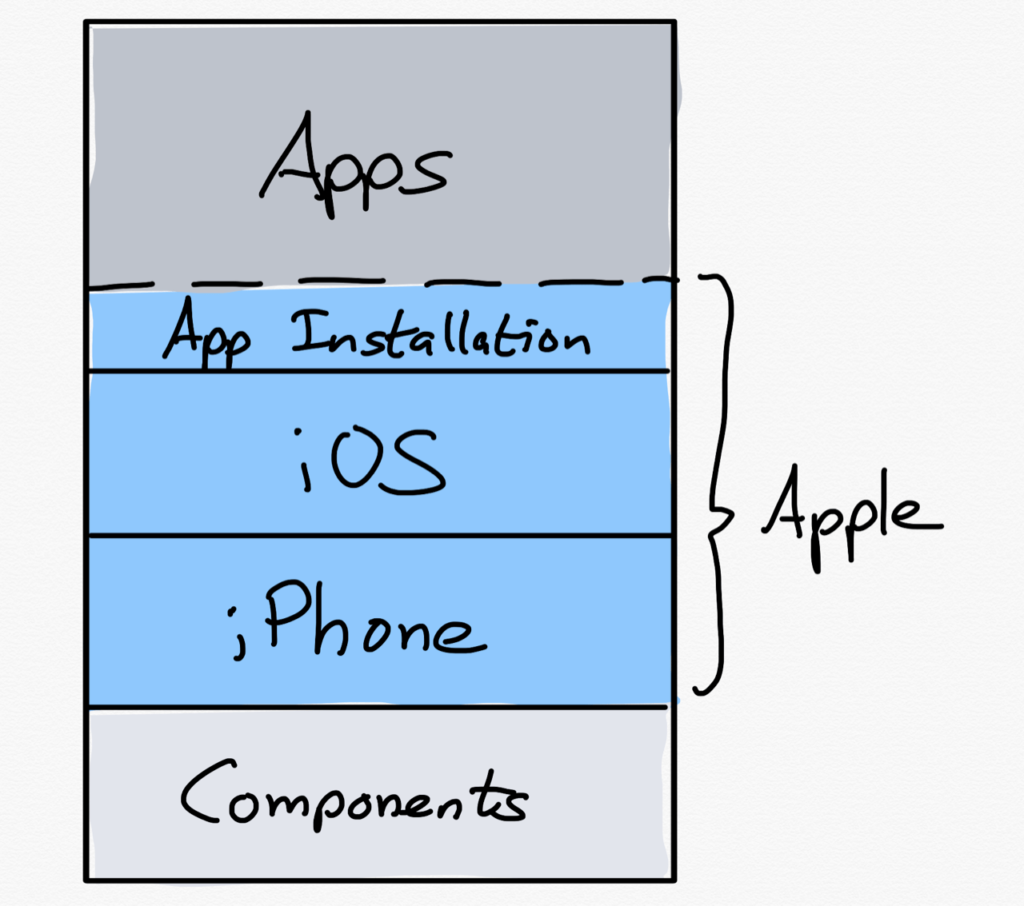

Start with app installation: because Apple controls the operating system, it controls what apps can or cannot be installed on the device. iOS will only run apps have permission from Apple (this permission is ultimately enforced by Apple’s hardware), and Apple grants this permission via the App Store. To put it in the context of the value chain, Apple leverages its integration of hardware and software to control app installation:

It is essential to note that this forward integration has had huge benefits for everyone involved. While Apple pretends like the Internet never existed as a distribution channel, the truth is it was a channel that wasn’t great for a lot of users: people were scared to install apps, convinced they would mess up their computers, get ripped off, or accidentally install a virus.

The App Store changed all of that: Apple effectively extended the trust it had earned with users over the years to all developers in the App Store. Users could install whatever they wanted, confident the app would not mess up their phone, rip them off, or be a virus. This by extension meant that the addressable market was far larger for app developers than the PC was, even though it would be several years before smartphones had a larger installed base than PCs. And this, of course, brought benefits to Apple:

This was the combination of integration and modularity at its absolute best: Apple leveraged its control to create a better market that benefited everyone.

App Store Part Two: Payment Processing

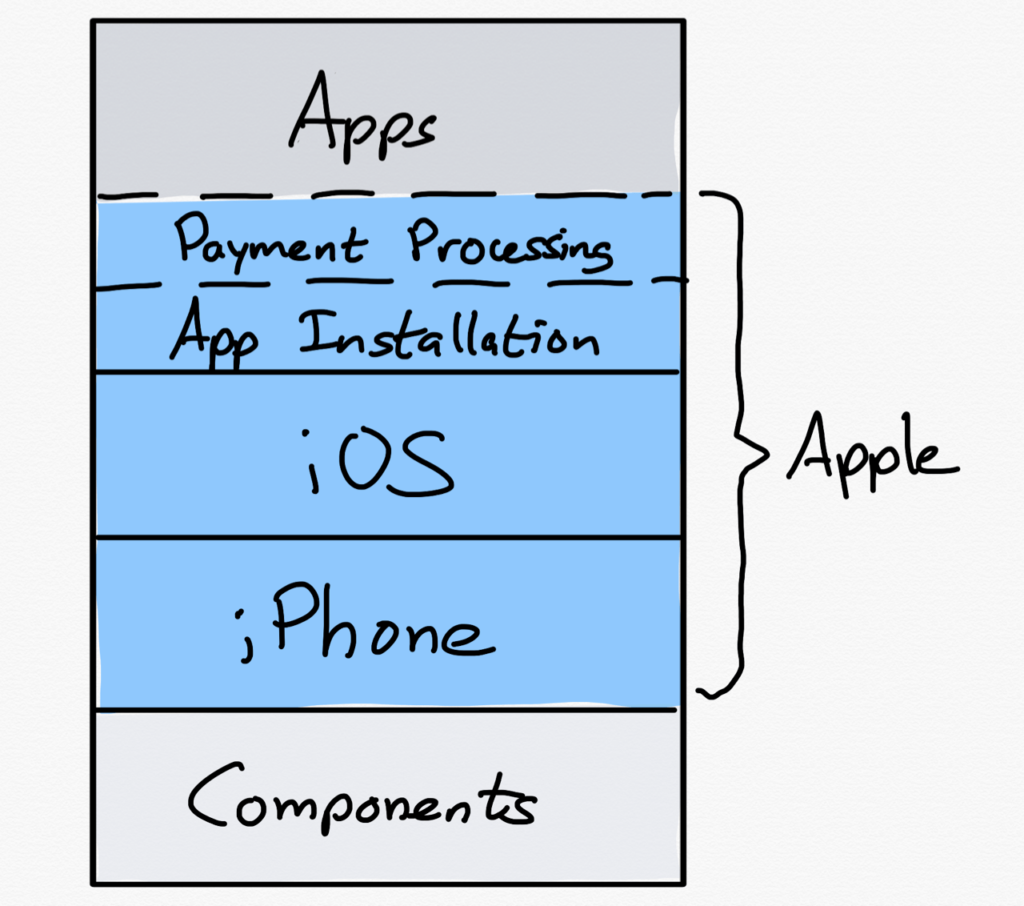

Given the fact that Apple controlled app installation, it was a natural extension into payment processing, particularly since the App Store was built on the same infrastructure as iTunes.

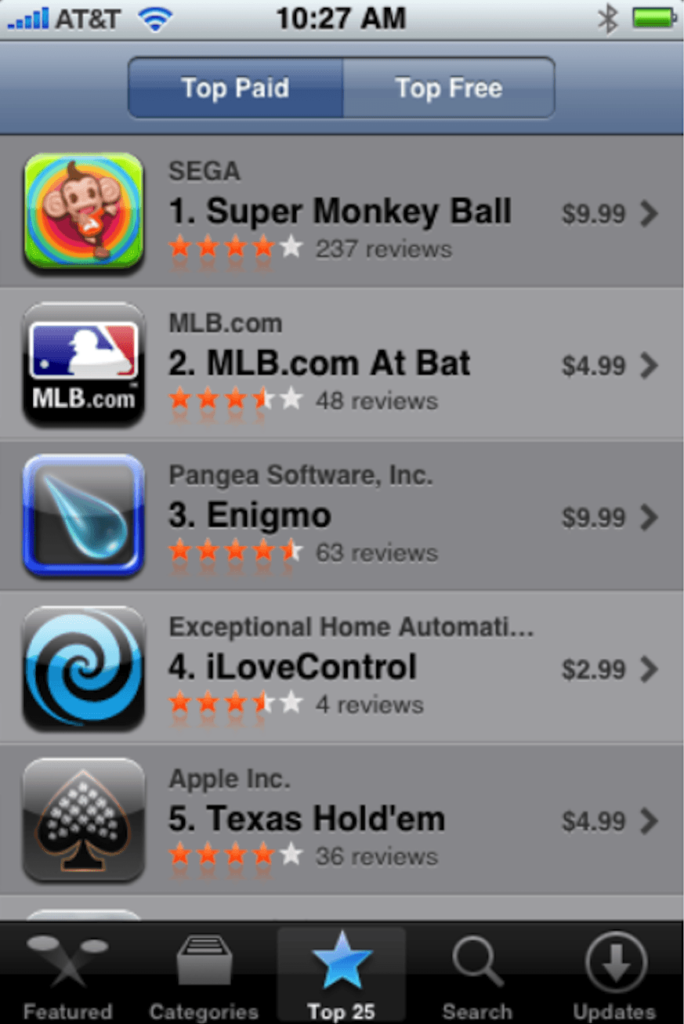

Unsurprisingly, like iTunes at the time, payment processing functionality was limited to up-front purchases. Suppose you wanted Super Monkey Ball: you had to pay $9.99 to even download the app; there were no trials or in-app purchases:

From the beginning Apple kept 30% of every purchase; that was similar to the rate the company kept for iTunes purchases, and perhaps more pertinently, just barely covered credit card processing fees for a $0.99 app.1

This gets at why this was another great deal for everyone involved: most users had already trusted Apple with their credit card information, and again, Apple was extending that trust to every developer in its App Store, making it far more likely that developers would earn money on their apps than if they had to drive downloads and purchases on their own. And once again, this circled back to Apple’s benefit, both in terms of the ecosystem broadly and, as the App Store reached scale (and added in-app purchasing), real profits.

App Store Part Three: Customer Management

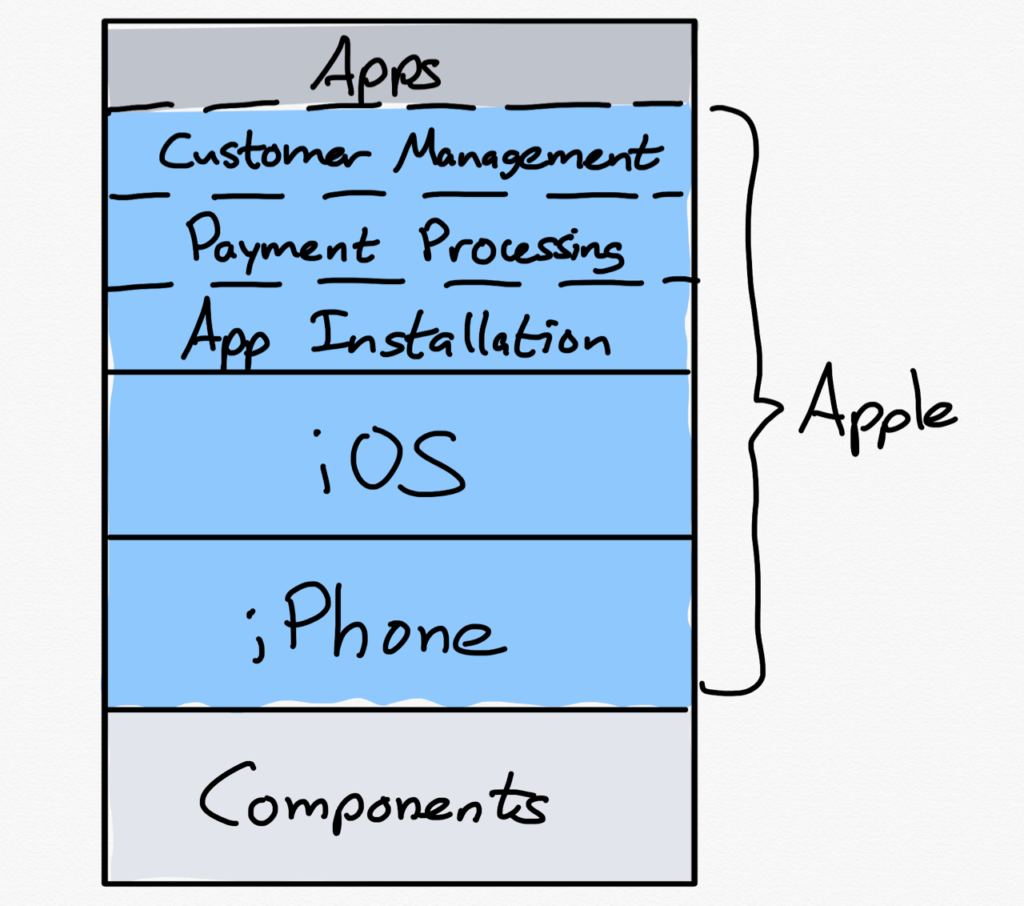

That Apple has controlled app installation and payment processing from the beginning is an obvious point; what is less appreciated is that Apple leveraged its control of payment processing, which was based on its control of app installation, which was based on its control of the operating system, into complete ownership of the customer relationship.

Users didn’t pay developers, they paid Apple, who paid developers. Users didn’t get receipts from developers, they got receipts from Apple, who kept their email address for themselves. This did have some user benefits, particularly in terms of ensuring their data was not sold to unscrupulous data brokers, but the benefit to developers was much less clear cut. There remains no means to offer refunds, for example, and for many years developers could not respond to negative reviews in the App Store.

What was most frustrating for developers, though, was that the lack of a customer relationship, in conjunction with the lack of functionality for upgrade pricing, made it difficult to build sustainable businesses in product spaces that did not have an obvious service component (which might require a subscription) or consumables (which could be bought with in-app purchases). The App Store was about transactions, not relationships, and Apple liked it that way.

These three distinct integrations, each of which built on the previous, were present in the App Store from Day One — and Steve Jobs knew it. He articulated what just took me 700 words in a crisp five minutes and seven seconds:2

Everything about this video was exceptional at the time, and just as critically, nothing was objectionable. After all, the iPhone was still a small business; from a developer perspective, the App Store was (almost) all upside. It would be users who would vote with their wallets in favor of Apple’s approach.

App Store Problems

There is a bit of a running joke in tech that the mainstream media believes that every tech company is ridiculously over-valued right up until the day that the exact same company is a juggernaut that is killing industries; in the case of Apple, the company’s strategy was doomed right up until it was illegal, or so it seems with the App Store.

In truth, though, while many of the issues surrounding the App Store are about Apple being a whole lot bigger than they were in 2008, the company has, particularly over the last few years, extended its control further and further away from the core integration that undergirds its business.

Last year, for example, the company required that apps that utilize third-party login services also utilize “Sign in with Apple” (which had to be at the top of the list). This, by extension, meant that cross-platform apps and services had to integrate “Sign in with Apple” into their Android and web apps. This was in part a further assumption of customer management, and also an extension of control beyond the iPhone.

Apple’s control of the customer relationship has also helped sustain its control of payment processing; after Amazon advertised that Kindle books were available on all platforms Apple forced the bookseller to stop selling books in its app. Moreover, Amazon couldn’t even tell users to visit Amazon.com, much less offer a link or, as Android allows, a webview of the store.

What is troubling about this example, which also applies to Netflix, Spotify, and other so-called “Reader” apps, is that Apple’s aggressive integration up the stack isn’t really helping anyone. Users are confused, these big developers get fewer customers than they might have otherwise, while Apple’s overall iPhone experience is degraded. The ones that really lose out, though, are smaller developers whose cost structures cannot support Apple’s 30% cut, yet don’t have the brand awareness to enable customers to find their websites. In this way Apple is actually making dominant companies even stronger (much like they are Facebook).

Apple also appears to be making an effort to limit this exception; while Basecamp managed to drive Apple to a face-saving retreat from its insistence on in-app purchase for its Hey email service, I heard from many developers that App Store review had started rejecting apps that had been in the store for years because they only allowed users to subscribe on the web.

What was particularly disappointing about these shakedowns, though, is that Apple itself admitted in a press release that it had been holding up bug fixes in App Review “over guideline violations”, many of which were about driving usage of its own payment processor. This is truly an inversion of the win-win-win dynamic that characterized the company’s previous integration efforts: now users were being put at risk for bugs developers were liable for because of arbitrary reasons related to Apple’s drive for Services revenue.

Of course Apple had long put users at risk in other ways; the company had turned a blind eye to the search for digital whales who would spend huge amounts of money on games they could never win. This was, in retrospect, the canary in the coal mine about the corrupting power of the App Store: Apple had started out bragging how they would protect users, but the company seemed far more concerned about protecting its bottom line.

And worst of all, while this was happening, App Store functionality, particularly around payments, was being left in the dust by companies like Stripe, Square, Shopify, and even PayPal. While these companies were making it radically easier for developers to accept payments, offer subscriptions, even get loans and manage their finances, Apple’s payment solution took years to even support subscriptions (never mind that that solution is so difficult to use that a startup just raised $15 million to provide basic tracking functionality); in-app purchase still doesn’t support traditional trials3 or upgrades, the importance of which I’ve been writing about for years.

For me this is the biggest disappointment. I have long believed that the Internet is going to fundamentally remake all aspects of society, including the economy, and that one area of immense promise is small-scale entrepreneurship. The App Store was, at least at the beginning, a wonderful example of this promise; as Jobs noted even the smallest developer could reach every iPhone on earth. Unfortunately, without even a whiff of competition, the App Store has now become a burden for most small developers, who instead of relying on the end-to-end functionality offered by, say, Stripe, have to support at least two payment solutions, the combined functionality of which is limited to the lowest common denominator, i.e. the App Store.

All that noted, what does remain valuable is Apple’s total control of the installation process. The iPhone is probably the most valuable target on earth for scams and hackers, and while vulnerabilities have been exploited, there is no denying the fact that users are safer on iOS than they are on other platforms, and that is valuable to everyone involved.

The Epic Lawsuit

All of this explains why I find Epic’s lawsuit against Apple, which was filed last Thursday after the company updated Fortnite to include an alternate payment system, and was promptly kicked out of the store by Apple, such a bummer.

Epic is attacking every level of the iPhone stack: the company doesn’t just want a direct relationship with customers, and it doesn’t just want to use its own payment processor; it is also demanding the right to run its own App Store. There is precedence on the PC: there Epic has built a rival to Steam that has benefited gamers most of all; at the same time, the PC has always been completely open, for better and for worse.

My preferred outcome would see Apple maintaining its control of app installation. I treasure and depend on the openness of PCs and Macs, but I am also relieved that the iPhone is so dependable for those less technically savvy than me. What would be a far better outcome, at least from my perspective, would be Apple remembering that those same users that benefit from the iPhone being locked down should be the focus everywhere.

That means, for example, allowing purchases via webviews, particularly for products and experiences that are not zero marginal costs. Sure, that could mean less App Store revenue in the short run, but Apple would be well-served having to build more and better products to win developers over. At the end of the day, squeezing businesses that can stomach the cost of Apple development, both in terms of implementing in-app purchase and that 30%, by definition has less ultimate upside than growing the pie for everyone.

This lawsuit is also a reminder that Apple has a lot to lose. While the most likely outcome is an Apple victory — the Supreme Court has been pretty consistent in holding that companies do not have a “duty to deal” — every decision the company makes that favors only itself, and not society generally, is an invitation to examine just how important the iPhone is to, well, everything.

Indeed, this is the most frustrating aspect of this debate: Apple consistently acts like a company peeved it is not getting its fair share, somehow ignoring the fact it is worth nearly $2 trillion precisely because the iPhone matters more than anything. This is not a console you play to entertain yourself, or even a PC for work: it is the foundation of modern life, which makes it all the more disappointing that Apple seems to care more about its short term bottom line than it does about the users and developers that used to share in its integration upside; if Apple doesn’t change course, hyperessential will at some point trump hypercompetitive.

- Credit card processing fees generally consist of a fixed fee between $0.25 and $0.30 per transaction, plus 1.5%~3.0%; Apple of course would have had a significant volume discount.

- Although I can’t help but note that 2:30 mark has a very rare Apple presentation error: the Backgammon game should be on the iPhone screen

- You can trial a subscription only

文章版权归原作者所有。