The Idea Adoption Curve

Matthew Yglesias, in his new book One Billion Americans, admits:

The One Billion Americans agenda — tripling the American population — is a radical suggestion that lies well outside the boundaries of conventional political arguments.

Ezra Klein, in his new book Why We’re Polarized, promises:

What I am trying to develop here isn’t so much an answer for the problems of American politics as a framework for understanding them. If I’ve done my job well, this book will offer a model that helps make sense of an era in American politics that can seem senseless.

Klein’s promise is very similar to the brand promise of Vox, the digital media site he co-founded with Yglesias and Melissa Bell: “Explain the news”. Yglesias, on the other hand, seems more invested in creating the news that future Vox might one day explain. I think the distinction is meaningful even with the news that both Yglesias and Klein are leaving the company they founded: in fact, I think the distinction explains their destinations.

Crossing the Chasm

In the introduction of his classic tech marketing book, Crossing the Chasm, Geoffrey A. Moore writes:

This book is unabashedly about and written specifically for marketing within high-tech enterprises. But high tech can be viewed as a microcosm of larger industrial sectors. In this context, the relationship between an early market and a mainstream market is not unlike the relationship between a fad and a trend. Marketing has long known how to exploit fads and how to develop trends. The problem, since these techniques are antithetical to each other, is that you need to decide which one—fad or trend—you are dealing with before you start. It would be much better if you could start with a fad, exploit it for all it was worth, and then turn it into a trend.

That may seem like a miracle, but that is in essence what high-tech marketing is all about. Every truly innovative high-tech product starts out as a fad—something with no known market value or purpose but with “great properties” that generate a lot of enthusiasm within an “in crowd” of early adopters. That’s the early market. Then comes a period during which the rest of the world watches to see if anything can be made of this; that is the chasm. If in fact something does come out of it—if a value proposition is discovered that can be predictably delivered to a targetable set of customers at a reasonable price—then a new mainstream market segment forms, typically with a rapidity that allows its initial leaders to become very, very successful.

The key in all this is crossing the chasm—performing the acts that allow the first shoots of that mainstream market to emerge. This is a do-or-die proposition for high-tech enterprises; hence it is logical that they be the crucible in which “chasm theory” is formed. But the principles can be generalized to other forms of marketing, so for the general reader who can bear with all the high-tech examples in this book, useful lessons may be learned.

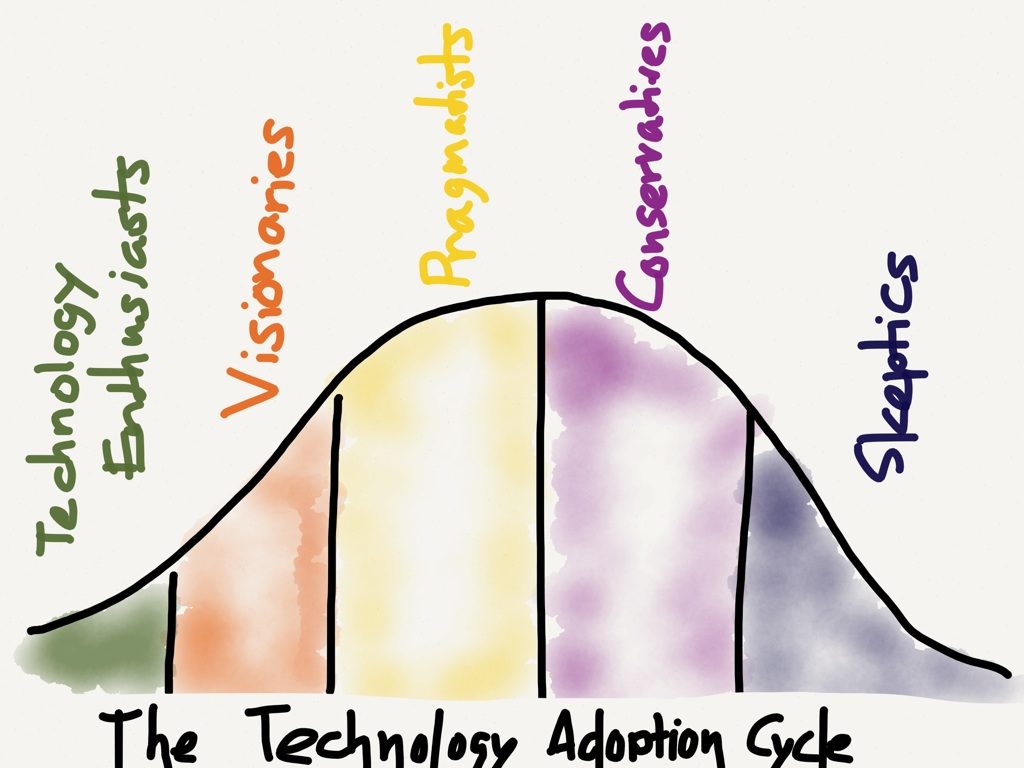

Moore divided tech markets into five parts, that I summarized in 2015’s The End of Trickle-Down Technology:

- Technology Enthusiasts love tech first and foremost, and are always looking to be on the cutting edge; they are the first to try a new product

- Visionaries love new products as well, but they also have an eye on how those new products or technologies can be applied. They are the most price-insensitive part of the market

- Pragmatists are a much larger segment of the market; they are open to new products, but they need evidence they will work and be worth the trouble, and they are much more price conscious

- Conservatives are much more hesitant to accept change; they are inherently suspicious of any new technology and often only adopt new products when doing so is the only way to keep up. Because they don’t highly value technology, they aren’t willing to pay a lot

- Skeptics are not just hesitant but actively hostile to technology

Allow me to take Moore at his word, and apply this model to something rather different than tech B2B marketing: ideas. It seems to me that Yglesias and Klein are focused on different parts of this adoption cycle. Yglesias is somewhere between an enthusiast and a visionary; the core concept of his book is closer to the former, and the policy prescriptions closer to the latter. Klein, meanwhile, is focused more on pragmatism, or even conservatism: explaining, instead of creating.

This is, to be sure, a crude simplification of two writers with nearly 40 years of material between them, but I don’t think it is an accident that Yglesias has set out on his own on Substack, whereas Klein is joining the New York Times.

The Idea Adoption Curve

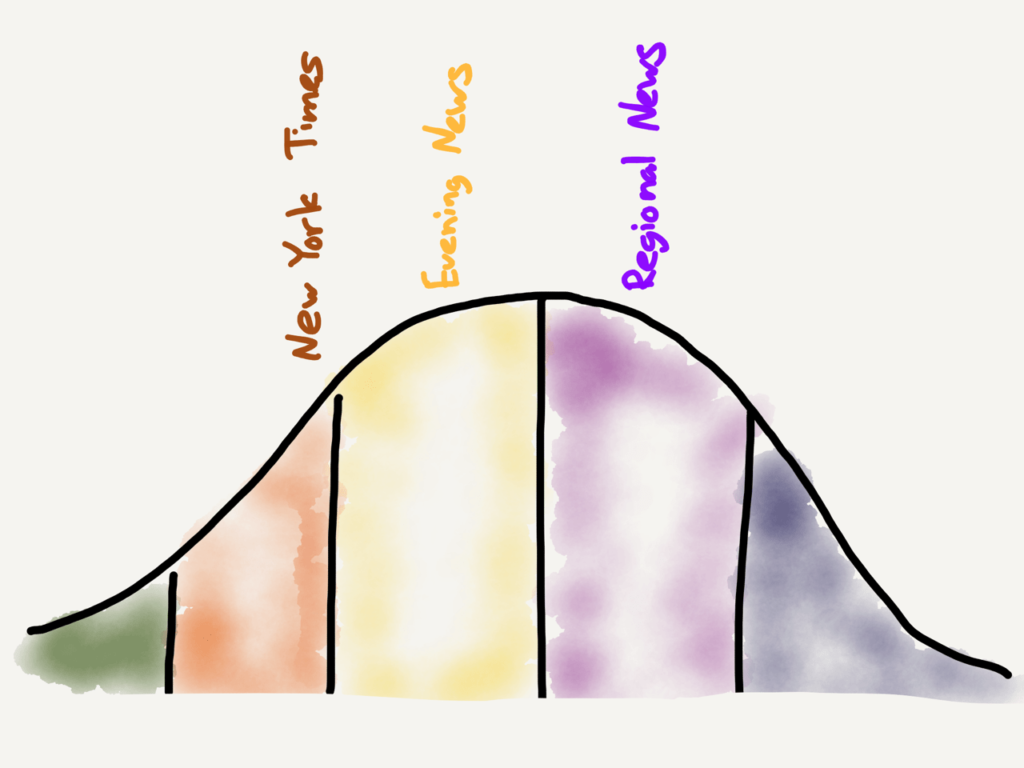

I wrote last month about the New York Times‘s traditional role in setting the national news agenda; headlines in the New York Times in the morning were lead stories on national newscasts in the evening, and headlines in regional papers the following day. If you map this dynamic to Moore’s model, it might look like this:

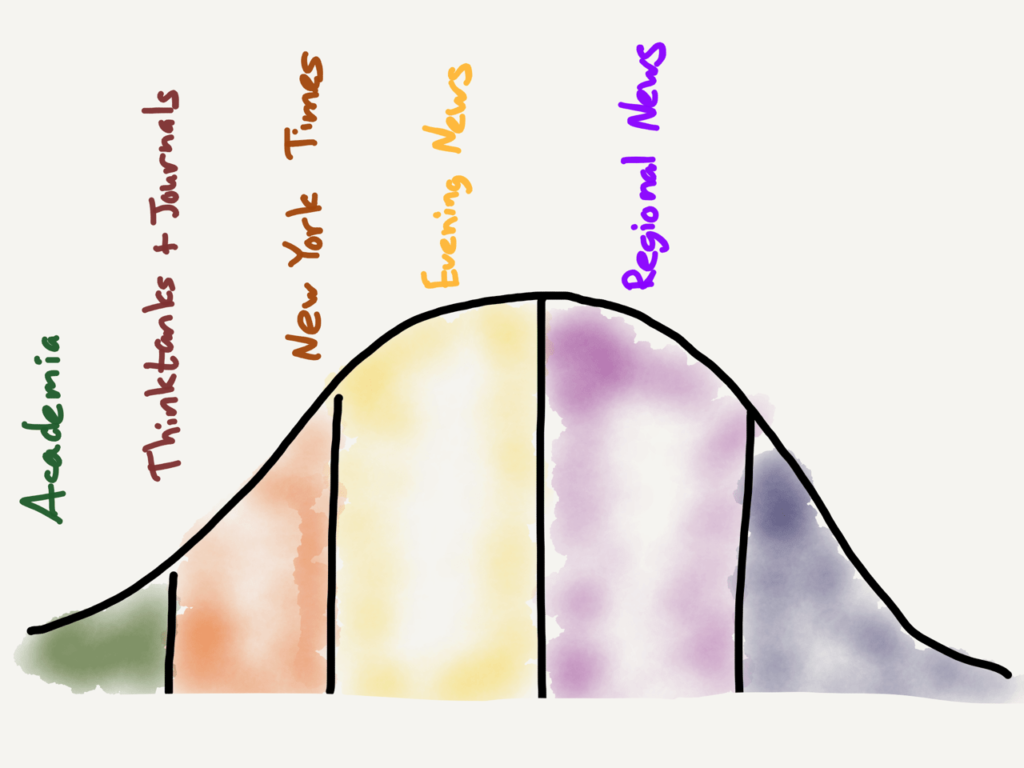

Where, though, did the New York Times get its ideas? Obviously a lot of stories came from its own reporting, or that of its peers, but the “enthusiast” part of the curve was mostly centered in academia. Visionaries, meanwhile, were a collection of think tanks, journals, and speciality magazines that operated at a loss, which was fine because making money was never the point: getting ideas into publications like the New York Times was.

What happened in the 2000s, when Yglesias and Klein first burst on the scene as part of the original generation of political bloggers, was the development of a new genre of “enthusiasts” who were creating and debating new ideas mostly for free. Sure, most of these bloggers found work with publications like American Prospect (Yglesias) or Washington Monthly (Klein), but those publications were political projects, not economic ones, with the goal of influencing the mass market, not monetizing it.

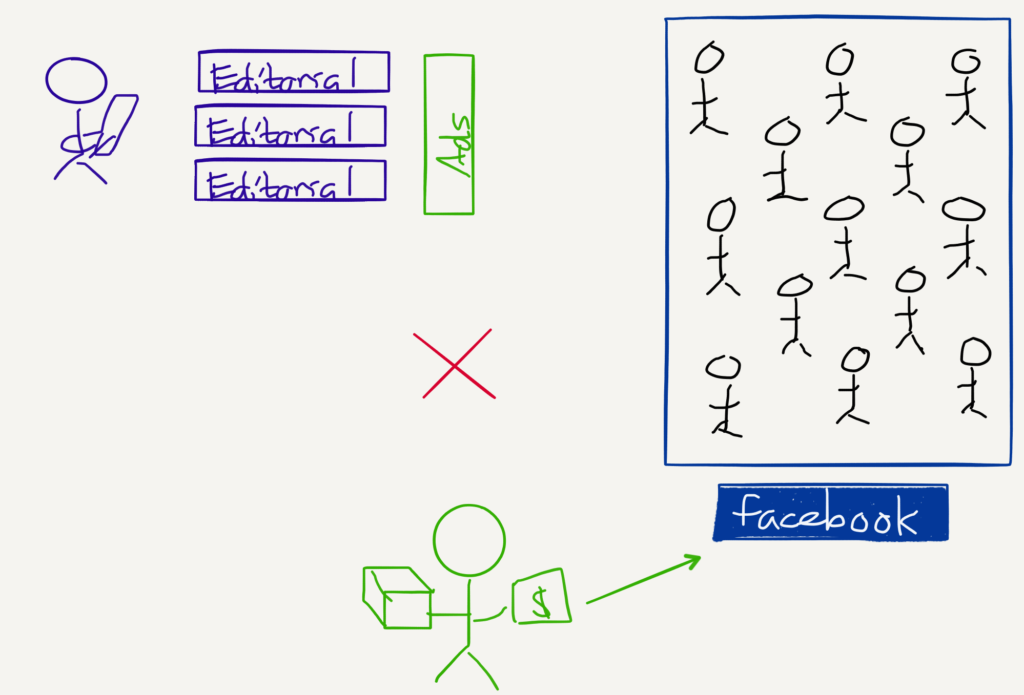

Vox, on the other hand, has been something much different, both in terms of mission statement and business model. “Explaining the news” is, from a certain perspective, about crossing the chasm on the idea curve; enthusiasts have created new ideas, and visionaries have refined them, and now the challenge is to spread those ideas to the population generally. Vox’s business model, meanwhile, is firmly on the right hand side of the curve. Advertising is all about scale, and the vast majority of the market falls to the right of the chasm.

The problem with this approach, though, is that publications simply aren’t as good at advertising as Facebook and Google. I wrote five years ago in Popping the Publishing Bubble:

Publishers and ad networks are locked in a dysfunctional relationship that doesn’t serve readers or advertisers, and it’s only a matter of time until advertisers — which again, care only about reaching potential customers, wherever they may be — desert the whole mess entirely for new, more efficient and effective advertising options that put them directly in front of the people they care about. That, first and foremost, is Facebook, but other social networks like Twitter, Snapchat, Instagram, Pinterest, and others will benefit as well:

I don’t know the specifics of how Vox’s business is doing, although it is notable that the site’s previous ad inventory is now mostly filled with requests for donations; meanwhile, there is no confusion about the business models of either Substack or the New York Times.

Visionaries and Substack

Start with Yglesias, and Substack; this is obvious a business model near-and-dear to my heart, given that Stratechery was perhaps the first site built around the idea of a one-person publication supported by subscriptions at scale.1 I don’t have any illusions about reaching the mass market; Stratechery is very much predicated on capturing the “Visionary” part of the curve. Read again the explanation I excerpted above:

Visionaries love new products as well, but they also have an eye on how those new products or technologies can be applied. They are the most price-insensitive part of the market

The “price-insensitive” part is key: Stratechery and Substack publications like Slow Boring may not be that expensive, but they are, relative to text on the Internet, shockingly pricey. Subscribers, though, don’t mind, as long as what they are getting is consistently unique and provocative; look no further than One Billion Americans, or Yglesias’s Twitter account, to see why he ended up on Substack.

What is neat about this model is that it is far more sustainable and accessible than the old model of corporations and donors subsidizing think tanks, journals, and specialty magazines, and far more ideologically diverse than academia. It is important, though, to be honest about the model’s limitations: while I remain very bullish about the potential of subscription-based local news entities, it is difficult to envision a future where most people pay for news or analysis directly.

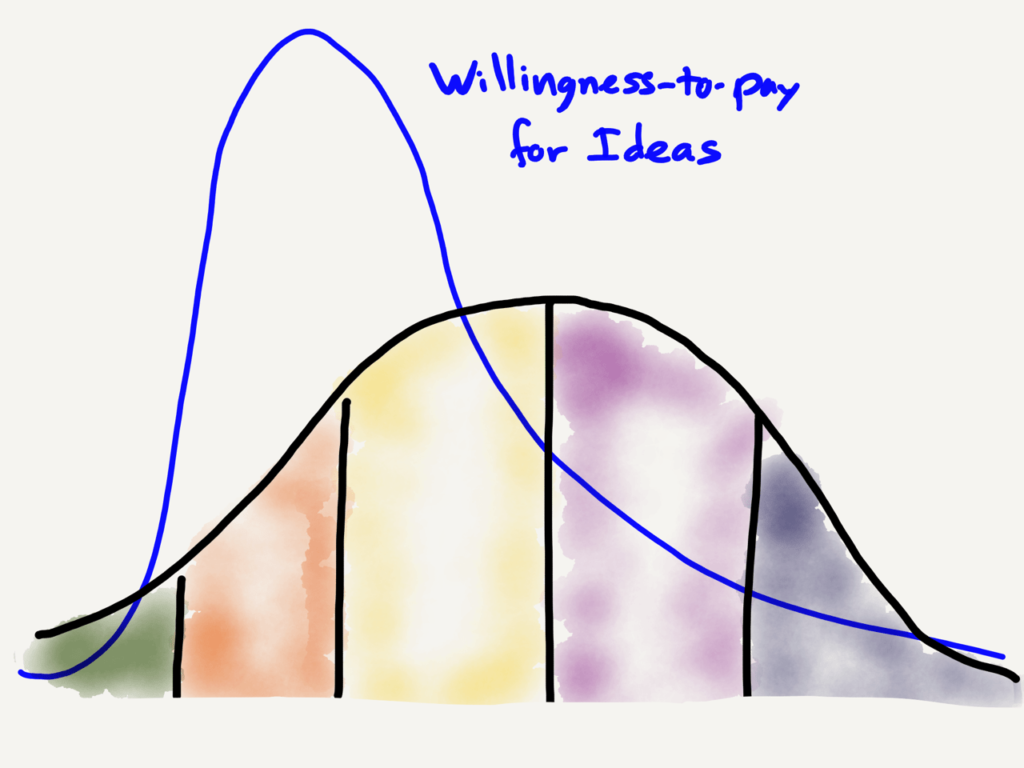

One way to understand why is to map the Idea Adoption Curve against a “Willingness-to-Pay Curve”; I suspect it looks something like this:

Enthusiasts — now on Twitter, for the most part — generate and debate ideas for free, while the real money, at least from an average revenue per user perspective, is with the visionaries. This is where the Substack model makes the most sense. What is notable, though, is that the chasm of ideas is also a chasm of monetization.

Push Versus Pull

How do ideas cross the chasm into popular acceptance and public policy? Vox tried to pull them over, with, I think, limited success; the New York Times, on the other hand, has been positioned to cross the chasm for decades. What has changed is that while the New York Times used to be mostly supported by advertising, which incentivized it to remain planted on the right side of the divide, pulling ideas from the fringes into the mainstream, its shift to subscriptions has pushed it to the left part of the curve, incentivizing the newspaper of record to more actively generate and push new ideas.

This has, as I noted in Never-Ending Niches, changed the New York Times:

To the extent that the New York Times has been successful online — and the company has been very successful indeed! — it follows that the company is well-placed in terms of both focus and quality, and in that order.

In this view, the fact that deeply reported articles about Chinese disinformation on Twitter are held as being low quality by the Chinese government is immaterial; what matters is that the New York Times‘ audience, which is mostly in the United States, finds it of high quality (I certainly do).

That’s an easy example, but there are ones that hit closer to home; for example, I thought this 2018 story that claimed that Facebook Gave Data Access to Chinese Firm Flagged by U.S. Intelligence was, as I wrote at the time, “deeply flawed at best, and willfully mendacious at worst.” It turns out, though, that I am not particularly interested in the “Everything tech does is bad” niche; that story was very high quality for much of the New York Times’s audience.

These two stories were in the News section, not Opinion, but the point is that the distinction matters less than ever before; the pursuit of subscription revenue pushes the New York Times to the left side of the chasm, which means that to the extent it still fulfills it role of conveying ideas across the chasm it is more focused on pushing particular points of view into the broader public, as opposed to pulling ideas the broader public may favor. This certainly makes the New York Times an attractive landing place for Klein, who, for all of his focus on “explaining the news”, has never been shy about his political preferences and desire to influence policy. Now he can do so from a platform that has long been defined by its ability to cross the chasm.

BuzzFeed Versus the New York Times

Yglesias and Klein’s departures from Vox weren’t the only media news of the week; BuzzFeed acquired HuffPost (and some cash from Verizon). In an interview on Recode Media, BuzzFeed CEO and founder — of both BuzzFeed and HuffPost! — Jonah Peretti took aim at the New York Times’ shift; from Recode:

The Times, Peretti allowed, has since refined a very good subscription business model, which has allowed it to make better journalism by hiring more and better talent. This is not a controversial opinion. But the next part may be: The New York Times, Peretti argued, can’t really be called “the paper of record” anymore — because of that same subscription model.

“A subscription business model leads towards being a paper for a particular group and a particular audience and not for the broadest public,” Peretti said. He’s alluding, in part, to the theory that the Times’s subscriber base wants to read a certain kind of news and opinion — middle/left of center, critical of Donald Trump, etc. — and that straying from that can cost it subscribers. But he’s also simply arguing that the act of requiring readers to pay to read cuts the Times off from a big audience.

Peretti’s solution to that problem, it turns out, sounds a whole lot like a combined BuzzFeed/HuffPost — publications that are widely distributed, supported by advertising, and free:

“Will a subscription newspaper that is read by a subset of society have as big an impact as it could on voters, on the broad public, on young people, on the more diverse rising generation of millennials and Gen Z?” he argued. “I think there’s a huge opportunity to serve those consumers. And not all of them are going to be subscribers to any publication.”

BuzzFeed is firmly planted on the right side of the Idea Adoption Curve; most of the publication’s content is about anything other than news or ideas, and its primary distribution network is Facebook (Twitter is for the left side of the curve, and Facebook the right). It also has a n advertising

kitchen sink business model, with a combination of premium advertising, programmatic advertising, affiliate marketing, e-commerce, etc., all of which only make sense at scale.

The Implications of Abundance

At the same time, it is worth noting that the New York Times has, contrary to Peretti’s implication, never been a newspaper for the masses. Sure, its subscription model is by default exclusionary, but only being available in printed form, mostly in New York, was far more exclusionary. The point about subscriptions driving a particular point of view is a valid one, but then again, it is not as if BuzzFeed has been shy about its political preferences either. The reality is that the implication of the Internet is that ideas are in abundance, and people will seek out what they already agree with, as opposed to accepting what is delivered to them.

This explains the newly prominent role of the right side of the Idea Adoption Curve; I noted while summarizing the Technology Adoption Curve:

Skeptics are not just hesitant but actively hostile to technology

This, translated to ideas, explains the prominence of conspiracy theories and misinformation. These strains of belief have always existed, in America in particular, but one implication of the Internet leveling the information playing field is that these alternative views of reality can both spread further than ever before, even as they are far more visible to everyone else. This is both reason for alarm, and for skepticism about said alarm: yes, the misinformation problem is worse than before, but much of our fear is rooted in newfound awareness of an old problem, and there is a strong case to be made that the emergence of valuable information makes up for the propagation of misinformation that mostly feeds confirmation biases.

What is indisputable, though, is that the nature of information and its spread has been fundamentally altered in a way unseen since the printing press. It affects Yglesias and Substack, Klein and the New York Times, and, one increasingly suspects, the very fabric of society and the foundation of our political institutions and organizing principles. And, if this is right, we are only now at the end of the beginning.

- Yes, subscription-based newsletters existed long before Stratechery, particularly on Wall Street, but at much higher price points

文章版权归原作者所有。