New Defaults

New Defaults ——

One of the most well-known papers in behavioral economics is The Power of Suggestion: Inertia in 401(k) Participation and Savings Behavior by Brigitte C. Madrian and Dennis F. Shea. From the introduction:

In this paper we analyze the 401(k) savings behavior of employees in a large U. S. corporation before and after an interesting change in the company 401(k) plan. Before the plan change, employees who enrolled in the 401(k) plan were required to affirmatively elect participation. After the plan change, employees were automatically enrolled in the 401(k) plan immediately upon hire unless they made a negative election to opt out of the plan. Although none of the economic features of the plan changed, this switch to automatic and immediate enrollment dramatically changed the savings behavior of employees.

I would certainly call a shift from 37 percent participation to 86 percent participation a dramatic shift! However, as Madrian and Shea note, there was a downside:

For the NEW cohort, 80 percent of 401(k) contributions are allocated to the money market fund, while only 16 percent of contributions go into stock funds. In contrast, the other cohorts allocate roughly 70 percent of their 401(k) contributions to stock funds, with less than 10 percent earmarked for the money market fund

The issue is that the money market fund was the default choice, which meant that while the new program helped people save more, it also led folks who would have chosen better-performing funds to earn far less than they would have. Defaults are powerful!

Just ask Facebook, which is conducting a (probably futile) public relations campaign against Apple over iOS 14’s impending “App Tracking Transparency” requirement. Apple told Bloomberg:

Apple defended its iOS updates, saying it was “standing up” for people who use its devices. “Users should know when their data is being collected and shared across other apps and websites — and they should have the choice to allow that or not,” an Apple spokeswoman said in a statement. “App Tracking Transparency in iOS 14 does not require Facebook to change its approach to tracking users and creating targeted advertising, it simply requires they give users a choice.”

In fact, users have had a choice for several years; Apple has given customers the ability to switch off their device’s “Identifier for Advertisers” (IDFA) since 2012. What makes iOS 14 different is the change in defaults: instead of users needing to turn IDFA off, every app has to explicitly ask for it to be turned on, and given the arguably misleading way that this tracking is presented by the media generally and Apple specifically, both Facebook and Apple expect customers to say no; indeed, Facebook won’t even bother asking. Changing the defaults can change the course of a multi-billion dollar company.

China, Control, and Quarantine

One year ago, on January 5, 2020, Wuhan, Hubei province’s largest city, was set to host the 3rd Session of the 13th Hubei Provincial People’s Congress and the 3rd Session of the 12th Hubei Provincial Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, the two most important political gatherings of the year. Perhaps that is why the city reported no new cases of a mysterious respiratory illness that had started appearing the previous November for the following 11 days. Three weeks later, the entire city was locked down in a drastic attempt to contain the virus we now know as SARS-CoV-2.

Last week, meanwhile, came a lockdown of another sort; from the New York Times:

A Chinese court on Monday sentenced a citizen journalist who documented the early days of the coronavirus outbreak to four years in prison, sending a stark warning to those challenging the government’s official narrative of the pandemic. Zhang Zhan, the 37-year-old citizen journalist, was the first known person to face trial for chronicling China’s outbreak. Ms. Zhang, a former lawyer, had traveled to Wuhan from her home in Shanghai in February, at the height of China’s outbreak, to see the toll from the virus in the city where it first emerged. For several months she shared videos that showed crowded hospitals and residents worrying about their incomes…

Ms. Zhang’s trial, at the Shanghai Pudong New District People’s Court on Monday, lasted less than three hours. The official charge on which she was convicted was “picking quarrels and provoking trouble,” a vague charge commonly used against critics of the government. Prosecutors had initially recommended a sentence between four and five years.

For all of the consternation in China about the the initial cover-up, Zhang’s case is a reminder that controlling information for political purposes is China’s default approach. It is worth noting, though, that the willingness to exert control can be useful, particularly during a pandemic. While Wuhan’s lockdown drew the most attention, and some degree of emulation, that wasn’t what actually stopped the virus’ spread. The Wall Street Journal explained in March:

The cordon sanitaire that began around Wuhan and two nearby cities on Jan. 23 helped slow the virus’s transmission to other parts of China, but didn’t really stop it in Wuhan itself, these experts say. Instead, the virus kept spreading among family members in homes, in large part because hospitals were too overwhelmed to handle all the patients, according to doctors and patients there.

What really turned the tide in Wuhan was a shift after Feb. 2 to a more aggressive and systematic quarantine regime whereby suspected or mild cases — and even healthy close contacts of confirmed cases — were sent to makeshift hospitals and temporary quarantine centers. The tactics required turning hundreds of hotels, schools and other places into quarantine centers, as well as building two new hospitals and creating 14 temporary ones in public buildings.

These centralized quarantines were not optional, and they were effective: China had the coronavirus largely under control by late spring, and the economy has unsurprisingly bounced back; China is expected to be the only Group of 20 country to record positive growth for the year.

The West’s Haphazard Approach

The United States (along with Europe, it should be noted), has not done so well. Actually, that’s being generous: by pursuing selective lockdowns and completely eschewing centralized quarantine, the West has managed to hurt its economies and kill its small businesses, without actually stopping the spread of the coronavirus. At the same time, as Tyler Cowen argued in Bloomberg last May, centralized quarantines were never really a serious option:

There has been surprisingly little debate in America about one strategy often cited as crucial for preventing and controlling the spread of Covid-19: coercive isolation and quarantine, even for mild cases. China, Singapore and South Korea separate people from their families if they test positive, typically sending them to dorms, makeshift hospitals or hotels. Vietnam and Hong Kong have gone further, sometimes isolating the close contacts of patients.

I am here to tell you that those practices are wrong, at least for the U.S. They are a form of detainment without due process, contrary to the spirit of the Constitution and, more important, to American notions of individual rights. Yes, those who test positive should have greater options for self-isolation than they currently do. But if a family wishes to stick together and care for each other, it is not the province of the government to tell them otherwise.

Cowen’s first paragraph makes clear that the views in the second are widely held: no politician that I know of, in the U.S. or Europe, seriously argued for centralized quarantine, even though it was likely the only way to contain SARS-CoV-2. The very idea of governments locking up innocent civilians is counter to our default assumption that individual freedom is inviolate.

That, though, is why it is strange that so many have acquiesced to ever-tightening restrictions on information. It seems that over the last year to have a pro-free speech position has become the exception; the default is to push for censorship, if not by the government — thanks to that pesky First Amendment — then instead by private corporations. And meanwhile, said private corporations, eager to protect their money-making monopolies (in the political sense if not the legal one), are happy to comply; YouTube led the way, declaring in April that it would ban any coronavirus content that contradicted the same World Health Organization that tweeted on January 14th that there was no human-to-human transmission, but most tech companies have since fallen in line.

To be perfectly clear, I am in no way denying the presence of huge amounts of misinformation, which, by the way, continue to circulate widely despite tech companies’ best efforts. What concerns me is that this sort of dime store authoritarianism is resulting in the worst possible outcome:

China’s control of information is not ideal — the Wuhan coverup is about as compelling an example as you will ever see of the downsides of information control — but at the same time, it would be dishonest to not recognize that authoritarianism can be effective in actually controlling a pandemic. The West, though, will neither do what it takes to contain the coronavirus, even as we flirt with information suppression at scale. What makes this nefarious is that the cost of the latter is often unseen — it is the ideas never broached, and the risks never taken. But how do you measure opportunity cost?

Vaccines and Defaults

Here the coronavirus again provides a compelling example, this time in the form of Moderna’s RNA vaccines. David Wallace-Wells wrote in New York Magazine in December:

You may be surprised to learn that of the trio of long-awaited coronavirus vaccines, the most promising, Moderna’s mRNA-1273, which reported a 94.5 percent efficacy rate on November 16, had been designed by January 13. This was just two days after the genetic sequence had been made public in an act of scientific and humanitarian generosity that resulted in China’s Yong-Zhen Zhang’s being temporarily forced out of his lab. In Massachusetts, the Moderna vaccine design took all of one weekend. It was completed before China had even acknowledged that the disease could be transmitted from human to human, more than a week before the first confirmed coronavirus case in the United States. By the time the first American death was announced a month later, the vaccine had already been manufactured and shipped to the National Institutes of Health for the beginning of its Phase I clinical trial. This is — as the country and the world are rightly celebrating — the fastest timeline of development in the history of vaccines. It also means that for the entire span of the pandemic in this country, which has already killed more than 250,000 Americans, we had the tools we needed to prevent it.

As Wallace-Wells notes, this does not mean that the Moderna vaccine should have — or could have — been rolled out in January. It does, though, provide a powerful thought experiment about opportunity cost.

Opportunity cost is distinct from the costs normally calculated in a cost-benefit analysis: those costs are real costs, in that they are actually incurred. For example, if I want to buy a new sweater, it will cost me money. Opportunity cost, on the other hand, is the choice not made. To return to the sweater example, whatever funds I use to buy a sweater cannot be used to buy slacks — the slacks are the opportunity cost.

In the case of the vaccine, the opportunity costs of not deploying it the moment it was developed are enormous: hundreds of thousands of lives saved in the U.S. alone, millions around the world, and untold economic destruction avoided. Again, to be clear, I’m not saying this choice was available to us, and you can easily concoct another thought experiment where the vaccine goes horribly wrong. What makes this thought experiment worthwhile, though, is that it is such a powerful example of opportunity costs, and it is opportunity costs — the thing not learned — that are the biggest casualty of defaulting towards information control instead of free speech.

This isn’t the only mistaken default. Another topic that received minimal discussion was the concept of human challenge trials, where individuals could volunteer — and be richly compensated — to be exposed to the virus to more quickly test the vaccination’s efficacy. When I broached the idea on Twitter, plenty of folks were quick to cite the very real ethical concerns with the concept, but few seemed willing to acknowledge the opportunity costs incurred by waiting a single day longer than necessary, which ought to present ethical concerns of their own. There was also no discussion of making the vaccine broadly available in conjunction with Phase III trials, despite the fact that RNA-based vaccines are inherently safer than traditional vaccines based on weakened or inactivated viruses. Similarly, when I expressed bafflement that people weren’t outraged by the FDA’s delay in approving the vaccines, the response of many was to insist the agency was rightly prioritizing safety. What, though, about the safety of those suffering from a pandemic that was accelerating? At every step the default was a bias towards the status quo of no vaccine, no matter how great the opportunity cost may have been.

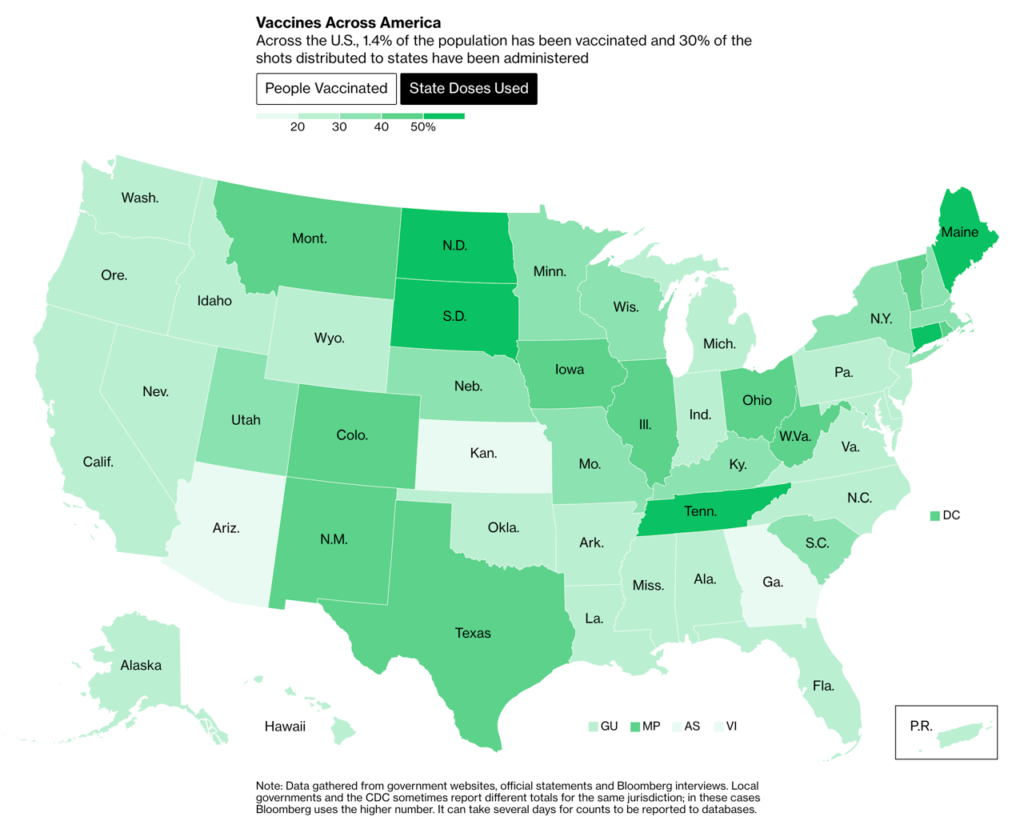

What is most dispiriting, though, is this chart from Bloomberg:

As of this morning only 30% of distributed vaccines have been administered; that’s not quite as bad as it seems given the U.S. policy to hold back the second shot in reserve (itself a conservative decision that seems driven by the status quo default), but that still means millions of shots are unused and risk expiration. A major hold-up has been strict prioritization protocols, which prioritize equitable distribution over speed. It’s another misplaced default.

Technology and Opportunity

At this point many of you are surly muttering that this was the fastest vaccine development program in history, and that the U.S., for all of its struggles, has already vaccinated 1.42% of its population, the 3rd most in the world. Both are true, and worth celebrating.

At the same time, the timeline in that New York Magazine article is worth keeping in mind: the single most important reason these vaccines were developed so quickly was because of technological progress. This brilliant article explains how mRNA vaccinations work in computer programming terms, but the entire concept is built on years of work. The Harvard Health Blog noted:

Like every breakthrough, the science behind the mRNA vaccine builds on many previous breakthroughs, including:

- Understanding the structure of DNA and mRNA, and how they work to produce a protein.

- Inventing technology to determine the genetic sequence of a virus.

- Inventing technology to build an mRNA that would make a particular protein.

- Overcoming all of the obstacles that could keep mRNA injected into the muscle of a person’s arm from finding its way to immune system cells deep within the body, and coaxing those cells to make the critical protein.

- Information technology to transmit knowledge around the world at light-speed.

Every one of these past discoveries depended on the willingness of scientists to persist in pursuing their longshot dreams — often despite enormous skepticism and even ridicule — and the willingness of society to invest in their research.

Longshot dreams, enormous skepticism, and even ridicule certainly sound familiar to anyone associated with Silicon Valley, and there is an analogy to be made between how technology accelerated vaccine development, even in the face of conservative defaults, and how the technology industry broadly has driven U.S. economic growth for decades now, even in the face of stagnation elsewhere.

What makes software so compelling to anyone ambitious is that (1) the potential applications are limitless and (2) the limitations on creation are your own imagination, not external regulations. This certainly has its downsides, as anyone trying to get a software release out the door understands; you can add new features and fix bugs forever, because after all, it’s just software. At the same time, you can build anything you want, without asking for permission, and what could be more exciting than that?

I’m reminded of this old Steve Jobs interview:

Jobs was talking about life in general, but the potential he articulates is much more easily grasped in software; what is notable is that it was the software-driven companies that performed the best throughout the pandemic. Perhaps the assumption that any problem is solvable is a muscle that can be developed in software and applied to the real world? Amazon is a striking example in this regard: the so-called “tech” company hired over 400,000 new people in 2020, as it brought its massive logistics network to bear in the face of overwhelming demand; no wonder many have been joking on Twitter that the company should be in charge of the vaccination rollout.

Or, better yet, we ought to figure out how to export the Amazon mindset beyond the world of technology, but to do that we need new defaults.

New Defaults

Start with these three:

- First, it should be the default that free speech is a good thing, that more information is better than less information, and that the solution to misinformation is improving our ability to tell the difference, not futilely trying to be China-lite without any of the upside.

- Second, it should be the default that the status quo is a bad thing; instead of justifying why something should be done, the burden of proof should rest on those who believe things should remain the same. This sounds radical, but given the fact that the world is undergoing profound changes driven by the Internet, it is the attempt to preserve the unsustainable that is radical.

- Third, it should be the default to move fast, and value experimentation over perfection. The other opportunity cost of decisions not made is lessons not learned; given the speed with which information is disseminated, this cost is higher than ever.

The urgency of this reset should come from where all of this started: China. Dan Wang wrote in his 2020 letter:

This year made me believe that China is the country with the most can-do spirit in the world. Every segment of society mobilized to contain the pandemic. One manufacturer expressed astonishment to me at how slowly western counterparts moved. US companies had to ask whether making masks aligned with the company’s core competence. Chinese companies simply decided that making money is their core competence, and therefore they should be making masks. The State Council reported that between March and May, China exported 70 billion masks and nearly 100,000 ventilators. Some of these masks had problems early on, but the manufacturers learned and fixed them or were culled by regulatory action, and China’s exports were able to grow when no one else could restart production. Soon enough, exports of masks were big enough to be seen in the export data.

This, to be clear, was not the result of authoritarianism, but despite it; Taiwan exhibited the exact same sort can-do attitude alongside a free press, elections, and pig intestines in the legislature. China, meanwhile, is increasing control of the private sector; the latest example is Alibaba and Jack Ma, who was last seen in October criticizing the country’s regulators; China proceeded to kill Ant Group’s IPO, in a signal to any other billionaires with big ideas about who was boss, and Ma’s whereabouts are unknown. The U.S. can absolutely compete with this approach, not by imitating it, but by doing the exact opposite.

Intentions Versus Outcomes

A few years after Madrian and Shea’s landmark study, Richard Thaler, the Nobel-prize winning economist at the University of Chicago, devised a new approach for 401(k) enrollments that sought to overcome the downside of default choices (while preserving their upside). What I wanted to highlight, though, was this bit from the introduction of Save More Tomorrow: Using Behavioral Economics to Increase Employee Saving:

Economic theory generally assumes that people solve important problems as economists would. The life cycle theory of saving is a good example. Households are assumed to want to smooth consumption over the life cycle and are expected to solve the relevant optimization problem in each period before deciding how much to consume and how much to save. Actual household behavior might differ from this optimal plan for at least two reasons. First, the problem is a hard one, even for an economist, so households might fail to compute the correct savings rate. Second, even if the correct savings rate were known, households might lack the self-control to reduce current consumption in favor of future consumption…

For whatever reason, some employees at firms that offer only defined-contribution plans contribute little or nothing to the plan. In this paper, we take seriously the possibility that some of these low-saving workers are making a mistake. By calling their low-saving behavior a mistake, we mean that they might characterize the action the same way, just as someone who is 100 pounds overweight might agree that he or she weighs too much. We then use principles from psychology and behavioral economics to devise a program to help people save more.

I suspect a similar story can be told about our slide to defaulting that free speech is bad, that the status quo should be the priority, and that perfect is preferable to good. These are mistakes, even as they are understandable. After all, misinformation is a bad thing, change is uncertain, and no one wants to be the one that screwed up. Everyone has good intentions; the mistake is in valuing intentions over outcomes.

To that end, the point of this article was not really to discuss the coronavirus or vaccinations: with regards to the latter, there is more to praise than to criticize, and I freely admit I am not an expert about either. And yet, that isn’t a reason to settle, or to not examine our defaults: why can’t we accomplish other big projects in a year? What else can we build with so much broad benefit so quickly? And critically, what can we change about our psychology and behavior to make that happen? New defaults are the best place to start.

文章版权归原作者所有。