Mistakes and Memes

Paul Krugman, back in 1998, was pretty sure he had this Internet thing figured out:

The growth of the Internet will slow drastically, as the flaw in “Metcalfe’s law” — which states that the number of potential connections in a network is proportional to the square of the number of participants — becomes apparent: most people have nothing to say to each other! By 2005 or so, it will become clear that the Internet’s impact on the economy has been no greater than the fax machine’s.

It is obviously easy to dunk on this statement, but back in 2015, I came, ever so slightly, to Krugman’s defense; my argument was that the reason he was wrong was not because he overrated user-generated content, but rather because he underrated the effectiveness of Aggregators giving people what they wanted:1

Still, this outcome depends on Facebook driving ever-more engagement, and I’m not convinced that more “content posted by the friends [I] care about” is the best path to success. Everyone loves to mock Paul Krugman’s 1998 contention about the limited economic impact of the Internet…[but] it’s worth considering…just how much users value what their friends have to say versus what professional media organizations produce.

Again, as I noted above, Facebook made the 2013 decision to increase the value of newsworthy links for a reason, and in the time since, BuzzFeed in particular has proven that there is a consistent and repeatable way to not only reach a large number of people but to compel them to share content as well. Was Krugman wrong because he didn’t appreciate the relative worth people put on what folks in their network wanted to say, or because he didn’t appreciate that people in their network may not have much to say but a wealth of information to share?

I was definitely more right than Krugman — easy to say about an article written in 2015 versus 1998, of course — but the truth is that I too missed the boat, both narrowly in the case of Facebook, and broadly in the case of the Internet.

Mistake One: Focusing on Demand

In that article where I quoted Krugman I added:

I suspect that Zuckerberg for one subscribes to the first idea: that people find what others say inherently valuable, and that it is the access to that information that makes Facebook indispensable. Conveniently, this fits with his mission for the company. For my part, though, I’m not so sure. It’s just as possible that Facebook is compelling for the content it surfaces, regardless of who surfaces it. And, if the latter is the case, then Facebook’s engagement moat is less its network effects than it is that for almost a billion users Facebook is their most essential digital habit: their door to the Internet.

That phrase, “Facebook is compelling for the content it surfaces, regardless of who surfaces it”, is oh-so-close to describing TikTok; the error is that the latter is compelling for the content it surfaces, regardless of who creates it. I noted in a Daily Update last year:

What I got right [in that 2015 Article] is that your social network doesn’t generate enough compelling content, but, like Facebook, I assumed that the alternative was professional content makers. The key to TikTok, as I explained yesterday, is that it is not a social network at all; the better analogy is YouTube, and if you think of TikTok as being a mobile-first YouTube, the strategic opening is obvious.

To put it another way, I was too focused on demand — the key to Aggregation Theory — and didn’t think deeply enough about the evolution of supply. User-generated content didn’t have to be simply picture of pets and political rants from people in one’s network; it could be the foundation of a new kind of network, where the payoff from Metcalfe’s Law is not the number of connections available to any one node, but rather the number of inputs into a customized feed.2

Mistake Two: Misunderstanding Supply

The second mistake is much more fundamental, because it touches on what makes the Internet so profound. From The Internet and the Third Estate:

What makes the Internet different from the printing press? Usually when I have written about this topic I have focused on marginal costs: books and newspapers may have been a lot cheaper to produce than handwritten manuscripts, but they are still not-zero. What is published on the Internet, meanwhile, can reach anyone anywhere, drastically increasing supply and placing a premium on discovery; this shifted economic power from publications to Aggregators.

Just as important, though, particularly in terms of the impact on society, is the drastic reduction in fixed costs. Not only can existing publishers reach anyone, anyone can become a publisher. Moreover, they don’t even need a publication: social media gives everyone the means to broadcast to the entire world. Read again Zuckerberg’s description of the Fifth Estate:

People having the power to express themselves at scale is a new kind of force in the world — a Fifth Estate alongside the other power structures of society. People no longer have to rely on traditional gatekeepers in politics or media to make their voices heard, and that has important consequences.

It is difficult to overstate how much of an understatement that is. I just recounted how the printing press effectively overthrew the First Estate, leading to the establishment of nation-states and the creation and empowerment of a new nobility. The implication of overthrowing the Second Estate, via the empowerment of commoners, is almost too radical to imagine.

Who, for example, imagined this?

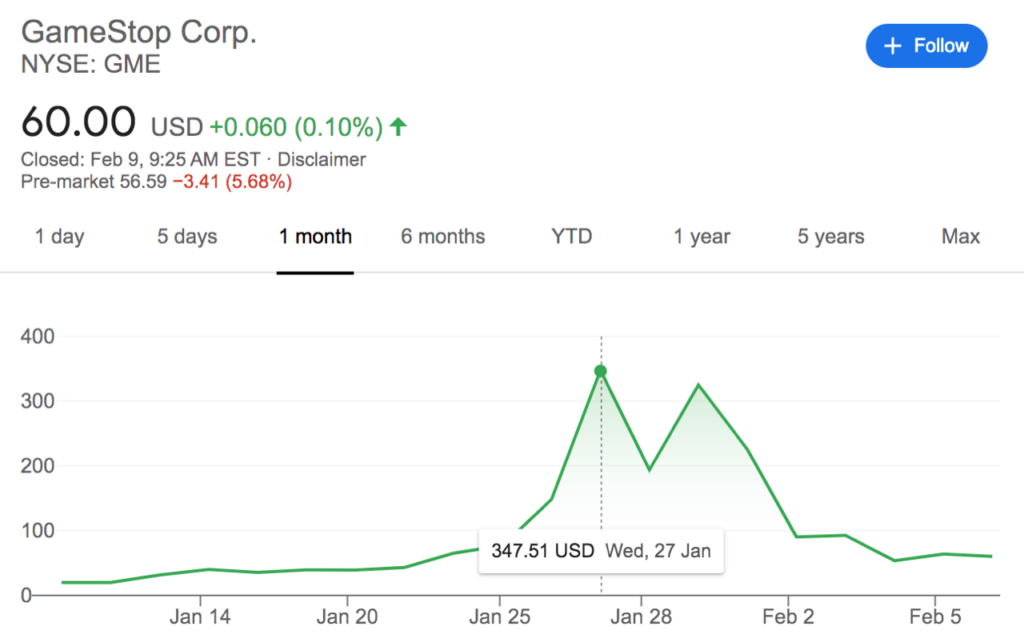

There have been a thousand stories about what the GameStop saga has been about: a genuine belief in GameStop, a planned-out short squeeze, populist anger against Wall Street, boredom and quarantine, greed, hedge fund pile-ons, you name it there is an article arguing it. I suspect that most everyone is right, much as the proverbial blind men feeling an elephant are all accurate in their descriptions, even though they are completely different. What seems clear is that the elephant is the Internet.

This is hardly a profound observation. It has been clear for many years that the Internet made it possible for new communities to form, sometimes with astonishing speed. The problem, as Zeynep Tufekci explained in Twitter and Tear Gas, is that the ease of network formation made these communities more fragile, particularly in the face of determined opposition:

The ability to use digital tools to rapidly amass large numbers of protesters with a common goal empowers movements. Once this large group is formed, however, it struggles because it has sidestepped some of the traditional tasks of organizing. Besides taking care of tasks, the drudgery of traditional organizing helps create collective decision-making capabilities, sometimes through formal and informal leadership structures, and builds a collective capacities among movement participants through shared experience and tribulation. The expressive, often humorous style of networked protests attracts many participants and thrives both online and offline, but movements falter in the long term unless they create the capacity to navigate the inevitable challenges.

Tufekci contrasts many modern protest movements with the U.S. Civil Rights movement:

What gets lost in popular accounts of the civil rights movement is the meticulous and lengthy organizing work sustained over a long period that was essential for every protest action. The movement’s success required myriad tactical shifts to survive repression and take advantage of opportunities created as the political landscape changed during the decade.

In Tufekci’s telling, the March on Washington was the culmination of years of institution building, in stark contrast to more sudden uprisings like Occupy Wall Street:

In the networked era, a large, organized march or protest should not be seen as the chief outcome of previous capacity building by a movement; rather, it should be looked at as the initial moment of the movement’s bursting onto the scene, but only the first stage in a potentially long journey. The civil rights movement may have reached a peak in the March on Washington in 1963, but the Occupy movement arguably began with the occupation of Zuccotti Park in 2011.

It’s interesting to reflect on the Occupy movement in light of the Gamestop episode two weeks ago; on one hand, you could squint and draw a line from Zuccotti Park to /r/WallStreetBets, but the only thread that actually exists is expressions of anger, at least from some number of Redditors, with Wall Street and its roll in the 2008 financial crisis and the recession that followed. There was certainly no organizational building in the meantime that culminated in taking on the shorts (and, unsurprisingly, enriching others on Wall Street along the way).

What actually happened — to the extent anything meaningful happened at all — is that instead of storming the barricades of Wall Street i.e. living in a tent two blocks away from a building long since removed from actual trading, /r/WallStreetBets used the system against itself. They didn’t protest short sellers; they took the other side of the bet.

The Meme Stock

Who, though, is “they”? Sure, there was /u/DeepFuckingValue, who according to a profile in the Wall Street Journal started buying GameStop stock in 2019, and making YouTube videos to promote his comeback thesis last summer. There was also /u/Jeffamazon, who made the case on Reddit that GameStop was primed for a short squeeze last fall. There were all of those folks who wanted to get back at Wall Street, and those that simply wanted to make a buck. There was Twitter, and CNBC, and there were hedge funds themselves.

This is why everyone has a story about what happened with GameStop, and why they are all true. The 2019 story was correct, but so was the summer 2020 story, and the fall 2020 story, and the January 2021 story. None of those stories, though, existed in isolation: they built on the stories that came before, duplicating and mutating them along the way. This is my second mistake: it turns out the Internet isn’t a cheap printing press; it’s a photocopier, albeit one that is prone to distorting every nth copy.

Go back to the time before the printing press: while a limited number of texts were laboriously preserved by monks copying by hand, the vast majority of information transfer was verbal; this left room for information to evolve over time, but that evolution and its impact was limited by just how long it took to spread. The printing press, on the other hand, by necessity froze information so that it could be captured and conveyed.

This is obviously a gross simplification, but it is a simplification that was reflected in civilization in Europe in particular: local evolution and low conveyence of knowledge with overarching truths aligns to a world of city-states governed by the Catholic Church; printing books, meanwhile, gives an economic impetus to both unifying languages and a new kind of gatekeeper, aligning to a world of nation-states governed by the nobility.

The Internet, meanwhile, isn’t just about demand — my first mistake — nor is it just about supply — my second mistake. It’s about both happening at the same time, and feeding off of each other. It turns out that the literal meaning of “going viral” was, in fact, more accurate than its initial meaning of having an article or image or video spread far-and-wide. An actual virus mutates as it spreads, much as how over time the initial article or image or video that goes viral becomes nearly unrecognizable; it is now a meme.

This is why, in the end, the best way to describe what happened to Gamestop is that it was a meme: it’s meaning was anything, and everything, evolving like oral traditions of old, but doing so at the speed of light. The real world impact, though, was very real, at least for those that made and/or lost money on Wall Street. That’s the thing with memes: on their own they are fleeting; like a virus, they primarily have an impact if they infiltrate and take over infrastructure that already exists.

The Meme President

In 2016 the Washington Post documented how 4chan reacted to Donald Trump being elected president:

4chan’s /pol/ boards have, for much of the 2016 campaign, felt like an alternate reality, one where a Donald Trump presidency was not only possible but inevitable. At some point Tuesday evening, the board’s Trump-loving, racist memers began to realize that they were actually right. “I’m f—— trembling out of excitement brahs,” one 4channer wrote Tuesday night, adding a very excited Pepe the Frog drawing. “We actually elected a meme as president.”

Trump, with his calls for protectionism and opposition to immigration, was compared throughout the campaign to previous presidential candidates like Ross Perot and Pat Buchanan; the reason why Trump was successful, though, was because he managed to infiltrate and take over infrastructure — the Repuclican Party — that already existed.

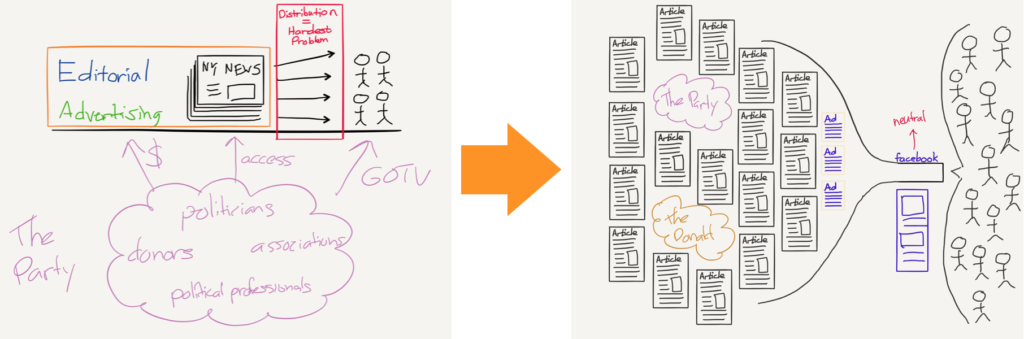

I wrote about this process in 2016 in The Voters Decide; it turned out that Party power was rooted in the power of the media over the spread of information. Once the media lost its gatekeeper status, however, the parties lost their mechanisms of control:

There is no one dominant force when it comes to the dispersal of political information, and that includes the parties described in the previous section. Remember, in a Facebook world, information suppliers are modularized and commoditized as most people get their news from their feed. This has two implications:

- All news sources are competing on an equal footing; those controlled or bought by a party are not inherently privileged

- The likelihood any particular message will “break out” is based not on who is propagating said message but on how many users are receptive to hearing it. The power has shifted from the supply side to the demand side

This is a big problem for the parties as described in The Party Decides. Remember, in Noel and company’s description party actors care more about their policy preferences than they do voter preferences, but in an aggregated world it is voters aka users who decide which issues get traction and which don’t. And, by extension, the most successful politicians in an aggregated world are not those who serve the party but rather those who tell voters what they most want to hear.

But what did Republican voters want? There were and have been any number of theories put forth, but I suspect the “truth” is similar to GameStop: all of the theories are true. After all, primary voters were electing a meme, and that meme, having infiltrated and taken over infrastructure that already existed, took over the Presidency.

Not that this is exclusively a right wing phenomonan; Portuguese politician and author Bruno Maçães wrote in History Has Begun in a chapter about the emergence of socialism in America:

Like all quests, the Green New Deal is set in a kind of dreamland, which allows its authors to increase the dramatic elements of struggle and conflict, but at the obvious cost of divorcing themselves from social and historical reality. The detailed consideration of technological and economic forces, for example, is ignored. The causal nexus between problem and solution appears fanciful. Since the authors of the Green New Deal have invented the story, they alone know the logic of events. There are perplexing elements in this logic. Why, for example, would one want to rebuild every building in America in order to increase energy efficiency when we are getting all our energy from zero-emission sources anyway? But a dream world follows different rules from those we know from the real one, which only increases its powers of attraction…

In an interview for the podcast Pod Save America in August 2019, Ocasio-Cortez explained the foundations of her political philosophy: “We have to become master storytellers. Everyone in public service needs to be a master storyteller. My advice is to make arguments with your five senses and not five facts. Use facts as supporting evidence, but we need to show we are having the same human experience. You have to tell the story of me, us, and now. The America we had even under Obama is gone. That is the nature of time. We have to tell the story of the crossroads.”

Millennial socialism sees history as a struggle to control the memes of production.

In Maçães’s telling, this is not a weakness, but a strength; that Joe Biden could simultaneously embrace the Green New Deal on his campaign website while insisting he didn’t support it in a debate is due to the fact that a meme can be whatever you want it to be.

The Meme Master

Last Monday, in an appearance on Clubhouse, Elon Musk was asked about memes:

It is safe to say that you might be the master of the memes, and in fact you had a quote that “Who controls the memes controls the universe.” Can you just explain what you meant by that?

EM: It’s a play on words from Dune, “Who controls the spice controls the universe”, and if memes are spice then it’s memes. I mean there’s a little bit of truth to it in that what is it that influences the zeitgeist? How do things become interesting to people? Memes are actually kind of a complex form of communication. Like a picture says a thousand words, and maybe a meme says ten thousand words. It’s a complex picture with a bunch of meaning in it and it can be aspirationally funny. I don’t know, I love memes, I think they can be very insightful, and you know throughout history, symbolism in general has powerfully affected people.

Musk’s point about the relevant power of memes to pictures makes perfect sense; what is notable is that the unit of measurement — words — are so clearly insufficient for the reasons I just documented. The power of memes is not simply the amount of information they convey, but the malleability with which they convey it. They have shades of Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, in that the very meaning of a meme is altered based on where it is encountered, and from whom. It’s meaning can be anything, and everything.

That, though, is why mastering memes is so powerful. Wired described quantum computing like this:

Instead of bits, quantum computers use qubits. Rather than just being on or off, qubits can also be in what’s called ‘superposition’ — where they’re both on and off at the same time, or somewhere on a spectrum between the two.

Take a coin. If you flip it, it can either be heads or tails. But if you spin it — it’s got a chance of landing on heads, and a chance of landing on tails. Until you measure it, by stopping the coin, it can be either. Superposition is like a spinning coin, and it’s one of the things that makes quantum computers so powerful. A qubit allows for uncertainty.

That sounds a lot like how I have described memes, which means to master memes is to stop the coin on your terms, and there is no better example of what this means than Tesla. I wrote one Weekly Article about Tesla, 2016’s It’s a Tesla, and I think it holds up pretty well. This is the key paragraph:

The real payoff of Musk’s “Master Plan” is the fact that Tesla means something: yes, it stands for sustainability and caring for the environment, but more important is that Tesla also means amazing performance and Silicon Valley cool. To be sure, Tesla’s focus on the high end has helped them move down the cost curve, but it was Musk’s insistence on making “An electric car without compromises” that ultimately led to 276,000 people reserving a Model 3, many without even seeing the car: after all, it’s a Tesla.

Later in that article I compared Tesla to Apple, its only rival as far as brand is concerned:

To that end, the significance of electric to Tesla is that the radical rethinking of a car made possible by a new drivetrain gave Tesla the opportunity to make the best car: there was a clean slate. More than that, Tesla’s lack of car-making experience was actually an advantage: the company’s mission, internal incentives, and bottom line were all dependent on getting electric right.

Again the iPhone is a useful comparison: people contend that Microsoft lost mobile to Apple, but the reality is that smartphones required a radical rethinking of the general purpose computer: there was a clean slate. More than that, Microsoft was fundamentally handicapped by the fact Windows was so successful on PCs: the company could never align their mission, incentives, and bottom line like Apple could.

This comparison works as far as it goes, but it doesn’t tell the entire story: after all, Apple’s brand was derived from decades building products, which had made it the most profitable company in the world. Tesla, meanwhile, always seemed to be weeks from going bankrupt, at least until it issued ever more stock, strengthening the conviction of Tesla skeptics and shorts.

That, though, was the crazy thing: you would think that issuing stock would lead to Tesla’s stock price slumping; after all, existing shares were being diluted. Time after time, though, Tesla announcements about stock issuances would lead to the stock going up. It didn’t make any sense, at least if you thought about the stock as representing a company.

It turned out, though, that TSLA was itself a meme, one about a car company, but also sustainability, and most of all, about Elon Musk himself. Issuing more stock was not diluting existing shareholders; it was extending the opportunity to propagate the TSLA meme to that many more people, and while Musk’s haters multiplied, so did his fans. The Internet, after all, is about abundance, not scarcity. The end result is that instead of infrastructure leading to a movement, a movement, via the stock market, funded the building out of infrastructure.

Memes and the Future

This is not, to be very clear, analysis about Tesla the business. The reason I only ever wrote one Article about Tesla and a handful of Daily Updates is because I was confused about the divorce between the company’s real world fortunes and its stock price. That confusion — like the weirdness about a company focused on sustainability buying Bitcoin — still exists!

Now, though, I realize that this confusion stems from making the same mistake I did in that old analysis of Facebook: I was looking to real world as a guide to understanding the Internet, when it was in fact inevitable that the Internet would, over time, come to impact the real world. Some of that impact will be fleeting, like many of the protests Tufekci documented; some will have short term effects, particularly in places, like Wall Street, that easily translate sentiment into prices. The biggest impact, at least for the next few years, will likely come from memes capturing existing infrastructure, like Trump did the Republican party, and Ocasio-Cortez, to a lesser extent, the Democratic party. The most intriguing people, though, both for the potential upside and the potential downside, are those that leverage memes to build something new.

- This article was actually written a few months before I coined the term Aggregation Theory, but it was clearly top of mind in that time period

- This, by the way, is actually a much more accurate manifestation of Metcalfe’s Law, which is about potential contacts in a network, not actual contacts; a long-standing criticism of using Metcalfe’s Law to describe social networks is that the attractiveness of most social networks is a function of how many people you know that are on the network, not how many you might know. That is why, for example, LINE is a much more valuable chat app for me in Taiwan than is WeChat, even though WeChat has vastly more users; more people I know are on LINE. TikTok, though, surfaces content from anyone, which is to say its value hews much more closely to Metcalfe’s Law.

文章版权归原作者所有。