App Store Arguments

Arguments in Epic Games, Inc. v. Apple Inc. wrapped up yesterday; Judge Yvonne Gonzales Rogers noted she had thousands of documents to pore over, but hoped to issue a decision within the next few months. I think there is a strong chance that Apple prevails, for reasons I’ll explain below, but that doesn’t mean the trial has been waste of time: it has cast into stark relief the different arguments that pertain to the App Store, and not all of them have to do with the law.

The Legal Argument

Apple came into the trial with a strong hand rooted in Supreme Court precedent.1

First, while it is possible to define the App Store for iPhones as a distinct aftermarket (see Kodak v. Image Technical Services), appellate courts have significantly narrowed that decision to limit its application to situations where the company selling the product that leads to an aftermarket is only barred from changing the rules after-the-fact to foreclose competition in the aftermarket; if the rules foreclosing competition are consistent, however, then there is no harm, because customers know what they are getting into. In the case of the iPhone, this means that Apple can control the market for iPhone apps, because customers already know that Apple controls the App market; if they don’t like it they can buy a different phone. This is why Apple spent time in the trial establishing that its control of the App Store was in fact a selling point of the iPhone, and a reason why customers chose to enter iOS’s more restrictive ecosystem.

Second, Apple also made the case that there is a competitive market for developers. This was an especially effective line of reasoning with regard to Fortnite, which makes more money from other platforms than it does from iOS; moreover, those platforms have rules that are similar to iOS, including exclusive payment platforms, no-steering provisions, and 30% commissions.

The most important case for Apple’s defense, though, is 2004’s Verizon v. Trinko, which established and/or reiterated several important precedents that support Apple’s position, even if Apple were held to be a monopolist.

First, a monopolist has a right to monetize its intellectual property; the opinion states:

The mere possession of monopoly power, and the concomitant charging of monopoly prices, is not only not unlawful; it is an important element of the free-market system. The opportunity to charge monopoly prices — at least for a short period — is what attracts “business acumen” in the first place; it induces risk taking that produces innovation and economic growth. To safeguard the incentive to innovate, the possession of monopoly power will not be found unlawful unless it is accompanied by an element of anticompetitive conduct.

This is why CEO Tim Cook in his testimony kept insisting that Apple had a right to monetize its intellectual property, and why the company has emphasized the cost of not simply running the App Store but also in developing APIs and developer tooling.2

Second, a monopolist has no duty to deal with any other company; the opinion states:

Firms may acquire monopoly power by establishing an infrastructure that renders them uniquely suited to serve their customers. Compelling such firms to share the source of their advantage is in some tension with the underlying purpose of antitrust law, since it may lessen the incentive for the monopolist, the rival, or both to invest in those economically beneficial facilities. Enforced sharing also requires antitrust courts to act as central planners, identifying the proper price, quantity, and other terms of dealing — a role for which they are ill suited. Moreover, compelling negotiation between competitors may facilitate the supreme evil of antitrust: collusion. Thus, as a general matter, the Sherman Act “does not restrict the long recognized right of [a] trader or manufacturer engaged in an entirely private business, freely to exercise his own independent discretion as to parties with whom he will deal.”

What this means for this case is that Apple has no duty to provide access to those APIs and development tools to companies that do not abide by its terms. There is a very limited exception to this provision (see Aspen Skiing v. Aspen Highlands Skiing), but like Kodak, it only applies to situations where the monopolist changes the rules; Epic, on the other hand, has always operated under the same set of in-app purchase rules.3

Third, the Court stressed that judges should carefully weigh the costs of enforcement with the benefits of an injunction:

Against the slight benefits of antitrust intervention here, we must weigh a realistic assessment of its costs. Under the best of circumstances, applying the requirements of §2 “can be difficult” because “the means of illicit exclusion, like the means of legitimate competition, are myriad”…Mistaken inferences and the resulting false condemnations “are especially costly, because they chill the very conduct the antitrust laws are designed to protect.” The cost of false positives counsels against an undue expansion of §2 liability. One false-positive risk is that an incumbent LEC’s failure to provide a service with sufficient alacrity might have nothing to do with exclusion. Allegations of violations of §251(c)(3) duties are difficult for antitrust courts to evaluate, not only because they are highly technical, but also because they are likely to be extremely numerous, given the incessant, complex, and constantly changing interaction of competitive and incumbent LECs implementing the sharing and interconnection obligations. Amici States have filed a brief asserting that competitive LECs are threatened with “death by a thousand cuts,” the identification of which would surely be a daunting task for a generalist antitrust court. Judicial oversight under the Sherman Act would seem destined to distort investment and lead to a new layer of interminable litigation, atop the variety of litigation routes already available to and actively pursued by competitive

LECs.

All of that mumbo-jumbo in the second part of that paragraph is referring to the specifics of the 1996 Communications Act and the complexities of Verizon’s obligations as a local exchange carrier (LEC). In another sense, though, the mumbo-jumbo is the point: the Court’s argument is that judges are ill-equipped to understand technical specifics and weigh important trade-offs, particularly absent any egregious anti-competitive behavior (as defined by the Court).

The Pragmatic Argument

This matters because the reality is that the App Store is complicated. One of the arguments that Epic raised in the case is that there are scams in the App Store; Epic’s argument is that effectiveness-at-rooting-out-scams should be a plane of competition, while Apple pushed out a post arguing that the App Store in fact stopped many more scams than it allowed, and that the fact there is only one way to get apps on your phone is a feature, not a bug.

As John Gruber noted, the sudden appearance of this post suggested that Apple felt it was losing the PR war:

There’s nothing curious about the timing of this post — it’s in response to some embarrassing stories about fraud apps in the App Store, revealed through discovery in the Epic v. Apple trial, and through the news in recent weeks. The fact that Apple would post this now is pretty telling — to me at least — about how they see the trial going. I think Apple clearly sees itself on solid ground legally, and their biggest concern is this relatively minor public relations issue around scam apps continuing to slip through the App Store reviewing process.

Another reason to think this is true is that I actually think that Apple underplayed their case: there are a whole category of transactions that are not explicit scams of the types documented in that post, but which are clearly designed to remove customers from their money as efficiently as possible. Now Apple’s incentives here are not pure: the company does make 30% of these purchases. But Epic is compromised as well, particularly once you realize that most of these problematic apps are games.

I’m not, to be clear, arguing that Fortnite is a problem; I’m sure Epic would be the first to say that they have a reputation to uphold — as, of course, would Apple. Not all developers, though, would be so scrupulous, and a world where any app could collect credit card information directly is one where it seems more likely than not that consumers will find themselves losing much more money than they anticipated, with no obvious recourse to get it back or make it stop.

This is where the malware discussion in the trial was relevant; Apple argued that iOS had less of it, while Epic attributed that to iOS’s sandbox architecture that keeps apps isolated from each other. The other malware takeaway, though, is the fact that it massively suppressed the market for third-party applications on Windows. Consumers didn’t suddenly get smart about apps, thanks to the pressure of competition; they simply stopped downloading and installing apps at all. One of the great triumphs of the App Store is the fact that it made consumers feel safe and secure about installing apps, dramatically expanding the market for developers — including Epic.

At the same time, there is a practical cost to Apple’s approach: there are entire classes of apps that for all practical purposes can’t exist on the iPhone, particularly those that entail paying licensing fees to 3rd parties on a percentage-of-total-sales basis. Apple, in one of the more damning emails to emerge over the last year, admitted as such:

This does, I would note, put Apple’s antitrust conviction in the ebooks case in considerably more dubious light: Apple was trying to shift the industry away from a wholesale model to an agency model, which is the exact sort of model that doesn’t work with the App Store. That the company was offering its own alternative — iBooks — makes it worse, just as the introduction of Apple Music made the application of App Store rules to Spotify particularly problematic.

What is also worth acknowledging, though, are the kinds of businesses that never get off the ground. During the pandemic, for example, Apple originally sought to take a cut of person-to-person businesses like counselors and trainers; the company did change the rules to allow one-to-one interactions to be paid for via an alternative payment method, but still demands a cut of one-to-many offerings like classes. There is also the impact on the burgeoning creator economy; I tweeted over the weekend:

In this world you don’t need 1,000 true fans to make a living; you need 1,786 — 536 fans to pay Apple, 253 fans to pay Twitter, and only then the 1,000 that make it possible to create something new. It is inevitable that some number of businesses never get started, because of this deadweight loss.

The Duopoly Argument

That tweet, I will admit, wasn’t entirely fair. While I noted that Twitter earned its cut by creating a market where one did not previously exist, the same argument can absolutely be made about Apple. As I noted above, Apple not only created the iPhone, it also created a willingness to download and experiment and pay that vastly expanded the market for developers. If Twitter deserves a cut, why not Apple? But then again, how far does it go?

Where does the “made something previously impossible possible” chain of causation and entitlement end? With the phone? With carriers? With TSMC? Obviously Apple believes it ends with the iPhone, but it’s worth exploring why that isn’t simply a wish but a reality; after all, the carriers actually did take a share of all transactions on their networks 14 years ago. The company that changed the status quo was Apple; I explained How Apple Creates Leverage in 2014:

While Apple in 2006 (in the runup to the iPhone) was in a much stronger position than 2003, they were still much smaller ($60.6 billion market cap) than AT&T ($102.3 billion) or Verizon ($93.8 billion) on an individual basis, much less the carrier industry as a whole. More importantly, carriers weren’t facing a collective existential threat like piracy, which significantly increased their BATNA [Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement] relative to the music labels.

The music labels, though, benefitted from a relatively low elasticity of substitution: if I wanted one particular band that wasn’t on the iTunes Music Store, I wouldn’t be easily satisfied by the fact another band happened to be available. The carriers, on the other hand, largely offered the same service: voice, SMS, and data, all of which was interoperable. This increased elasticity of substitution gave Apple an opportunity to pursue a divide-and-conquer strategy: they just needed one carrier.

Apple reportedly started iPhone negotiations with Verizon, but it turned out that Verizon was already kicking AT&T’s (then Cingular’s) butt through aggressive investment and technology choices, resulting in increasing subscriber numbers largely at AT&T’s expense. Verizon saw no need to change their strategy, which included strong branding and total control over the experience on phones on their network. AT&T, meanwhile, was on the opposite side of the coin: they were losing, and that in turn had a significant effect on their BATNA – they were a lot more willing to compromise when it came to branding and the user experience, and so the iPhone launched on AT&T to Apple’s specifications.

That is when Apple’s user experience advantage and corresponding customer loyalty took over: for the first time ever customers were willing to endure the hassle and expense of changing phone carriers just so they could have access to a specific device. Over the next several years Verizon began to bleed customers to AT&T even though their service levels were not only better, but actually widening the gap thanks to the iPhone’s impact on AT&T. Four years after launch the iPhone did finally arrive on Verizon with the same lack of carrier branding and control over the user experience; in other words, Verizon eventually accepted the exact same deal they rejected in 2006 because the loyalty of Apple customers gave them no choice.

Apple followed the same playbook in country after country: insistence on total control (and over time, significant marketing investments and a guaranteed number of units sold) with a willingness to launch on second or third-place carriers if necessary. Probably the starkest example of the success of this strategy was in Japan. Softbank was in a distant third place in the Japanese market when they began selling the iPhone in 2008; finally after four years second-place KDDI added the iPhone, but only after Softbank had increased its subscriber base from 19 million to 30 million. NTT DoCoMo, long the dominant carrier and a pioneer in carrier-branded services finally caved last year after seeing its share of the market slide from 52% in 2008 to 46%.

Forgive the long excerpt, but the specifics of what happened between Apple and the carriers is essential to understanding what makes the App Store question so challenging. What is critical to note is that Apple was able to break the carrier’s hold on what happened on their networks because competition (1) existed at the carrier level and (2) occurred in multiple markets. That meant that Apple had a place to leverage its ability to make something better.

The App Store market, on the other hand, is a worldwide duopoly, which dramatically reduces the point of leverage for any one app. Suppose Twitter wanted to push back on Apple’s policies, and go exclusively to Android; that would entail giving up around 20% of the market worldwide, and about 50% of the market in the U.S. It’s simply not viable to do a divide-and-conquer approach when there are only two alternatives in a worldwide market. That is why Apple and Google mostly copy each other’s policies, comfortable in the knowledge that no one app really matters.

I suppose Twitter could make its own phone, just as Apple could have built its own phone carrier, but given the essentialness of an App ecosystem, the former is actually a far more intractable challenge than the latter. One app may not matter to an ecosystem, but as a collective nothing matters more.

The Moral Argument

This gets at the part of this case that is, to be perfectly honest, kind of infuriating. Back in 2009 Apple came up with a memorable campaign for the iPhone:

I admit it — the first tweet above was wrong. Apple absolutely did a tremendous amount for developers. It invented the iPhone, it brought the concept of an App Store to the mass market, and it has iterated on both. And yes, it spends a lot of money on APIs and developer tools.

What the company no longer admits, though, is that developers did a lot for Apple too. They made the iPhone far more powerful and useful than Apple ever would have on its own, they pushed the limits on performance so that customers had reasons to upgrade, and even when Android came along iPhone developers never abandoned the platform. Sure, they had good economic reasons for their actions, but that’s the point: Apple had good economic reasons for building out all of those APIs and developer tools as well.

Apple said as much when the App Store first launched; Steve Jobs said in 2008 that “Our purpose in the App Store is to add value to the iPhone”, even as he admitted that “the App Store is much larger than we ever imagined.” When Apple introduced the iPhone SDK Jobs had analogized the company’s 70/30 split to iTunes, but it was already clear a few months later that the opportunity was far larger than music.

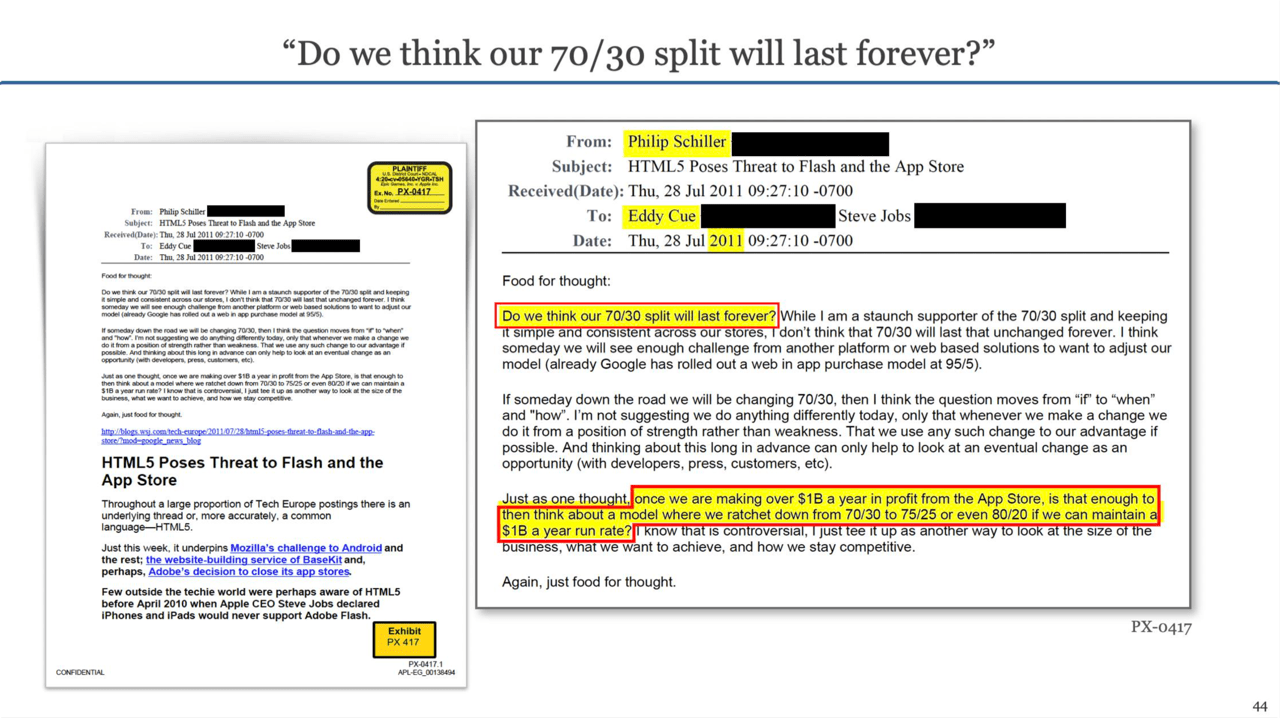

This worried longtime Apple executive Phil Schiller; in one of the most striking emails to emerge from the trial, he suggested that Apple might consider voluntarily capping its App Store profit to $1 billion, which was far more than the break-even amount Jobs hoped for at launch.

Schiller argued that Apple ought to make such a move from “a position of strength rather than weakness”; one can certainly make the argument that he was gravely mistaken, given that Apple makes somewhere in the neighborhood of $15 billion from the App Store, and that, for all of the reasons I just explained, is as secure in its competitive position as it has ever been.

And yet, it’s worth remembering that Apple did $294 billion in sales last year; the App Store is not and never will be its main business. Is it strong to continue to tarnish the customer experience with popular apps, its reputation with developers, and provoke criticism from Congress simply because it can? How much might it have been worth to remember that while Apple will always have the leverage with individual developers, developers as a collective — along with creators and authors and musicians and everyone else who wants to build a business on the iPhone — are exactly what makes the iPhone so compelling?

The Anti-Steering Argument

The argument that Judge Gonzales Rogers seemed the most interested in pursuing was one that Epic de-emphasized: Apple’s anti-steering provisions which prevent an app from telling a customer that they can go elsewhere to make a purchase. Apple’s argument, in this case presented by Cook, goes like this:

This analogy doesn’t work for all kinds of reasons; Apple’s ban is like Best Buy not allowing products in the store to have a website listed in the instruction manual that happens to sell the same products. In fact, as Nilay Patel noted, Apple does exactly this!

The point of this Article, though, is not necessarily to refute arguments, but rather to highlight them, and for me this was the most illuminating part of this case. The only way that this analogy makes sense is if Apple believes that it owns every app on the iPhone, or, to be more precise, that the iPhone is the store, and apps in the store can never leave.

Judge Gonzales Rogers, meanwhile, is not the only one that finds Apple’s entitlement to apps problematic; the European Commission specifically cited the App Store anti-steering provision in its Statement of Objections about Apple’s approach to competition “in the market for the distribution of music streaming apps through its App Store”. That position of strength is starting to weaken.

After the European Commission’s announcement, Benedict Evans wrote in Resetting the App Store:

We’ve been arguing about this for a decade, but now something is going to change, partly because of Epic’s lawsuit (which it might or might not win) but much more importantly because the EU has a whole set of competition investigations into the sandbox, the store and the payment system, and is highly unlikely to accept the status quo. When Apple launched the store in July 2008 it had only sold 6m iPhones ever, but now a billion people have one, and competition laws apply, whether you like it or not. Epic might lose, but Spotify will win. What will that mean, though? What rules will change, and how, and what will that mean for anyone who isn’t an Apple or Spotify shareholder?…

It’s possible to believe that the sandboxed App Store model has been a hugely good thing, and also that Apple has too often made the wrong decisions in running it, and also that unwinding those decisions while preserving the underlying model won’t actually change much for many companies or consumers, and won’t really be a significant structural change in how tech works.

What Evans highlights is that all of these arguments about the App Store are good ones. Apple has good ones, Epic has good ones, Spotify has good ones, the European Commission has good ones, and I’d like to think I have good ones as well. As the Supreme Court has noted, though, a realm with lots of complexity and lots of good arguments about every single trade-off is one that is extremely poorly suited to judicial oversight. Congress is certainly an option — there is a utility sort of argument to be made about the App Store — but that comes with massive risks, given the relative frequency of changes in the law relative to changes in technology (the Epic case is being argued under a law passed 121 years ago).

What I wish would happen — and yes, I know this is naive and stupid and probably fruitless — is that Apple would just give the slightest bit of ground. Yes, the company has the right to earn a profit from its IP, and yes, it created the market that developers want to take advantage of, and yes, the new generation of creators experimenting with new kinds of monetization only make sense in an iPhone world, but must Apple claim it all?

Let developers own their apps, including telling users about their websites, and let creatives build relationships with their fans instead of intermediating everything.4 And, for what it’s worth, continue controlling games: I do think the App Store is a safer model, particularly for kids, and the fact of the matter is that consoles have the same rules. The entire economy, though, is more than a game, and the real position of strength is unlocking the full potential of the iPhone ecosystem, instead of demanding every dime, deadweight loss be damned.

- Obvious caveat: I am not a lawyer, although I have consulted with both an antitrust lawyer and an antitrust economist about legal precedents surround the App Store; this is also about U.S. law only

- There is a question as to whether Apple’s approach is the least restrictive way to achieve legitimate business ends; this is a very difficult argument to win in court, though, as any proposed solution has to be better in all regards, including appropriately compensating the IP holder.

- Some “reader” apps like Kindle did have the rules changed on them — Apple used to let them link out to the web for payments — but that was years ago before the iPhone was as dominant as it is today; parental control apps may have a more compelling case.

- Customers, of course, could decline; that would be a reason for developers and creatives to opt into Apple’s model

文章版权归原作者所有。